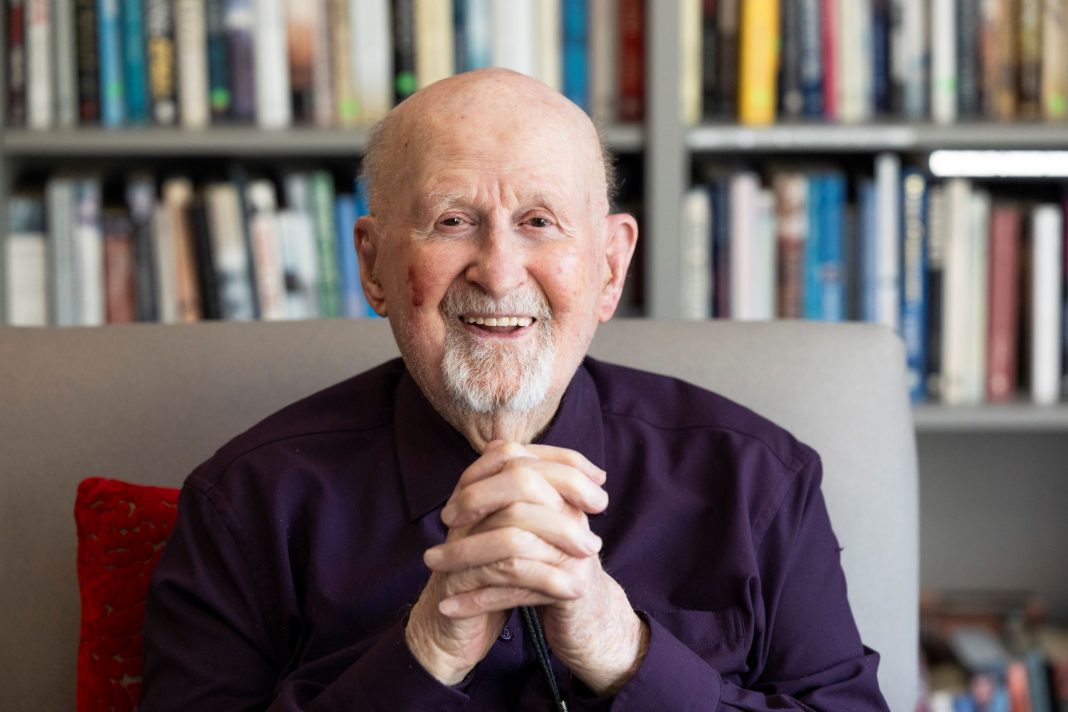

A soldier, minister, public servant, author, family man and upstanding member of the community, Alan Reeve North has spent his 100 years on earth leading a life well lived. He celebrates a century on Saturday 28 October.

