Millions of Australians use social media to stay informed and express their views, which means false claims can spread rapidly.

The nation’s electoral guardians are concerned that disinformation could undermine trust in how governments are elected, and have updated a toolkit designed to protect trust in the ballot.

Evan Ekin-Smyth, director of digital engagement at the Australian Electoral Commission, told AAP it’s been different in the lead up to May 21 election compared to past polls.

There has always been robust political commentary associated with federal elections, which some people would characterise as attack ads or lies, he said.

But the channels have changed, and it’s becoming more prominent, he added.

Some are picking up claims they’ve seen about the US election being “rigged” and attempting to apply those to Australia.

“We’re certainly seeing more commentary – including ill-informed commentary – regarding electoral processes than we have in previous electoral cycles leading up to a federal election,” Mr Ekin-Smyth said.

Misinformation is defined as the inadvertent, unknowing spreading of mistruths, while disinformation is deliberate.

“We’ve chosen to use the terminology ‘disinformation’ more frequently as it’s the more egregious behaviour,” Mr Ekin-Smyth said.

Research by Twitter shows more than a third of young Australians will get most of their political information from social media during the six-week election campaign.

Politicians and their handlers also need to understand online etiquette.

Some 80 per cent of young people would be turned off voting for a politician who spreads mis- or disinformation online, the survey shows.

Twitter public policy director Kara Hinesley said other leading turn offs include participating in online arguments (53 per cent) and if a politician criticises their opponent on social media (30 per cent).

Whether misinformation or disinformation, officials warn it’s not limited to any one channel or type of channel.

“Of course, we see more on the channels that we are particularly active on – Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube,” Mr Ekin-Smyth said.

“But we also see it on the channels we monitor but are not on, such as Reddit, and from reports we receive about channels that we don’t monitor, such as Telegram.”

Some social media giants, already under scrutiny by governments, are trying to clamp down after online campaigns to destabilise democracy in the US and Europe.

TikTok, which has had a rapid rise in popularity particularly with Australia’s 600,000 first-time voters, last month launched an in-app election guide with the AEC.

The app’s director of public policy Brent Thomas said user guidelines prohibit harmful posts, including content that misleads community members about elections

“We will remove misinformation that causes significant harm to individuals, our community, or the larger public regardless of intent,” he said.

TikTok has also partnered with AAP FactCheck to examine election-related content.

Users can report misleading content by selecting an election misinformation button that will trigger a referral to a team which review alerts and conduct a check.

Every election, the poll is touted as the biggest peacetime operation in history.

Many of Australia’s 17 million voters know the electoral commission for its thousands of voting venues, millions of pencils, and 100,000-plus trusty polling staff.

But there are also AEC data analysts who have a dedicated channel with TikTok, so they can quickly flag content they believe may breach electoral laws or guidelines.

An operations room will be on watch through to polling day for digital and physical threats.

The AEC is active across social media, and has 43,000 followers on Facebook, more than 40,000 on Twitter where it is known for its quirky dialogue with users, but less than 3000 on Instagram.

The commission also releases short videos on YouTube and is publishing a detailed disinformation register online.

The AEC will run a “stop and consider” campaign to remind voters to check the source of all political claims.

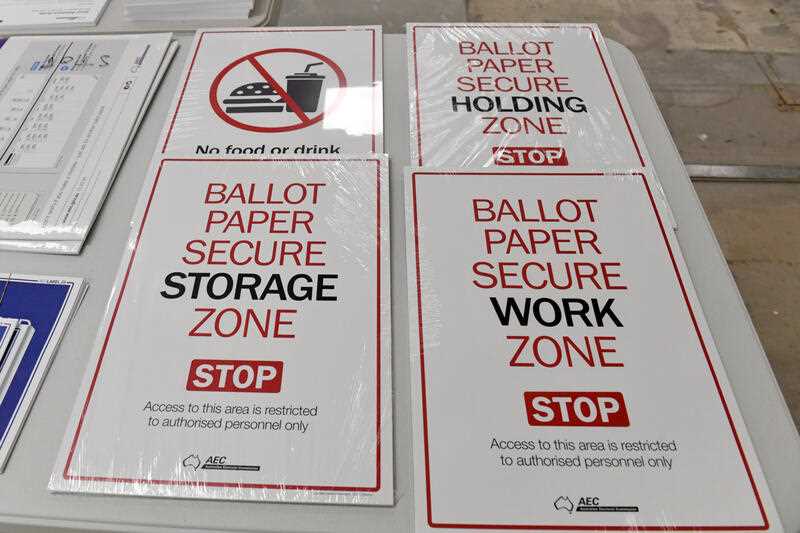

There’ll be further protections while officials complete the count and protect against any infiltration of the process – another aspect that has been ripe for disinformation and needing myth-busting.

As Australian Electoral Commissioner Tom Rogers said, they’re not just providing the logistical operation required for a federal election but also informing citizens about the voting system and how to participate.

Melbourne-based RMIT University’s FactLab will be using digital analysis to detect and track election disinformation.

FactLab uses data analytics and open source intelligence techniques pioneered by London think tank Institute for Strategic Dialogue to tackle the spread of extremism and recruitment online.

The AEC’s Mr Ekin-Smyth warns that “mistruths” are not limited to social media platforms.

“We often find incorrect misinformation in media reports, however this is far more often inadvertent rather than deliberate.”