We pass it when we go to the zoo, some of us pass it every day on our way to work. But have you ever stopped to wonder what happens in the belly of the beast that is Scrivener Dam? CW recently went on a behind-the-scenes tour of the monument that controls Lake Burley Griffin’s water levels.

Earlier this week, Tuesday 6 September, members of both the federal and ACT governments met at Scrivener Dam Lookout to discuss the planned work for the structure. For nearly 60 years, the dam has been preventing flooding disasters across the capital and the federal government has committed $38.5 million to see that it will continue doing so for 60 more.

“We know over time we’ve got to look after the assets right across our community. And so, $38.5 million will go to anchor the dissipator here and make sure that for a long time to come that any spill doesn’t impact the land around it,” said Minister for Territories, Kristy McBain MP.

The minister also said it was an opportunity to mark a new era, one of collaboration between the two levels of government.

“We want to work with our state and territory counterparts and I’m here today to recommit that relationship. The ACT is an important partner for the federal government, and we look forward to working with them into the future.”

ACT Minister for Environment and Heritage, Mick Gentleman, welcomed the funding and the collaboration with the Commonwealth.

“It really is an important announcement for Canberra and Lake Burley Griffin and the important infrastructure we have here at Scrivener Dam to ensure we can keep it going for the next 100 years and longer after that, if need be.”

With the formalities out of the way, the tour was ready to start with our guide, David Wright from the National Capital Authority.

Before heading underground, Mr Wright explained why the funding was crucial for the future of the dam. After three years of studying how the structure reacted to certain conditions and flows, they found something concerning.

“Under certain conditions, there is a risk that the dissipator slab could start to be displaced. If it fails, the flows from the floodgate could undermine the foundation rock underneath the dam and cause it to fail. It’s not an imminent risk, the dam isn’t going to fall over, but there is a risk in the future it might.”

What is a dissipator and why is it important?

The dissipator is the area where the overflow water is released. As enormous amounts of water are released at neck-breaking speed, there needs to be a safeguard to absorb some of the energy to stop it from eroding the ground below.

Mr Wright says the term dissipator encompasses the whole downstream area; the concrete slab, the infill, the shoots that the water flows off and the dissipator blocks.

“They are all a structure which is designed to take the energy out as the water flows over. It will land on the shoot, so past the shoot blocks and into the dissipators and they’re what take most of the energy out.”

To ensure the structure remains sound, workers will be drilling and installing 700 new anchors into the foundation rock at a depth of 15 metres. The slab will be bulked up by another half metre and then everything will be raised.

Mr Wright says the design is expected to take around another 10 months, followed by two or three years for construction. The dam will remain functional during the upgrade; this will be done by staging the project to ensure things can still run smoothly.

