Australia’s online harms regulator eSafety receives daily reports from private ‘social listening’ firm Meltwater to monitor community sentiment about its Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, newly released documents show.

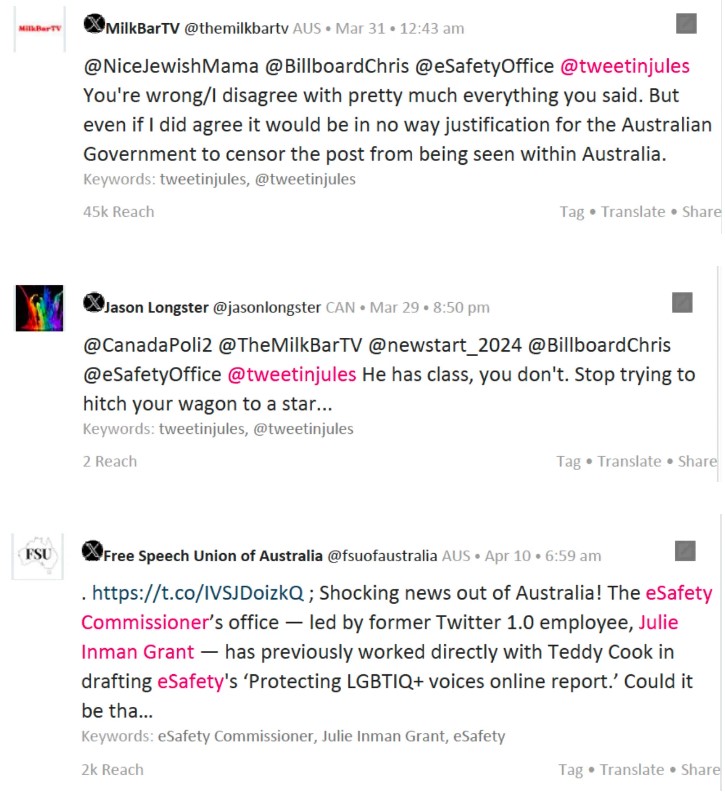

26 Meltwater reports released under Freedom of Information (FOI) show that eSafety receives daily reports, sometimes three or four times per day, documenting social media posts mentioning @eSafetyOffice or @tweetinjules.

The reports, dated from 27 March to 17 April, contain anywhere between 71 to 7,881 mentions, totalling to over 8,000 mentions on several days. These include posts with reach as limited as only two views, and reshares of other users’ posts.

The Meltwater reports are reviewed daily by eSafety’s General Manager, Toby Allan Dagg, according to his testimony in an affidavit filed with the Federal Court on 9 May as part of ongoing proceedings between eSafety and Elon Musk’s social media platform X.

The affidavit includes two reports from Meltwater documenting screenshots of posts on X that mentioned eSafety and/or the Commissioner. The reports were referenced by Dagg to demonstrate “a very large increase” in social media mentions of Inman Grant, particularly on X, since she took legal action against X to force a global ban on footage of a non-fatal stabbing incident, since declared a terror attack.

Last week, a Federal Court judge refused the Commissioner’s request to extend an injunction against X to force a global ban on the footage, ruling that X had taken “reasonable” steps to block the content as required under Australian law, and that eSafety’s request for a global ban was not reasonable.

In the affidavit, Dagg compared Meltwater reporting figures of 239 ‘social mentions’ of eSafety globally on Monday 15 April (the day the incident, called the Wakeley stabbing, occurred), to 31,870 mentions of the Commissioner on Wednesday 24 April, an increase which he attributed to the publicity surrounding the dispute between X and eSafety over the Wakeley stabbing footage.

On 24 April, Inman Grant obtained a temporary injunction from the Federal Court requiring X to immediately hide 65 nominated URLs featuring the footage, under threat of fines of up to $782,500 for every day of non-compliance.

However, this is not the only issue social media users were concerned with on 24 April. Many of the posts featured in the Meltwater report for this day relate to the eSafety Commissioner’s censorship of a post by anti-gender ideology activist and influencer Chris Elston, who posts under the handle @BillboardChris on X.

