Mr Albanese’s government has announced a new plan to have the public sector as ‘a participant, a partner, an investor and enabler’ in selecting areas for support, with the focus on ‘clean energy’ and new industries.

There is so much wrong with this.

In particular, the investment in clean energy is already destroying the low-cost electricity and gas that have underpinned our industry and agriculture. And it is doing so with subsidies extracted from consumers and taxpayers that amount to $15.5 billion a year.

Many new businesses collapse but, while the public service can claim a strong record of delivering services honestly and effectively, its record in running or selecting business areas for support is one of unmitigated failure. Think the motor vehicle industry nurtured and cosseted into extinction; Snowy 2’s tenfold cost increase compared with the price announced by Malcolm Turnbull; failed Victorian wind blade factories – to be replicated by government-sponsored green hydrogen facilities and an announced solar panel manufacturing plant.

Though arguably just an extension of the ‘winner picking’ policies long deployed in Australia, the Prime Minister’s plan has met with vehement criticism. An unanticipated one came from the Albanese-appointed head of the Productivity Commission, Danielle Wood. Ms Wood argued that the policy could divert investment from the most productive parts of the economy and risks entrenching subsidy-dependent industries. This was contested by another of the Labor Party’s royalty, former Treasurer and Deputy PM, Wayne Swan, who described Ms Wood as being “completely out of touch with the international reality”.

Resources Minister Madeleine King, attempting to play the honest broker, declared that government will need to be very careful in any cooperation with business but could not just “stand by” while other countries got ahead of the game in critical minerals and rare earths.

Wayne Swan’s strongly held views are disturbing, since he is a major authority within the union-controlled superannuation funds as well as the head of CBUS, with assets that place it among the top 10 funds. He has previously defined “energy transition and housing as areas where super capital can be harnessed”.

While worker participation in Superannuation delivers most people with at least part of their retirement income, the nightmare is that the system will be distorted and use individuals’ nest eggs for political purposes, thereby undermining their value. Superannuation funds control $3.7 trillion of assets (Australia’s GDP is about $2.6 trillion). They can make and break individual businesses, but they can also lose their members’ savings.

Housing – one of Mr Swan’s picks – may well be a useful venue for super funds’ investment. But if the fund managers shift into ‘good hearted’ mode and target the money they control to those they deem worthy, the people whose money they are using could become victims. Super funds should direct their policies at maximising the wealth of their members, leaving the members themselves to determine how much of that wealth should be redistributed to causes and people they wish to support.

In the case of Mr Swan’s other pick, the ‘energy transition’, governments already extend massive support to green energy. That support has largely insulated investors in these ventures from losses. Legendry investor Warren Buffet said, “We get a tax credit if we build a lot of wind farms. That’s the only reason to build them.” But this might not be sustainable – indeed, in the US, a Trump victory in the November elections would certainly bring an unwinding of the subsidies.

Wayne Swan, as the custodian of superannuation finances and also the National President of the Labor Party, has considerable clout to ensure growing Australian government support for the renewable industry sector. He would expect that support to offset the intrinsically higher cost that wind and solar represents compared with coal and gas.

In the past five years, those super funds that adopt ‘Environment Social and Governance’ (ESG) principles (nowadays synonymous with avoiding fossil fuels) have on average performed almost as well as those funds with no such restrictions. Most union-controlled funds exclude or avoid fossil fuel investments. But the risks of investing heavily in ‘green energy’ – and not investing in fossil fuel businesses – are real, even with government subsidies.

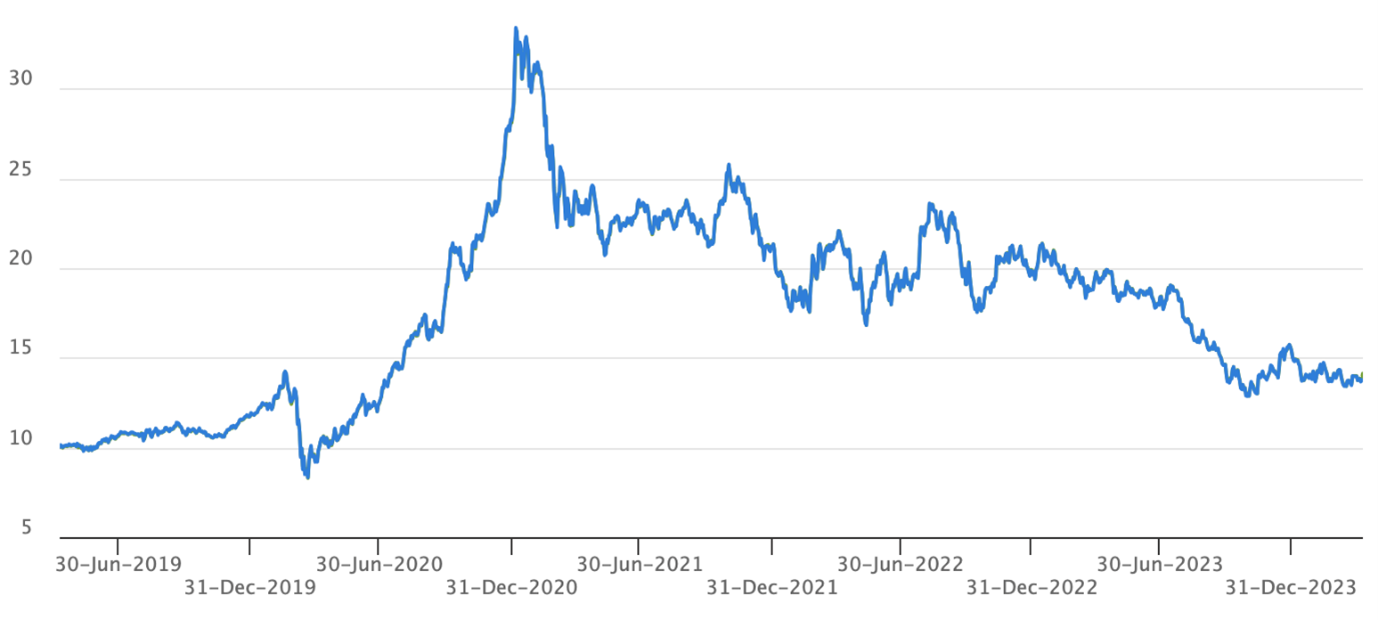

This is illustrated in this chart illustrating ‘clean energy’ investment returns, as measured by the global investment manager VanEck.

While over the past five years the ‘clean energy’ index performed well, over the past three years it has been the worst performing of the 38 indexes monitored by VanEck.

By contrast, an index of eight of the ten global coal stocks recently developed by Range has doubled over the past three years.

While Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet would never allow sentiment to play a role in the investment decisions he makes on behalf of his fund’s clients, we cannot have such confidence in the integrity of political appointees like Mr Swan, who campaign for particular policies.

Editor’s note: Dr Alan Moran was the Director of the Deregulation Unit at the Institute of Public Affairs from 1996 until 2014 and was previously a senior official in Australia’s Productivity Commission and Director of the Commonwealth’s Office of Regulation Review. He played a leading role in the development of energy policy and competition policy review as the Deputy Secretary (Energy) in the Victorian Government.