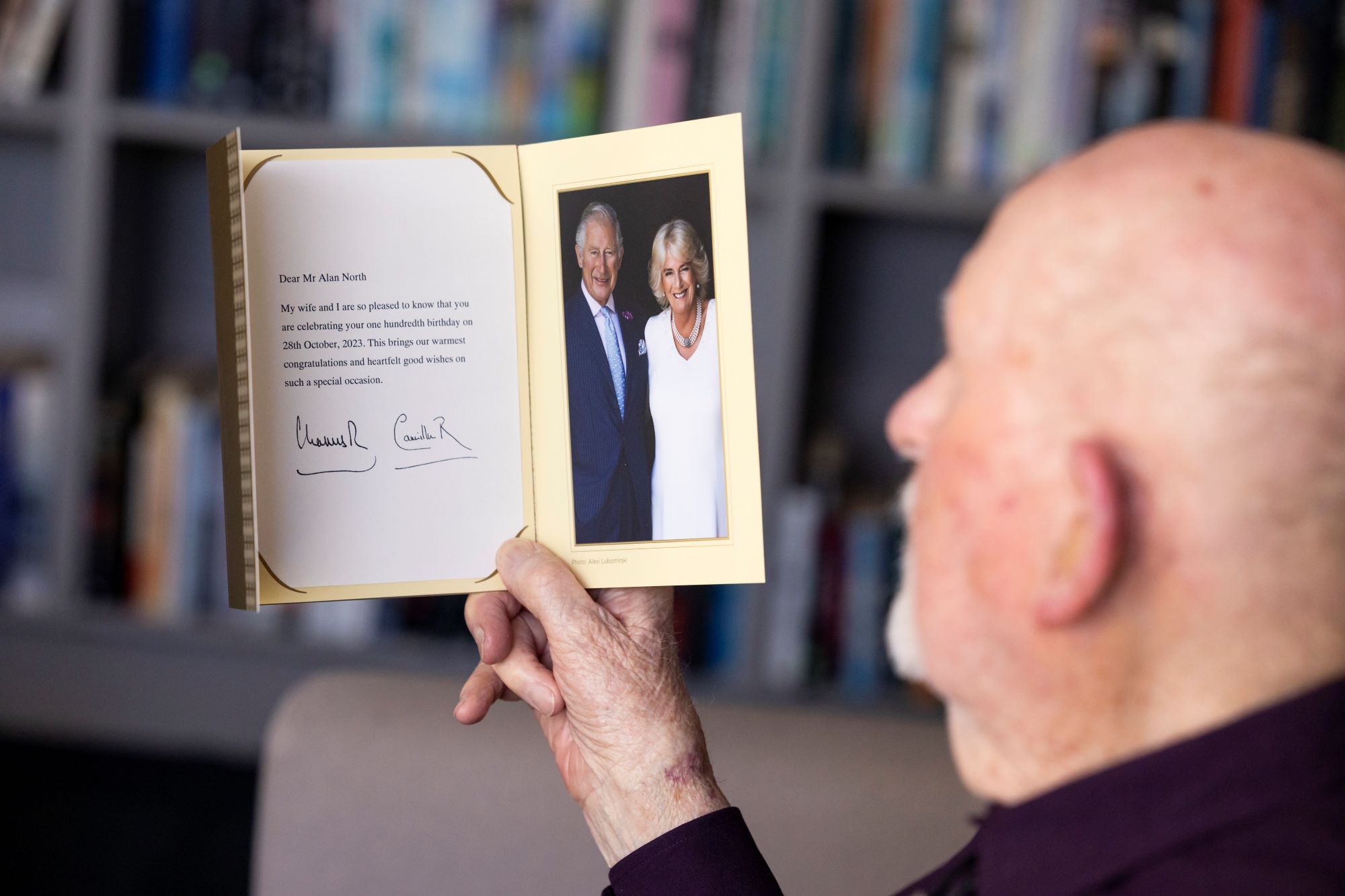

Already receiving letters from the King, Governor-General and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, a momentous birthday deserves to be celebrated – and Alan has two parties planned.

The first happens on the big day at the Yacht Club with family flying from Melbourne, Brisbane and more to celebrate together. Then friends and neighbours from the southside retirement village Alan has called home for the past eight years will celebrate with a morning tea on Tuesday 31 October.

Living independently at the retirement village, Alan’s family says his mind is as sharp as ever and his interest in the world has not waned. This is part of Alan’s secret to long life; a little bit of genes and a never-ending curiosity about the world around us.

“When you stop growing, you’re not learning, you’re not progressing. I think growth is the big word for continuing living,” says Alan.

The second youngest of eight children, Alan was born and grew up in Northgate, Queensland. Alan’s mother was a homemaker, remembered for her amazing cooking, and his father was the local shopkeeper selling groceries, haberdashery and hardware. Alan says he sold everything because he was the only store around.

“We always had our own cow, so we always had milk and cream and butter, always had our chooks, we called them fowls – chickens, ducks. We grew our own vegetables, had our own little orchard, in some ways, we were quite self-sufficient,” he says.

The family had a horse and cart, but the children travelled to school by train each day, hopping on for three stops. After school and on the weekends, Alan filled his days riding bikes with his friends, attending church with the family and playing sport.

“I did play cricket, a lot of cricket. One of my innings I made 147 not out, I was always an opening batsman. When I made over 100, I carried my bat from the beginning to the end, not out. They couldn’t get me out … I was hoping to play for Queensland, but the war came and that was an end to that.”

Early adulthood was disturbed by the Second World War when all 18-year-old men had to enlist in the army, and Alan signed up to serve his country. The troop train took the young soldiers to Cairns before they were sent to Dutch New Guinea, now known as Papua, a province of Indonesia.

