Rome, the eternal city, is trending on TikTok. Fifteen and a half centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the abdication of the boy emperor Romulus Augustulus (476 AD), women are asking: ‘How often do men think about the Roman empire?’ The answer seems to be ‘frequently’. Various theories (often simplistic) have been advanced: that an interest in Rome is a safe space for macho fantasies (thank you, Mary Beard), or that it is linked to white supremacism.

But an interest in Rome is unsurprising. The decline and fall of the Roman Empire, as English author, historian, and politician Edward Gibbon remarked, was “a revolution which will ever be remembered, and is still felt by the nations of the earth”.

The stories of the emperors have thrilled, shocked, and inspired generations. Their laws were the basis for the legal systems of Europe and its colonies until the Napoleonic Code, and we still use a version of the Roman calendar today.

The Romans, as Monty Python pointed out, also gave us sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a fresh-water system, and public health. Not to mention inventing central heating, newspapers, concrete, stained glass, medical instruments, and an efficient postal service.

Even today, the French and Italians still think of Rome every time they relieve themselves: urinals are named after Vespasian (r. 69–79), who taxed public lavatories. “Does this money stink?” he asked his son, waving a coin under his noise. “And yet it comes from urine!”

For my part, I have been fascinated with Rome since my youth, when I went on a school trip to the German city of Trier – or, as the Romans knew it, Augusta Treverorum, one of four capital cities of the later empire. (Karl Marx was born there, too, somewhat later.)

Do I often think about the Roman Empire? Every day. I’ve devoured ancient histories and modern biographies (the ANU had a rather wonderful collection, dating back to the turn of the century); wandered museums, greeting busts of Roman emperors as old friends; and carry a few replica coins in my wallet. (The genuine ones are at home.)

I can list the emperors in order chronological, from Augustus to the third century crisis and the tetrarchy, when it all becomes rather confusing. (C’est à faire perdre son latin, as the French say: it’s enough to make one forget one’s Latin.) I even tried my hand at a short play about the assassination of Domitian, performed a decade or so ago. Besides, who isn’t fascinated by history? The colour and drama of the past capture my imagination.

The Roman emperors are a gallery of psychological portraits – as Gore Vidal observed, Suetonius’s Twelve Cæsars shows what people will do when given absolute power. Here are the best of men (paragons of goodness like Antoninus Pius [r. 138–61], for instance) and the worst (monsters like Caligula [r. 37–41]), with every shade in between: playboys and politicians, visionaries and halfwits, geriatrics and children, and eight-foot-tall ogres.

“In the conduct of those monarchs,” Gibbon declared, “we may trace the utmost lines of vice and virtue: the most exalted perfection and the meanest degeneracy of our own species.”

What were they like? So much of Roman history was written by senators, who resented the end of the republic, or were propagandists for the next régime. Was Domitian (r. 81–96) a tyrant with a penchant for darkened rooms and stabbing flies, or one of Rome’s ablest administrators? Would his brother Titus (r. 79–81), “the darling of the people”, have been so favourably remembered had he reigned longer than two years? People had feared he would be another Nero.

Would the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–80) have been a better leader had he disposed of his son, Commodus (r. 180–92), of Gladiator infamy, under whose reign Rome’s slow path to decline began? (“Our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust,” Gibbon remarked.)

We revise our opinions of the emperors: the teenage Elagabalus (r. 218–22), once considered Rome’s most depraved emperor, his name stinking like the sewer into which his body was flung, has been reassessed as a gay icon and transgender martyr.

Here, too, are terrible crimes: Nero (r. 54–68), who, like Œdipus, slept with his own mother, then, like Orestes, murdered her; or Fausta, the wife of Constantine (r. 272–337), a second Phaedra, consumed with a destructive passion for her stepson.

Here are love stories that echo down the ages: Antony and Cleopatra at the fall of the Republic, or Hadrian (r. 117–38) and the youth Antinous, who drowned (suspiciously?) in the Nile.