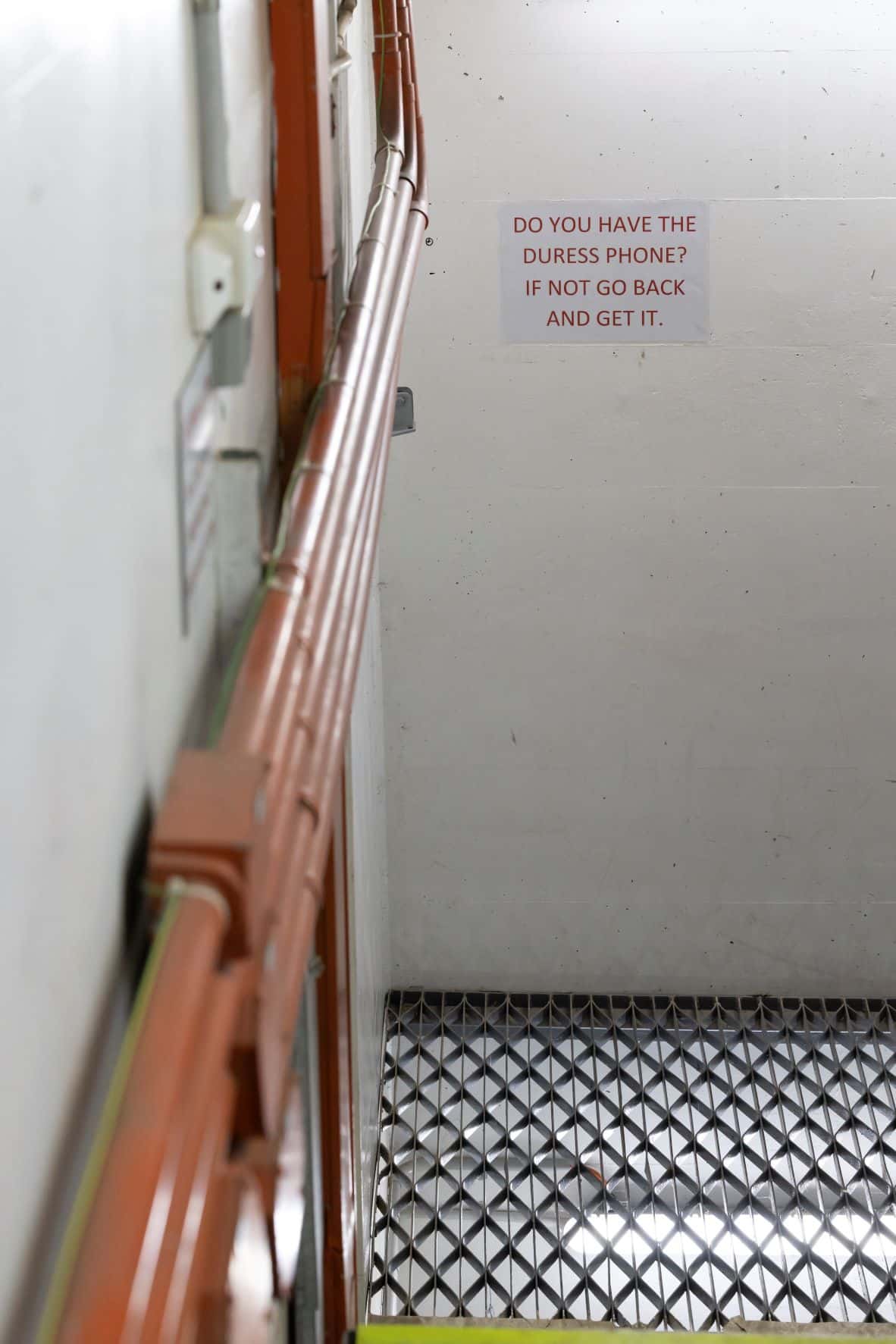

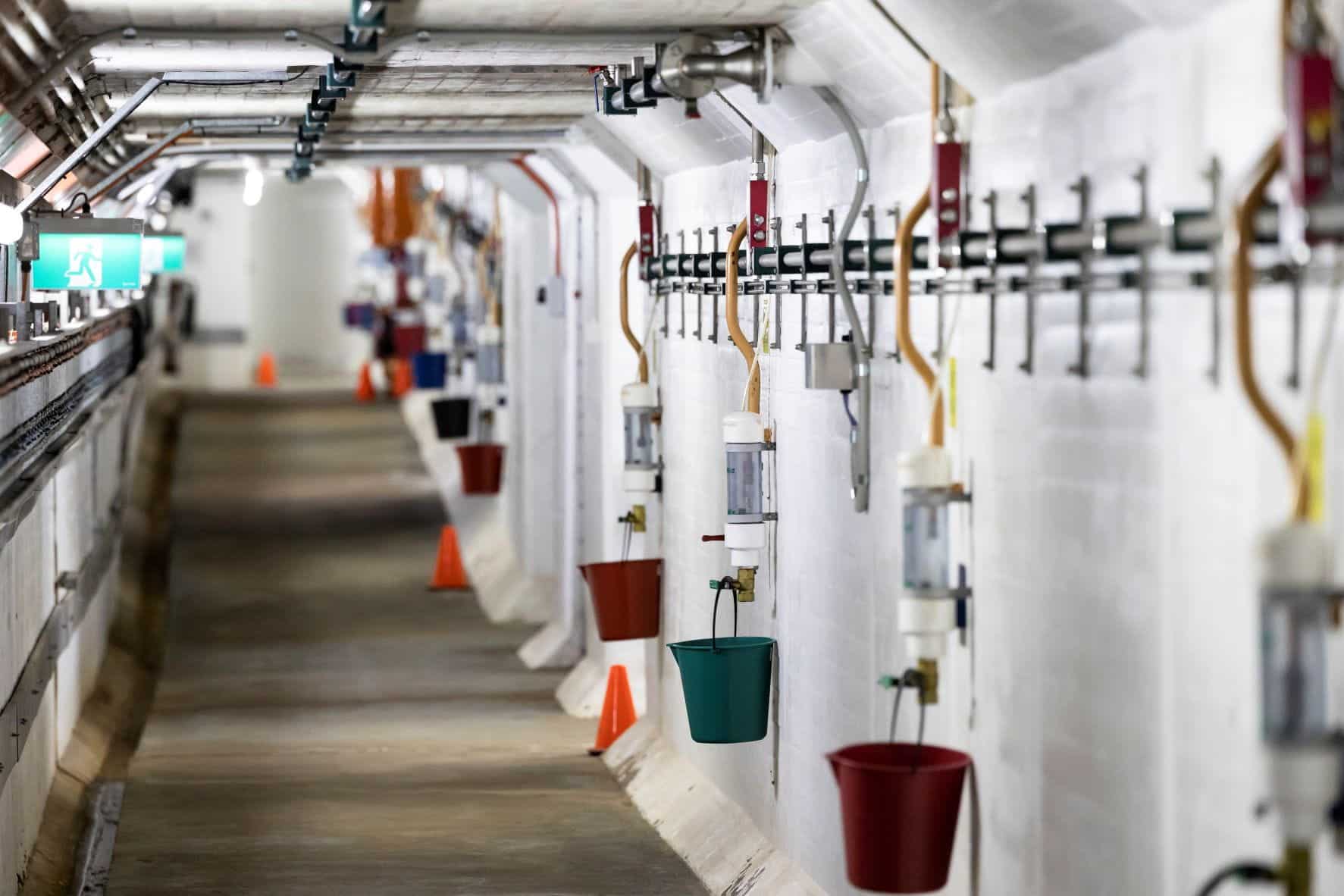

After descending a long spiral of stairs, you enter the seemingly never-ending concrete tunnel. Overhead, cars thump across the bridge while lions can be heard roaring at the zoo. Between these tunnels and the control room, the work is done to ensure Lake Burley Griffin remains at 555.95 metres above sea level, give or take 150mm.

“We have a very big catchment, it catches about 1,800 square kilometres and extends all through urban Canberra, past Queanbeyan and Googong. It also has a very big watershed; once it starts to rain, the catchment is really high flow.”

Today the dam can be managed electronically, however, when it was built, everything had to be run mechanically. There are remnants of these devices throughout the structure; Mr Wright explains how the ingenious float well worked as it stands proud, though no longer connected to its pulley system.

“The well fills with lake water and that’s got a float in it; as the lake level rises, the float level rises in the chamber and activates the pulley.”

Brightly coloured buckets hang in stark contrast to the industrial grey corridors. These are used to catch hydraulic fluid to prevent it from entering the waterways in the catchment.

“We could go down the track of getting something engineered and installed but quite often the simplest solution is the best and the buckets collect things effectively.”

