All children and young people in child protection effectively suffer PTSD, and First Nations children and young people are over-represented – but Rachel Stephen-Smith, ACT families and community services minister, hopes a new strategy to reform child and youth services will fix the problem.

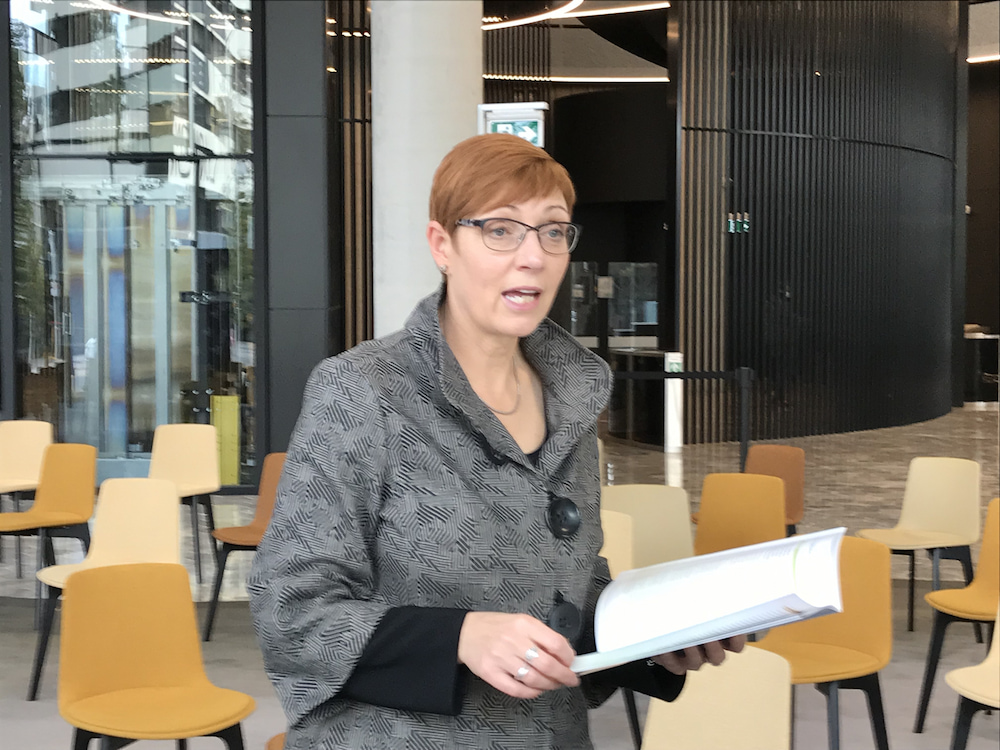

Next Steps for Our Kids 2022–30, launched yesterday, is “a huge milestone in the reform of child and family services in the ACT”, Ms Stephen-Smith said.

Those services will become more trauma informed and restorative, and support will be provided earlier so families can avoid reaching crisis and fewer children and young people will need to come into statutory care, she explained.

“Our vision is that all children and young people in the ACT are safe, strong, and connected and able to live their best lives,” Ms Stephen-Smith said. “That can only happen when the whole system works together.”

The ACT Council of Social Service (ACTCOSS) welcomed the release of the Next Steps, and acknowledged its prioritising of First Nations families.

“The strategy demonstrates the ACT Government’s commitment to improving trust and transparency and building a continuum of support for families in our communities,” Dr Emma Campbell, ACTCOSS’s CEO, said.

Next Steps builds on A Step Up for Our Kids 2015–20, which increased the number of children, young people, and families receiving family support services, and reduced the number of children entering out-of-home care. (According to government figures, 169 fewer children and younger people lived in out-of-home care, thanks to the program.)

The strategy will extend care for young people from the age of 18 to when they turn 21, making it an automatic entitlement, “without them needing to jump through hoops,” Ms Stephen-Smith said.

An excellent idea, Dr Campbell thinks. “Children are rarely independent at 18, and our systems must reflect that reality. The longer we can support young people, the more likely they are to continue their education, experience positive mental health, [and] avoid homelessness and engagement with the criminal justice system.”

The Children and Young People Act 2008 will be modernised to align with contemporary practice and support better information sharing. The government is reviewing the Act, to make child protection services’ decisions more transparent, Ms Stephen-Smith said.

New Charters of Rights will give parents, families, and carers the power to challenge the system when they feel their rights are not being upheld. A Ministerial Council that includes stakeholders and people with lived experience will guide government and create partnerships around reform.

“The fundamental commitment we’re making here is to work with children and young people, to work with families, to work with carers, and to work with our non-government partners,” Ms Stephen-Smith said. “We know that we have work to do to build trust, and to build a more transparent system…”

The strategy will implement recommendations of Our Booris, Our Way (2019), a wholly Aboriginal-led review of the child protection system: Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations and transition responsibility for case management; an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Young People Commissioner; and fully embedding the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle in legislation, policy, and practice.

The Principle, introduced in 1984, aims to reduce the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in child protection and out-of-home care systems.

But First Nations children in the ACT were 13 times more likely to be in out-of-home care than non-Indigenous children, and more than 30 per cent of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care are placed with non-Indigenous carers who are neither relatives nor kin, Rachelle Kelly-Church, head of the Gulanga Program, said. 29 per cent of children and young people on long-term orders in out-of-home care in the ACT are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, Ms Stephen-Smith stated.

“Clearly, that is absolutely unacceptable,” she said. “That is not OK, and we have a lot of work to do to turn that around.”

Under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, the ACT Government is committed to reducing the rate of over-representation by 45 per cent, the minister remarked.

Children and young people, whether First Nations or not, come into care because of untreated or undiagnosed mental health, drug and alcohol use by their parents, and domestic and family violence. Ms Stephen-Smith said. “Unfortunately, those things are also more prevalent in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

“So we have to work with those services and those communities to ensure that families are getting the support early, so they’re not even coming into contact with the statutory system – but when they do come into contact with the statutory system, that we have culturally safe services that can support them to figure out for themselves what their challenges are, and how they’re going to address them.”

Ms Kelly-Church believes these reforms are urgently needed.

“Addressing these serious system failures will require careful and ongoing consultation with Aboriginal communities in the ACT,” she said.

Dr Campbell thought the reforms were welcome, but long overdue. “In particular, the commitment to establishing internal and external review mechanisms was made some time ago, but we have yet to see them implemented and utilised.”

She called on the ACT Government to further its commitment to raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 14 by resourcing the service system reforms child protection expert Professor Morag McArthur recommended.

“The Next Steps for Our Kids strategy and principles it sets out are important,” Dr Campbell said. “It’s time to get on with the work of making our community safer and more supportive for all families, children, and young people.”