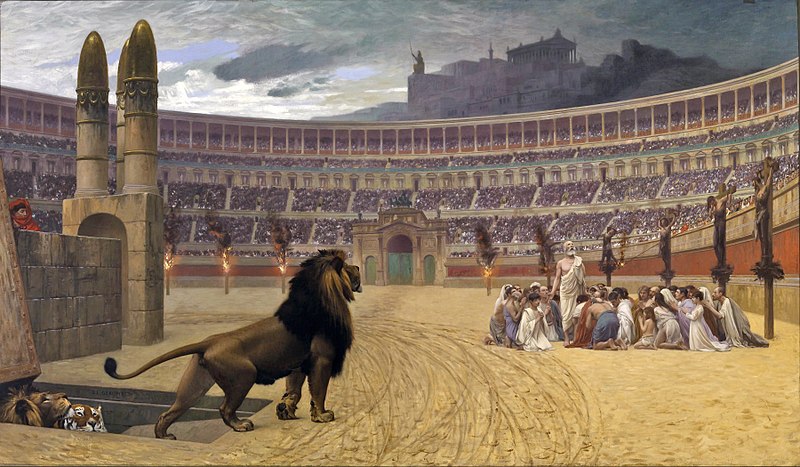

Here is comedy, too: A merchant had sold paste to the emperor Gallienus’s wife, claiming they were real jewels; the empress demanded he be punished. Gallienus (r. 253–68), pausing from 15 years of battles to restore the empire during the height of the third century crisis, sentenced the swindler to be eaten by a lion in the arena. Instead of the slavering beast the criminal expected – out of the holding cage strutted a chicken. “He committed a deception, and has been punished with one,” the emperor said, laughing. (History doesn’t record whether the swindler ended up with egg on his face.)

Speaking of chickens, the useless emperor Honorius (r. 395–423) was more concerned with his pet rooster than with the sack of Rome in 410. According to Procopius: “At that time they say that the Emperor Honorius in Ravenna received the message from one of the eunuchs, evidently a keeper of the poultry, that Rome had perished. And he cried out and said, ‘And yet it has just eaten from my hands!’ For he had a very large rooster, Rome by name; and the eunuch comprehending his words said that it was the city of Rome which had perished at the hands of Alaric, and the emperor with a sigh of relief answered quickly: ‘But I, my good fellow, thought that my fowl Rome had perished.’ So great, they say, was the folly with which this emperor was possessed.” Honorius had executed the only general trying to rescue the situation.

Rome, too, was a far more cosmopolitan and liberal society than any appeal to machismo or white supremacism would suggest. It was a thriving, multi-ethnic society that endured for centuries, spreading from remote Britain and the Baltic Sea to the Sahara Desert and Iraq.

It was racially and (on the whole, the persecution of the Christians being much exaggerated) religiously tolerant. Citizenship was extended from Romans to everybody in the empire, while the imperial purple itself was worn by provincials – not just Europeans, but Africans, Syrians, and Arabians.

It was upwardly mobile, too; emperors included common soldiers, ex-mule drivers, and even the son of a freed slave.

Roman women enjoyed far more rights than in Ancient Athens, where they were largely confined to the house, kept in purdah. While Roman women were primarily mothers and caretakers, and subject to the authority of their male relatives, they could own property and run businesses, for instance.

While no women ruled in their own right (unlike in the later Byzantine Empire), some wielded political power through their families (like Livia, Agrippina II, or Julia Domna), or were cultured intellectuals (Julia Maesa, wife of Septimius Severus [r. 193–211], presided over a brilliant salon).

