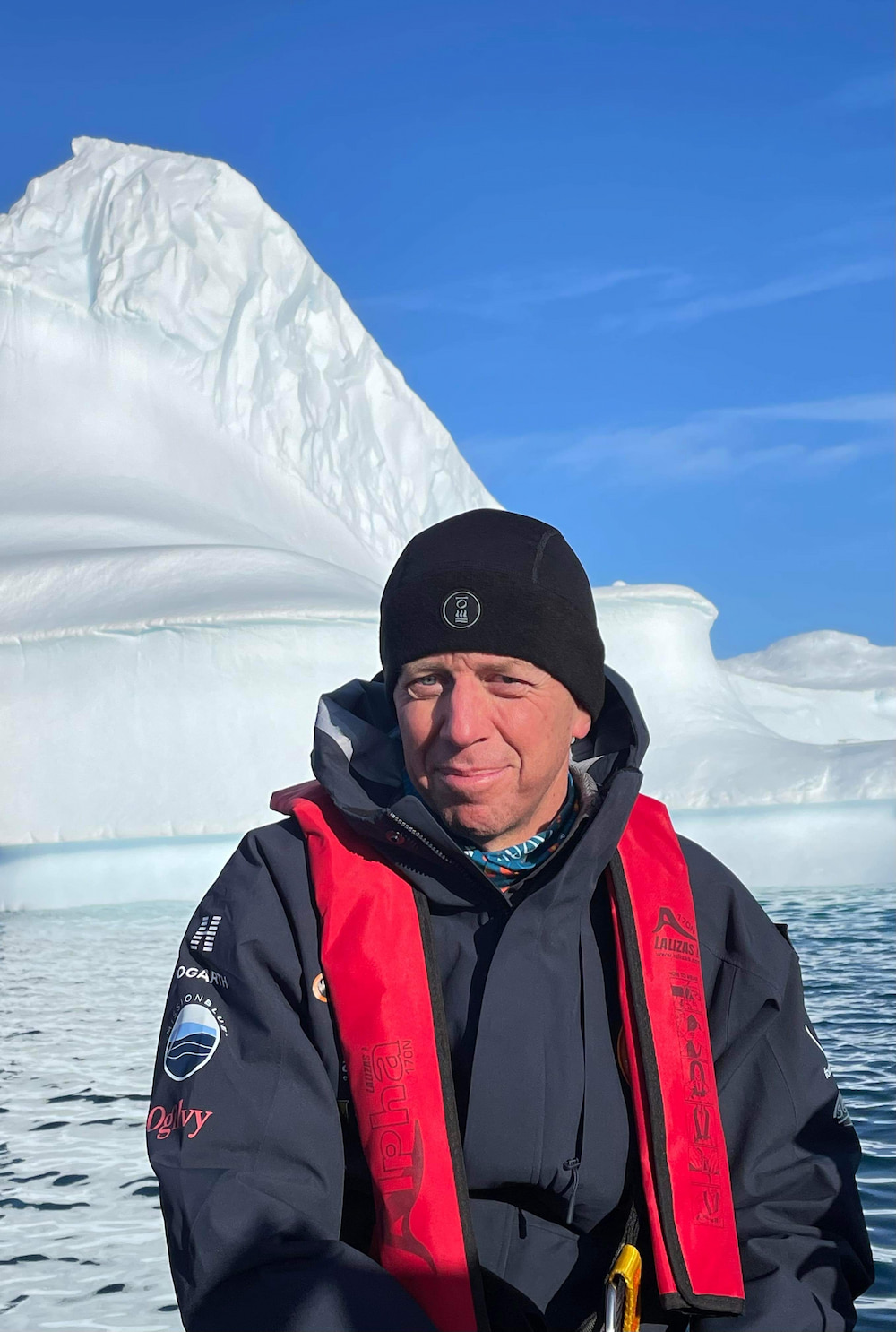

Nearly 20 years ago, Shane Rattenbury went to Antarctica to lead Greenpeace ships tracking the Japanese whaling fleet. Last month, the ACT Greens leader returned to the great white south, under very different circumstances: “An expedition about science, education, and public participation.”

He was one of 110 ambassadors to the Antarctic Climate Expedition, a floating climate summit and nine-day voyage aboard the Sylvia Earle, a carbon-neutral vessel named after the American marine biologist, oceanographer, and Time Hero of the Planet, who also led the expedition.

“It’s an extraordinary part of the world, and it’s a privilege to go there and to see the beauty of Antarctica,” Mr Rattenbury said. “But clearly there was a serious element to the Expedition, which explored issues of climate change … Antarctica is really at the forefront of climate impacts.”

While the Expedition was underway, the BBC reported that, for the second year running, sea-ice was at its lowest since records began in 1979. CSIRO predicted that stronger El Niño events due to climate change could accelerate irreversible melting of Antarctic ice shelves and ice sheets.