The incident stirred up public blowback towards eSafety, with even panellists on the milquetoast prime time TV show The Project questioning whether the Commissioner had gone too far. On 17 April, Elston announced that he had initiated appeal proceedings against eSafety, generating further ongoing discussion about eSafety’s activities on X.

Nevertheless, Dagg alleged that with the increase in social media mentions, Inman Grant had been subject to threats and online abuse, causing eSafety to request the assistance of the Australian Federal Police and the New South Wales Police Force to ensure the Commissioner’s safety and wellbeing. Further details of threats to the eSafety Commissioner are included in a separate confidential affidavit.

To prevent threats and online abuse of other eSafety staff, Dagg sought, and was granted, a suppression order to conceal the names and contact details of key eSafety personnel in files related to the legal proceedings. Dagg also secured the suppression of the 65 URLs that eSafety wishes to block so as to prevent people from searching them out.

eSafety was asked for more information about its arrangement with Meltwater. The media department declined to give a formal statement or an estimate of total spending on social insights reporting, but a spokesperson confirmed that Meltwater has been contracted to provide eSafety with social insights reports since 2020.

The spokesperson further explained that the automated reports capture mentions of eSafety and the Commissioner from the public domain across a range of social and blogging sites, from X, to Meta’s Facebook and Instagram, to Reddit. These reports are part of an ‘insights’ package that eSafety uses for broad marketing and PR purposes.

For example, from reviewing social media insights, eSafety can form an impression of community perceptions about its remit and activities, which could inform a future educational campaign. Another example that the spokesperson gave is that if eSafety has been tagged in relation to a potential online abuse incident, a staff person can follow up to provide information about how to report the incident to initiate an investigation (eSafety does not surveil the internet searching out potential harm, but rather responds to reports submitted to its portal).

Social listening’ is ok

Andrew Lowenthal, Founder and Director of digital civil liberties non-profit liber-net , says that eSafety’s arrangement with Meltwater appears to be typical for an agency of its size.

“An agency can legitimately monitor all public mentions of itself, that is entirely reasonable,” he told this author’s news blog, Dystopian Down Under, after the viewing the Meltwater reports. “In fact, a public agency should be monitoring community sentiment, as long as it’s not accessing private information or profiling people – that would not be ok.”

Lowenthal notes that eSafety’s social listening is qualitatively different from other types of social media surveillance carried out by the government, such as the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) contracting M&C Saatchi to surveil social media flagging content for takedown during the Covid pandemic years.

“They were flagging stuff for takedown that was not illegal,” says Lowenthal, who documented the DHA’s censorship activities in an Australian edition of the Twitter Files, which, combined with documents released under FOI request to Senator Alex Antic, revealed that, in an effort to ‘combat misinformation,’ the DHA co-ordinated the censorship of over 4,000 posts of legal (and sometimes factually correct) expression of ordinary Australians.

Targeted surveillance or profiling is not ok

However, social media content creator Nathan Livingstone has reason to believe that eSafety may have engaged in the ‘not ok’ targeted kind of surveillance as well, after his wife received a notification that an eSafety ‘Business Strategist’ had been searching for her LinkedIn page.

In the weeks prior to his wife’s LinkedIn notification, Livingstone had been active on X posting about the eSafety Commissioner’s censorship of Chris Elston’s post.

Livingstone described eSafety’s “intrusive behaviour” in an open letter to the Commissioner posted to X on 20 April, leading him to question – was eSafety investigating him and his family because of critical commentary he had posted to X under his handle @TheMilkBarTV?

“My wife has not interacted with the eSafety Commissioner in any way, in person or online. She has not made any public comments or criticism about Julie Inman Grant or the eSafety Office. Furthermore, her last name is different to mine on LinkedIn and has no affiliation with my content or @TheMilkBarTV,” wrote Livingstone.

“As an Australian citizen, I believe I have the right to know why I am being monitored by my own government, especially when the only possible reason the eSafety Commissioner would be looking into me (and my family) is because of my public criticisms of the office itself.”

In the month since Livingstone sent his letter to eSafety, he has not received a response.

It was Livingstone’s post that prompted this author to submit an FOI request to eSafety for internal communications mentioning Livingstone and his social media account for the time period 18 March to 21 April 2024.