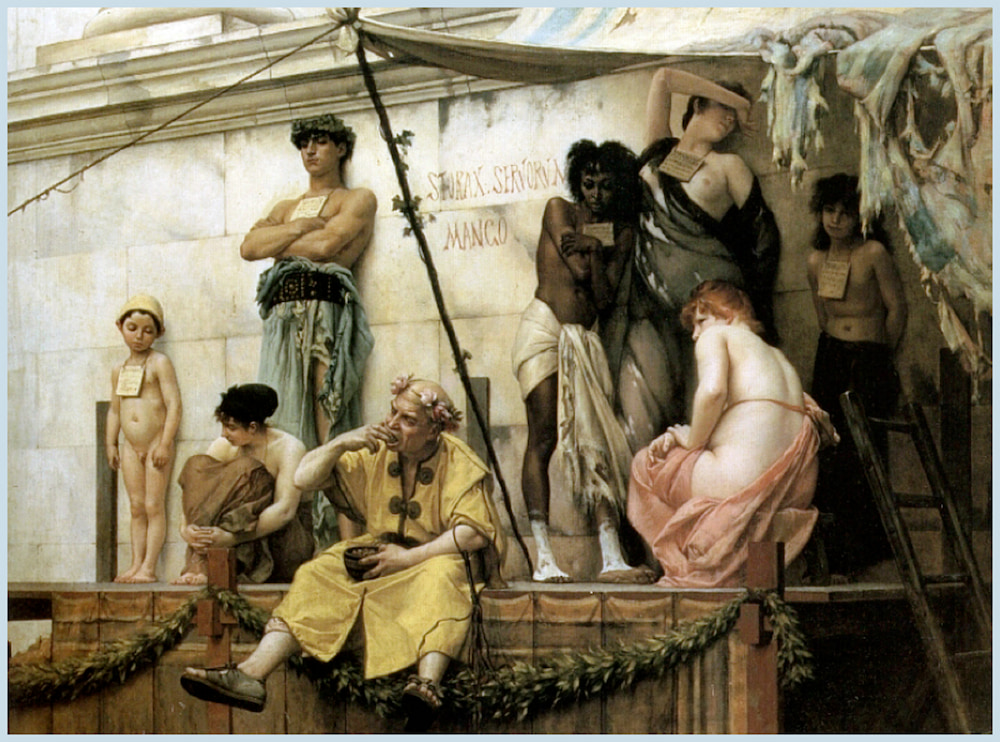

True, the Roman economy relied on slavery, as did much of the ancient world; but to be a slave in Rome was very different from the horror of the American South. While some were harshly treated, and worked in mines, many were household servants, teachers, secretaries, and skilled artisans.

Slaves had legal rights (they could enter into contracts, own property, seek legal redress, including against their masters, and it was illegal to kill slaves without justification). They could buy their freedom, or were freed by their former masters. Many freed slaves became wealthy and powerful, some even serving as government ministers.

The Roman Empire offers intriguing parallels with the present. Many commentators worry that demagogues and strongmen around the world seek to be Caesars, and that the United States itself, modelled on the Roman republic, might similarly become an autocracy. Donald Trump reminded them of Nero or Commodus: showmen, exhibitionists, populists, adored by the common people for cocking a snook at the establishment, loathed by the élite who considered them a disgrace to their nation. Likewise, Joe Biden has been compared to the absent-minded Claudius (r. 41-54), who stabilised the empire after Caligula; Vespasian, the victor of the civil wars after Nero; or the elderly, experienced politician Nerva (r. 96–98), the first of the “Five Good Emperors” after Domitian’s death.

Likewise, pundits believe Valens’s (r. 364–78) bungling of a refugee situation (admitting a host of Goths without integrating them into Roman society, and in fact mistreating them, leading within a few decades to the sacking of the city) might hold lessons for migrant policy in both America and Europe.

Identitarian zealots might be today’s successors to the parabalani, the Christian fanatics who smashed pagan statues and artefacts, and murdered the woman mathematician Hypatia.

Here in Australia, the disappointing prime ministership of Malcolm Turnbull, who had the potential to be a great statesman, reminded me of Tacitus’s famous tag about Galba (r. 68–69): Omnium consensu capax imperii, nisi imperasset (“He was universally seen as capable of ruling, had he never ruled” / “All would have agreed that he was worthy of the imperial office, if he had never held it”).

Rome’s history has inspired later generations, from theatre (the plays of Shakespeare and Racine, Ibsen and Camus), music (almost every second 18th century opera seria, several Belle Époque French operas, Nowowiejski’s oratorio Quo Vadis?, based on Sienkiewicz’s classic novel), and painting to the comic book adventures of Asterix the Gaul.

Novelists like Marguerite Yourcenar (the philosophical, introspective Memoirs of Hadrian, one of Rome’s most cultured and cosmopolitan rulers), Gore Vidal (Julian, about the last non-Christian emperor, r. 331–63), and Lion Feuchtwanger (the Josephus trilogy, about a Jewish historian’s attempts to find his place in Flavian Rome, after the sacking of the Temple of Jerusalem) have told the stories of Roman emperors and citizens with great penetration.

And, of course, Robert Graves’s magnificent I Claudius and Claudius the God, the vipers’ nest that was the Julio-Claudian dynasty described by one of their own, the overlooked, stammering historian and family fool who finds himself reluctantly crowned emperor. The BBC series is arguably the greatest television drama of all time: the brilliant script combines Suetonian scandalmongering with Shakespearean high camp, while the cast is a who’s who of British thespian talent. (ITV’s earlier Caesars may be even better: its production values are less polished, but the script is more political, sharper and more ambiguous.)

Rumour has it Caracalla (r. 211–17) will be the villain in Ridley Scott’s sequel to Gladiator. I am surprised he has not been made the star of a play or an opera; he would make a splendid subject for a drama. This “common enemy of mankind” (Gibbon) tried to kill his father, and stabbed his brother in his mother’s arms, and was reputedly haunted by their ghosts; believed himself the reincarnation of Alexander, and put Alexandria to the sword; murdered his bride and her family at their wedding, and chose lions for his bed-mates. The soldiers, recognising a kindred spirit, loved him – all but one, who slashed at him as he took a slash by the side of the road. The emperor died unrelieved, but the empire was much relieved. (But this is taking the proverbial.)

