It’s not marked on your calendar or in Facebook events but it’s currently Bogong Moth migration season and their numbers are on the rise – in more ways than one.

Endangered Bogong moth numbers are higher in number but they’re also higher in altitude because of rising temperatures.

Their final migratory destination in the alpine country – via Canberra – is now about 250 metres higher than usual. Their maximum temperature for aestivating (opposite of hibernating) is 16 degrees Celsius and Mount Gingera in the Brindabellas is already there.

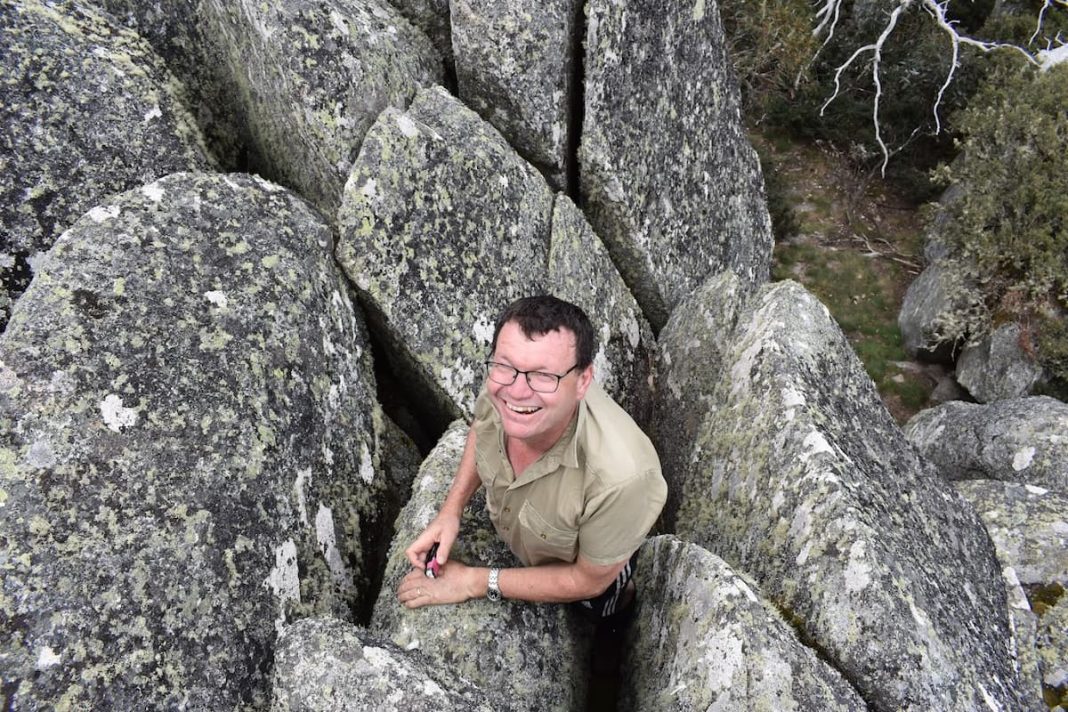

Just ask CSIRO principal research scientist, Peter Caley, who’s climbed Mt Gingera 93 times over the past decade to monitor Bogong Moths.

Peter climbs up to the high country 10 times a year and he’s watched the moths climb too.

“The temperatures are rising, there’s no doubt,” Peter said. “We don’t think they’re running out of real estate just yet but they certainly are moving upslope and they’re getting higher and higher.”

The moths once favoured the rocky crevices on Mt Gingera to above approximately 1600 metres but today they’re found at 1850 metres. Back in 1832, records show they were found at 1500 metres.

“They’re no longer aestivating where they used to,” Peter said. “So whether they run out of space up there, I don’t know, I don’t think so but they definitely go higher.”

As most Canberrans would know, we’re a pit stop along their 1000km migration route. In the ‘80s, tens of thousands of moths swarmed Parliament House like, well, moths to a flame. Their numbers were so great that in 2000, the Bureau of Meteorology once mistakenly thought their swarms were rain clouds, which showed up on the weather radar.

But Bogong numbers have been in decline, hitting rock bottom in the 2017 drought, until recently. While populations are nowhere near as prolific in the rocky alpine country as they once were (17,000 per square metre), they are increasing.

“It’s better than last year for sure,” Peter said. “Compared to 10 years ago, before that very severe drought of 2017 to 2019, I haven’t seen those numbers yet but it’s on the rise, which is a good sign. This year is as good as we’ve seen since the drought, maybe half of what they were before.”

The final count is still underway because moths are still winging their way to the high country. Some fly from southern Queensland, others travel from the Cumberland Plains near Sydney or even as close as the NSW south coast.

Peter is about to set off to the Brindabellas again to survey Mount Gingera, Mount Morgan and also the aptly-named Bogong Peaks in Kosciuszko National Park.

“I’ve got a series of crevices that I shine a torch into and inspect them to estimate what area of moths are in there,” Peter said. “I survey the same sites about 10 times a year to try and find out when they arrive and when they leave. Most of this field work is done in my spare free time.”

If you’re wondering how on Earth Bogong moths traverse such great distances without getting lost, just look up.

Scientific studies carried out in Adaminaby show that Bogong moths use the stars and the Earth’s magnetic field to navigate. Inside a lab, scientists are able to turn off the magnetic field so that the moths don’t know north or south, then scientists project a night sky overhead and watch them navigate by the stars.

While this story is a good-news piece, the Bogong moth is still listed on the Red List of Threatened Species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. More data is needed so if you’d like to be a citizen scientist, log on to Moth Tracker mothtracker.swifft.net.au to report sightings.

If Canberrans want to help the Bogong Moth directly, the moths happen to love Eucalypts, so perhaps plant a few native trees in your yard.

To many locals, Bogong moths are a welcome sign of warmer weather but to Peter, they’re just a “beautiful” little moth with a big drive.

“They’re quite determined,” Peter said. “I do like the fact that when I walk to the mountains they find their way there to these crevices. I think that’s amazing, they’re tenacious.”