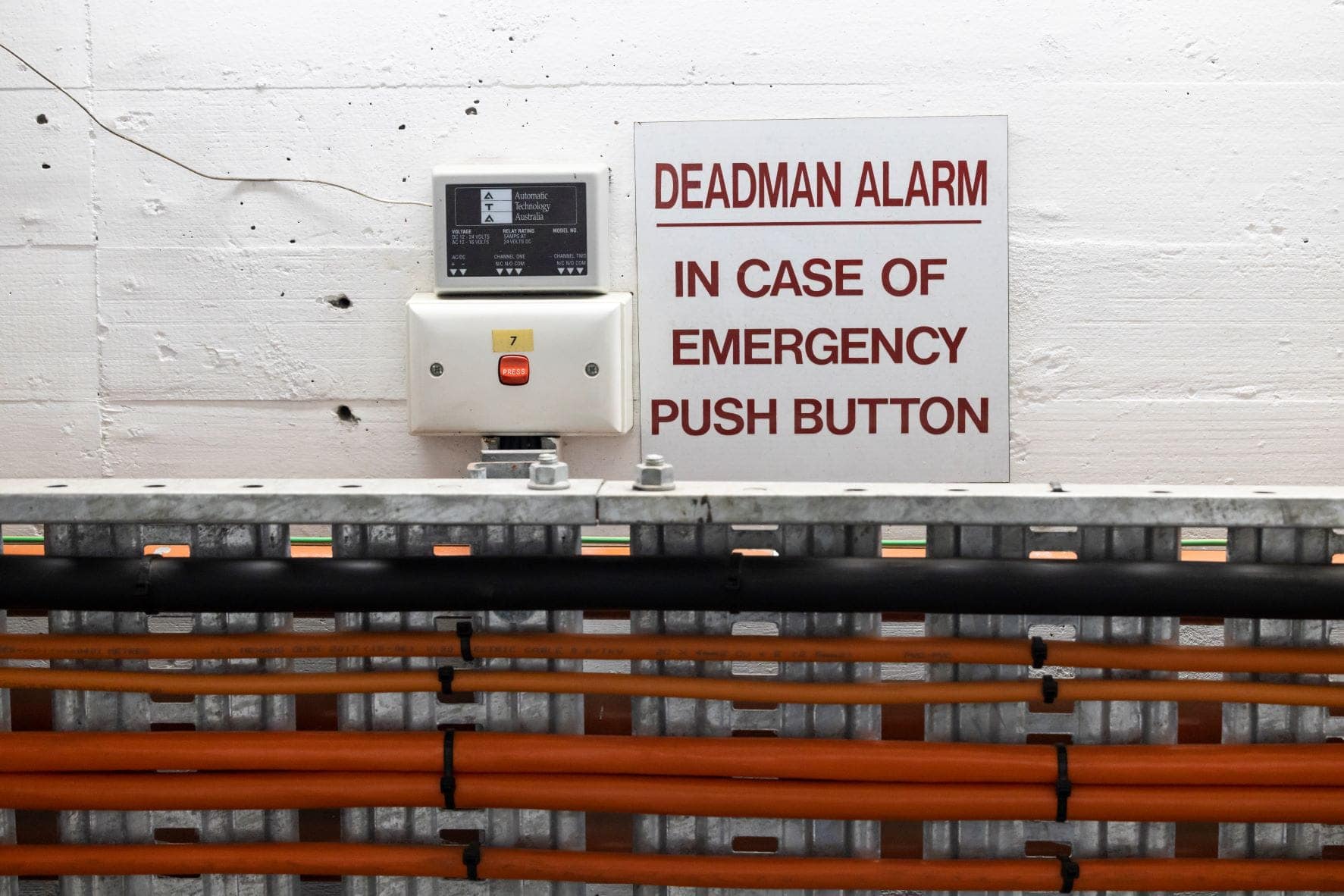

Mr Wright assures us the disconcertingly named ‘dead-man alarms’ are just regular emergency alarms with an unfortunate name.

“I think, technically, a dead-man alarm activates when you take the hand off the switch or something like that; it was just a term or phrase that was used at some point in time and has been retained.”

The dead-man system is used to monitor staff onboard a ship when they enter an area that is not usually manned, like the engine room; upon entering, the alarm in triggered and a countdown begins. If they don’t push the button before the countdown ends, an alarm is sounded to let members of the crew know he might be in distress.