But one of the great tragedies is that so little Classical literature itself survives: somewhere between one and 10 per cent. The lost works include a third book by Homer; much of Greek theatre, from Agathon to Xenophon; works of science; histories and memoirs; and such uplifting works as Suetonius’s Lives of Famous Whores, Physical Defects of Mankind, and Greek Terms of Abuse.

But we are lucky to have a few Roman plays, novels, and poetry, as well as several important historical works – including that hallucinatory forgery, the Historia Augusta (which “contains much that is apocryphal, or at least wildly inaccurate”). We have the early sitcoms of Terence and Plautus, and the grim and bloody tragedies of Seneca, which centuries later gave rise to Marlowe and Shakespeare. We have parts of Petronius’s Satyricon, which inspired the 19th century Decadent movement and was filmed by Fellini. And in lighter vein, we have The Golden Ass of Lucius Apuleius, in which a young man makes an ass of himself until restored by the goddess Isis; it is a diverting account of his amorous misadventures and encounters with witches and brigands.

We also have an Ancient Roman cookbook, De re coquinaria, by the epicure Apicius. The popular image of Roman haute cuisine is orgies where gluttons gorge themselves on dormice and flamingo innards and camel heels, tickle their throats with peacock feathers, then rush off to use the vomitorium (which is, somewhat disappointingly, a corridor in an amphitheatre). It’s true that Vitellius (r. 69) concocted the ‘Shield of Minerva’, an enormous, extravagant, and emetic mixture of sow’s udders, the livers of pike, the brains of pheasants and peacocks, flamingo tongues, and the milt of moray eels.

But Roman cuisine is far more palatable. I have been cooking it for nearly 30 years. I first discovered it in the Zum Domstein restaurant at Trier, which served recipes based on Apicius. A year later, I found John Edwards’s adaptation for the modern kitchen at a school bookfair.

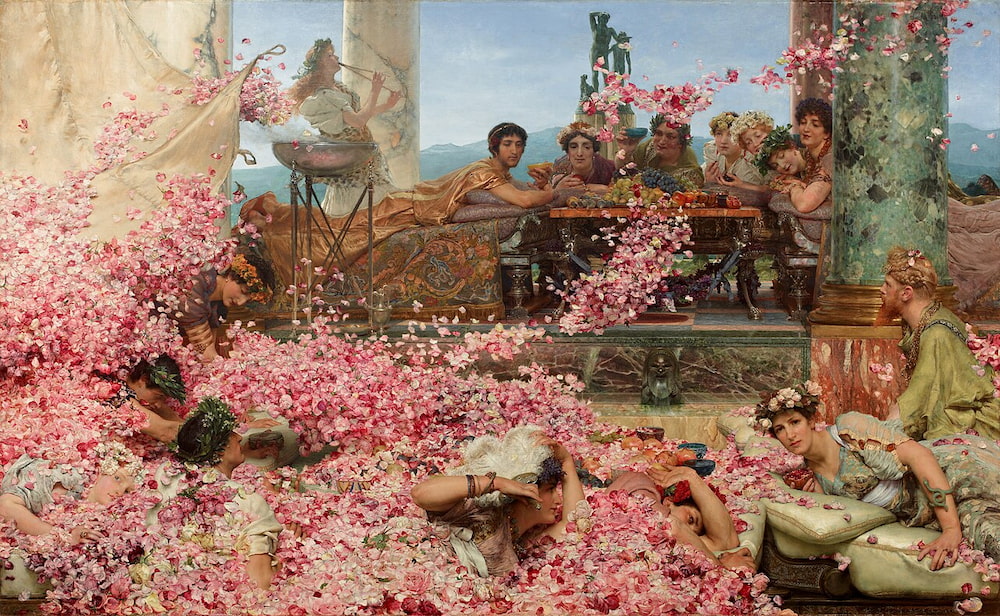

Roman food is almost sweet and sour; it uses wine, honey, spices (coriander, cumin, and celery seed), and a splash of fish sauce. I can recommend the likes of chicken Vardanus with chives and hazelnuts; veal in sweet and sour onion sauce, or fennel nut sauce; suckling pig stuffed with green beans; calf’s brains and egg dumplings; sweet omelettes; and honey and spice cakes. Certainly more appetising than Elagabalus’s banquets of wax food where lions and tigers roamed around the dinner tables and the guests were smothered with rose petals.

One question remains: If an infinite number of monkeys with an infinite number of typewriters would eventually produce the complete works of Shakespeare, how long would it take them to produce the works of Gibbon?