From the tragic death of a friend comes a project that would see every person coming to make a home in Australia know how to be safe in and around water – Canberra’s own Refugee and Migrant Swimming Project.

The eleven-week program aims to teach people how to be safe in the water and recognise the danger signs. There are swimming lessons, water information sessions, a crash course in CPR, vocabulary around water safety, all topped off with a freshwater lesson at Pine Island.

In 2020, Najeeb Rafee, a refugee from Afghanistan, was swimming in the Cotter River when an incident resulted in him being submerged for some time. He was transferred to hospital where he died on what would have been his 25th birthday.

“This loss really forced us to think about what was missing in Canberra in terms of water safety and drowning prevention. We came up with the Refugee and Migrant Swim Project to service this gap and prevent other families from dealing with the loss we had,” says co-founder Andrew Nolan.

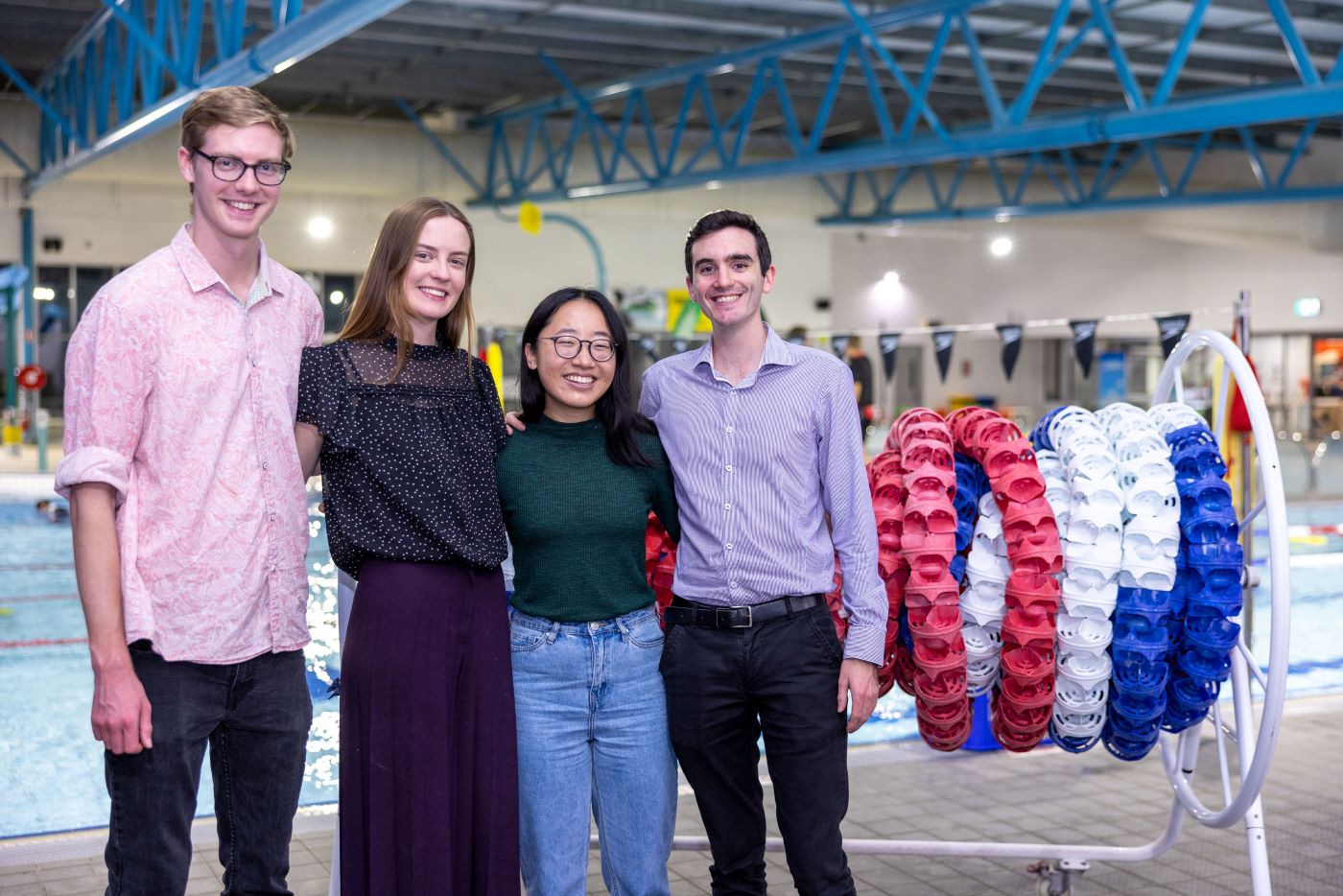

Four of Najeeb’s friends – Mr Nolan, Liam McBride-Kelly, Clare McBride-Kelly and Annie Gao – came together in what they say is a fitting way to continue their friend’s legacy. Najeeb spent much of his time volunteering with other refugee families who had recently arrived in Australia.

Mr Nolan says they reached out to peak refugee and migrant bodies around Canberra and local pools to see if they could get support for their idea. The Gungahlin Leisure Centre came on board and helped launch the first pilot program in January 2022 with 20 participants.

The program is aimed at teaching adults who relocate to Australia how to swim. Mr Nolan says schools have programs for children to learn and Lifesaving Australia has some great programs for younger demographics, but Canberra was lacking a place for adults.

“We want to target adult populations; because they haven’t grown up around water, that increases their risk,” he says.

Mr Nolan says the program targets one of the demographics most at risk of serious incidents in the water; migrants and refugees are disproportionately represented in drowning statistics in Australia, particularly at freshwater sites.

“We see with migrants and refugees that they come to Australia from places that swimming is not necessarily a huge part of their culture and they lack that awareness of what Australian waterways are like and the dangers of them,“ he says.

Being around water and spending time at the beach or in rivers is ingrained in Australian society, says Mr Nolan. Originally from Scotland, he noticed the difference in water culture between the two countries. However, he was lucky that Scotland taught awareness around water safety which people in many countries lack.

“They’re coming from countries like Afghanistan, countries in Africa and Southeast Asia where everything is totally different. Their governments don’t have the funding and that’s not a priority for them,” he says.