Scientists predict melting ice will cause sea levels to rise, with grim consequences. Earlier last month, UN Secretary António Guterres warned that low-lying communities and even entire countries could disappear; billions of people could be displaced; and there could be fierce competition for fresh water, land, and other resources.

Reduced sea-ice, Mr Rattenbury said, would also affect the production of krill, a small, shrimp-like creature that is at the base of the food chain in Antarctica. “Penguins, seals, whales all feed on krill – and so, if krill production declines, this could have a catastrophic impact on the species that depend on krill as well.”

But it’s not too late.

“There is still time to turn things around,” Mr Rattenbury said. “There will be some impacts on Antarctica, but the question we are faced with is: are we prepared to take the action now that will minimise those impacts? Or are we going to simply turn a blind eye, and allow those great impacts to occur in Antarctica which will impact all of us?

“It is a clarion call that this is the critical decade. Now is the time we have to cut emissions. We can’t allow new fossil fuel projects; we should not open coal mines [or] gas fields. If we want to save Antarctica, now is the moment to act.”

The Expedition’s purpose is ‘to raise awareness of the importance and splendour of the Antarctic, and address warming climate and loss of ice in the southern polar region as a direct threat to the future of human life on this planet’.

To that end, the Expedition participants formulated 23 resolutions to get to net zero by 2050. They include empowering young people to become the next generation of leaders; reducing fossil fuel use in marine applications (shipping), and reducing plastic use.

“Antarctica’s about as far from civilisation as you can get,” Mr Rattenbury said – and yet the Expedition’s survey showed microplastics in the ocean. “Plastic production requires a significant amount of fossil fuels,” Mr Rattenbury noted.

But the ACT’s work on climate change can make a difference internationally, Mr Rattenbury argues, as his lecture about how midsized cities can change the world showed. The ACT, Mr Rattenbury’s profile for the Expedition states, is “a global leader in climate action”, powered by 100 per cent renewable electricity. The Expedition organisers invited him on behalf of the Territory because, he said, they were “very inspired” by how the ACT reduced emissions to 46 per cent below 1990 levels.

- ACT a ‘nation-leader’ in renewable energy (4 December 2020)

- Canberra will become the renewables energy capital of Australia (18 December 2021)

His other reasons for being aboard were to inspire others to take greater action, to create more networks for the ACT, to find out what other jurisdictions were doing, and to share policies about reducing emissions.

“The ACT’s made real progress in some areas … but gas and transport in particular, we’ve still got work to do,” Mr Rattenbury said.

He found it particularly useful to discuss the communications and education side of the climate debate (how to talk to communities about climate action), and scope three greenhouse gas emissions (indirect emissions from goods and services) – an area the ACT has only just begun to explore, Mr Rattenbury said. In 2021, with the Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment’s report, the ACT became the first jurisdiction in Australia to calculate these emissions, and consider how to reduce them.

- ‘Globally ambitious’: ACT first to calculate indirect greenhouse emissions (11 November 2021)

“There’s a lot of follow-up work to be done from the trip,” he said: a feature documentary, exhibitions, and a book.

But it wasn’t all hard work and high-level policy discussions. Mr Rattenbury relished seeing whales in the wild.

“One of the really beautiful parts of the trip for me was one afternoon when we were at anchor … we had a minke whale come up to our ship and swim around, poking its head above water to look at us in a very leisurely way.

“The last time I saw a minke whale was seeing one harpooned, with a grenade-tipped harpoon.”

That was in 2005, when Mr Rattenbury, then the head of Greenpeace’s global oceans campaign, led a protest to Antarctic waters against Japanese commercial whaling (or ‘scientific research’).

“At that time, we were literally on the high seas, interfering with the Japanese whaling hunt,” he recalled. “It was dangerous … Seeing whales being harpooned is a very visceral experience …

“It was a really beautiful experience for me to see minke whales the way we should see them: magnificent creatures in the ocean, who are an important part of the ecosystem, and should be free to swim the waters of Antarctica not being chased by a whaling vessel.”

He was struck by the abundance of species in Antarctica: whales, seals, penguins, and birds.

“All of those creatures are highly visible in the summer months, particularly before they migrate north again,” Mr Rattenbury said. “Seeing all those wild animals was a wonderful experience. And, of course, the beauty of Antarctica: icebergs, ice-capped mountains, glaciers.”

But the juxtaposition of that beauty with the scientific reality – the rate of retreat of the ice cover and Antarctica’s threatened future – was poignant, Mr Rattenbury found.

“Having that opportunity to go to Antarctica, witness it firsthand, and to be briefed on the political consequences if we don’t act now was very powerful,” he said.

“It’s something I hope to share with others, and inspire both political leaders and regular members of the public that we all need to do our part in tackling climate change as quickly as we can.”