The resultant 26 reports from Meltwater were released to me within days of Dagg’s affidavit publication, confirming that eSafety does actively monitor social media comments about the office, but not revealing evidence of targeted surveillance of particular people or accounts.

“It could have been co-ordinated, or it could just be incompetence, an eSafety staff member snooping on their own time and not using an incognito setting,” said Livingstone of the notification on his wife’s LinkedIn account.

Either way, he said of the social listening reports, in which his X account features heavily, “It’s strange to actually see it – the idea that they’re ‘always listening’, and you see that they literally are.”

“It’s concerning that they appear to be monitoring criticism of their own office,” he said, wondering aloud, “What else is the government monitoring? Criticism of the Prime Minister?”

Yes, actually. Last year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese boasted to assembled press that photoshopped memes featuring himself had been censored as part of a successful effort to combat misinformation.

This is reminiscent of a meme poking fun at a masked Dan Andrews that surfaced in the Twitter Files, revealing that the DHA, which is responsible for important issues such as immigration, border security and counter-terrorism, had seen fit to censor a great Australian pastime – making jokes about people in authority.

Government censors always go too far

Amusing as these instances may be, they signify a core problem in the government’s approach to censorship across its various departments and agencies, which is that given an inch, they tend to take it too far.

Returning to eSafety, Lowenthal said that while social listening is not a problem per se (notwithstanding Livingstone’s personal experience), eSafety has engaged in some “inappropriate censorship.”

While Lowenthal recently told independent journalist Maryanne Demasi that he is not in favour of a free-for-all on violent content on social media, he called the eSafety Commissioner’s global takedown order “ridiculous.”

“In both the Twitter Files and in this case [of eSafety trying to globally block the Wakeley stabbing footage], the Australian Government has tried to declare itself sovereign over the entire internet,” he said.

“Censorship and surveillance crosses the line when it tries to police content that is outside of Australia’s jurisdiction, and when it tries to police opinions and hurt feelings,” said Lowenthal.

On the former point, Justice Geoffrey Kennett, the Federal Court judge who refused eSafety’s application to extend an injunction against X, concurs.

“Apart from questions concerning freedom of expression in Australia, there is widespread alarm at the prospect of a decision by an official of a national government restricting access to controversial material on the internet by people all over the world,” wrote Justice Kennett in his decision.

“The potential consequences for orderly and amicable relations between nations, if a notice with the breadth contended for were enforced, are obvious. Most likely, the notice would be ignored or disparaged in other countries.”

On the latter point, the eSafety Commissioner’s moves to censor opinions on gender ideology appear to have backfired in full Streisand-effect fashion, drawing intense focus on the regulator and its activities, as well as fuelling public debate on the topics of gender medicine and sex-based rights.

“I don’t think Julie Inman Grant has any real influence except to ensure the speech she doesn’t like is magnified by her authoritarianism,” remarked Elston wryly in an email to Dystopian Down Under. As mentioned above, Elston has initiated appeal proceedings against eSafety over the censorship of his social media post on X, and has repeatedly thanked Inman Grant for the attention she has brought to his activism in the process.

Where there is overreach, there will be blowback

In some corners, eSafety’s overreach has provoked a backlash to the point that there are calls for the online harms regulator to be abolished altogether. The Free Speech Union of Australia’s (FSU) petition to ‘end eSafety’ has garnered over 13,000 signatures.

FSU Australia has also created an online tool for social media users to “find out if they’re being spied on,” with an option to request that eSafety provide a public response via X. This will undoubtedly create even more mentions of eSafety and Inman Grant on X as responses are shared across the platform.

For Livingstone, eSafety’s inappropriate censorship and the prospect of a more targeted investigation of his family’s social media accounts have made him “want to go harder” in expressing criticisms of eSafety’s conduct. “My formal complaint has over 250,000 impressions,” he says. “I’ve tried to bring some awareness.” And that he has.

eSafety was asked to comment on the court proceedings with X but can only confirm that the matter is still in progress. A final hearing is expected to take place in the coming months.

To support Rebekah’s work, share, subscribe, and/or make a one-off contribution to DDU via my Kofi account.

FOI Meltwater social listening reports 27 March to 17 April 2024: PDF file Download