“The big population in Merauke were crocodiles; crocodiles were there by the hundreds. If we went on any of the rivers, we had to be very aware, as we were moving up the river there would be crocodiles entering the water every 12 feet apart,” he says.

“Mosquitos were an issue because most of us came down with malaria until a medication was discovered, Atebrin. Atebrin was not a cure for malaria so while we didn’t get malaria in New Guinea, we did after the war.”

Returning home, Alan married the girl he met through a church social at 17. The pair went on to have four children while he also began settling into a career in banking. With the memories of the war still in his mind, Alan wanted to do something that he thought would help other people.

“The only avenue which seemed to be open then was the church, so I did some study and then I became a Presbyterian minister at a few places in Queensland … I only stayed in the church for about five years then went back to banking,” he says.

Family was a vital part of Alan’s life as a child. He and his siblings were close then as they started marrying and having families they moved further apart. However, they spoke often and had family reunions at least once a year.

“When I was young, there was always a piano and we always gathered around the piano to sing every night. There was a lot of family contact, contact with family and much more contact with your cousins and aunts and uncles,” he says.

Moving to Canberra, Alan changed career paths and joined the public service in the nation’s capital.

“It was 1972 and Gough Whitlam had the motto ‘It’s time’, so, strangely enough I had been working in the national bank for 25 years and I thought ‘Oh, it’s time for me to make a change,’” he smiles.

As Whitlam became Prime Minister, Alan took up a role in the Department of Foreign Affairs, then went on to roles in the Australian Development Assistance Bureau and the Public Service Board.

Retirement

Inspired by the famous The Power of Positive Thinking self-help manual by Norman Vincent Peale, Alan is passionate about helping others, often citing words of its powers to others.

“Do all the good you can by all the means you can in all the places you can at all the times you can to as many people as you can as long as ever can … The theme is do all the good you can for as long as ever you can,” he says.

Implementing this philosophy, Alan spent a lot of time volunteering in retirement, and played an instrumental part of the development of the Canberra City Uniting Church on Northbourne Avenue. He also held roles as the president of the Citizens Advice Bureau, vice president of the third Canberra Garden Club, secretary of the Deakin Probus Club, and auditor for National Seniors and Canberra Spinners and Weavers.

In retirement, Alan also started writing books, finishing his first book on family history in 1995. He has written a book on his grandfather, Thomas Mathewson, who is also the grandfather of photography in Queensland. More history has been captured in the two historical war books he later penned.

It was during the research for his first book that Alan had to learn computing. Being a touch typist since high school, he had no problems writing them out and the internet opened a world of research and learning opportunities.

“When I was doing book writing, I needed to discover information back in the 1850s, so I spent a lot of time at the National Library. When I was doing the military history book, I spent a lot of time at the War Memorial and the National Archives. I became well known to the staff at all those places,” smiles Alan.

The internet also allowed him to reconnect and stay in touch with family and friends.

“It certainly was good further education because I could write so much. I wrote lots of letters to family and friends – having access to a computer was certainly of great benefit,” he says.

Now with limited vision, Alan can no longer write any more books. He says as we get toward the end of life it slows down; with impairments like mobility and hearing loss the pace becomes limited.

Alan doesn’t let physical limitations hold him back socially; he uses Siri to make phone calls and every morning he can be seen in the cafeteria catching up with the ladies of the retirement village.

“We get on quite well together. One of the ladies, I hurt my back and she took me in a wheelchair to see the doctor. She pushed me to the taxi then we got a wheelchair taxi back,” he smiles.

Alan says his biggest regret wasn’t travelling enough; for example, he never made it to Europe where he wanted to see the lands of his forebears in England and Scotland. He went overseas with the army and then to Indonesia again when his son was teaching English.

“We thought ‘Oh, if we go to Indonesia, we’ll have to speak the language because Indonesians then didn’t speak English’. We joined a year 11 class for a year, we went to Stirling College to learn Indonesian, so when we arrived in Indonesia, we could understand the language. But the people we met didn’t want to speak Indonesian, they wanted to speak English,” smiles Alan.

Canberra Daily would love to hear from you about a story idea in the Canberra and surrounding region. Click here to submit a news tip.