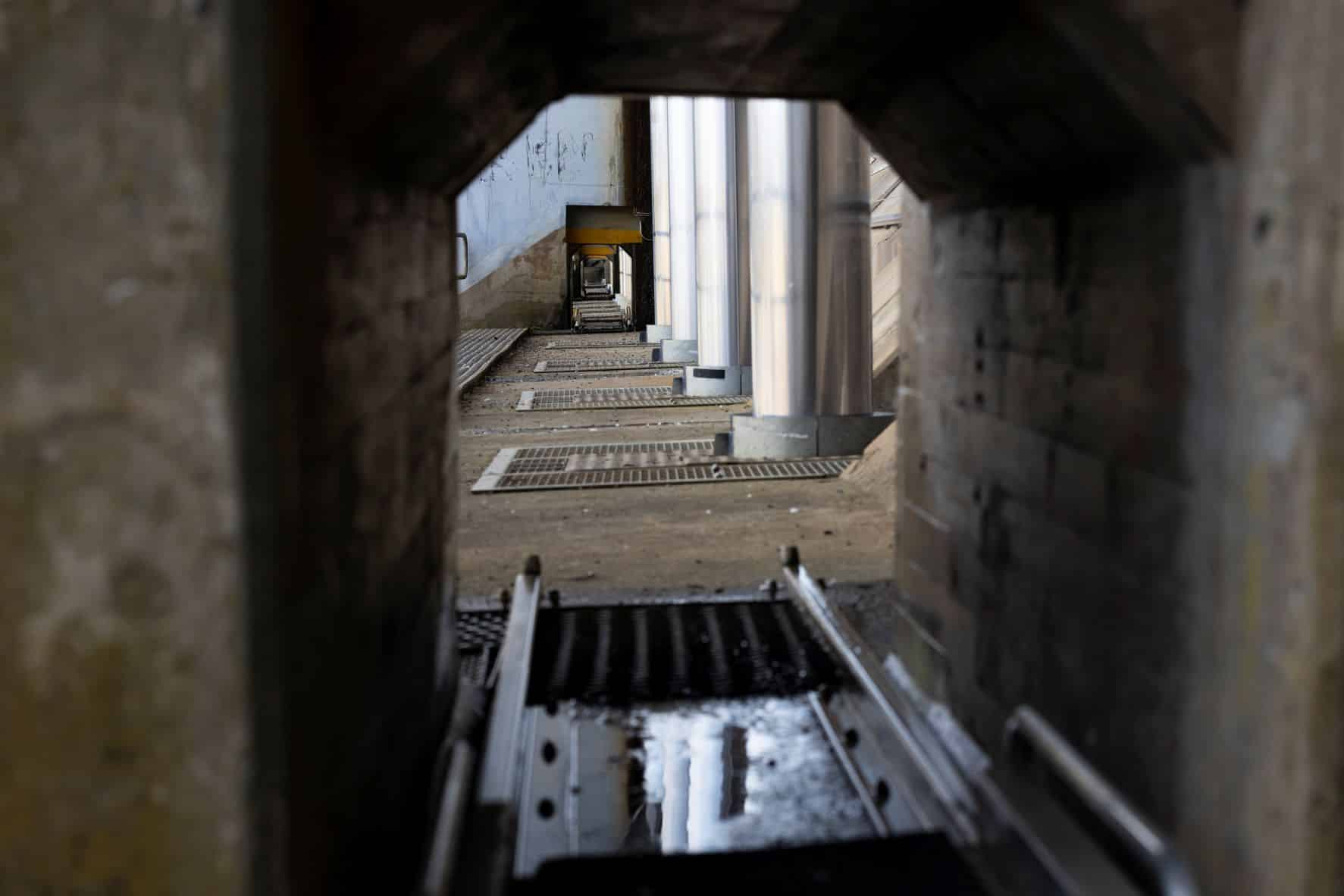

Back outside, we are standing underneath the fish belly gate, which Mr Wright says is quite rare in Australia. On the wall next to the water control system are red lines which mark how much water can be released into the catchment below.

For day-to-day operations, the sluice gates are used. The three low level outlets each have a maximum release of 50,000 litres per second, whereas the five large overflow or fish belly gates each release a minimum of 80,000 litres every second. At full capacity, the flood gates release 8,500,000 litres of water every second – the equivalent of nearly three and a half Olympic swimming pools.

“We really have to pay attention to the water that’s flowing to make operational decisions. Do we lower the level slightly so that we can absorb that difference before operating the flood gate and releasing all that water?” Mr Wright says.

During times of rain, the station is staffed 24 hours a day so real-time operational decisions can be made about how much water needs to be released downstream to maintain the level of the dam. The staff are able to measure the amount of water flowing into rivers and creeks through a number of hydrometric and weather stations spread across the catchment.

Get local, national and world news, plus sport, entertainment, lifestyle, competitions and more delivered straight to your inbox with the Canberra Daily Daily Newsletter. Sign up here.