The project has found that the best ratio is four or five people per swim instructor and with five instructors on board, they can only help a certain number of people. Their target for a year is 120 participants across two or three different programs. As their classes are free, they rely on grants and the community for help.

So far, from the small grants to the generous Westfield Local Heroes Program, the project has received just over $20,000. This money will allow them to help 130 people successfully undertake the course. Mr Nolan says it also allows them to focus on the longevity of the program to ensure it will be around to help future refugee and migrant families.

Language is a barrier for many of the participants and people coming to Australia, Mr Nolan says, and they also want to undertake every lesson with a trauma-informed approach. This acknowledges that participants come from diverse backgrounds where some may be fleeing war, separation from their family members, and could have water-related trauma.

“One of our participants in our initial pilot program did disclose to us that they had been involved in a drowning incident and that they were scared to get in the water,” he says.

With inclusivity front of mind, Mr Nolan says refugees are the most high-risk group of drowning, and they could be facing cultural and economic restraints that prevent them from mainstream swimming lessons.

“For us, one death – Najeeb’s – was one death too many. We are really trying to prevent this in all the ways that we can,” he says.

It isn’t just the program participants the project supports. Mr Nolan says they are involved in advocacy and were included in Greens MLA Andrew Braddock’s motion for improved water safety infrastructure, which has been accepted by the ACT Legislative Assembly.

“We’re really committed to ensuring that refugees and migrants, but everyone in the ACT, has better access to floatation devices at freshwater sites. There’s increased phone reception and access to emergency phones and improved water safety signage in simple English or accessible in people’s own language,” he says.

Those who have completed the course say it has improved their quality of life by helping them integrate into Australian society and to have confidence around the water. Mr Nolan says the most touching feedback has been from parents who now feel more empowered to be able to watch their kids when going to pools and waterways.

“Not only are we supporting our participants directly, hopefully, this program will have a flow-on effect and people can care for the children and build up swimming ability and water safety knowledge generationally as well,” he smiles.

Find out more about the Refugee and Migrant Swimming Project at rmspcanberra.com

Get all the latest Canberra news, sport, entertainment, lifestyle, competitions and more delivered straight to your inbox with the Canberra Daily Daily Newsletter. Sign up here.