Mystery in style – Tempo Theatre returns to Agatha Christie for the first time in three years, with Murder on the Nile.

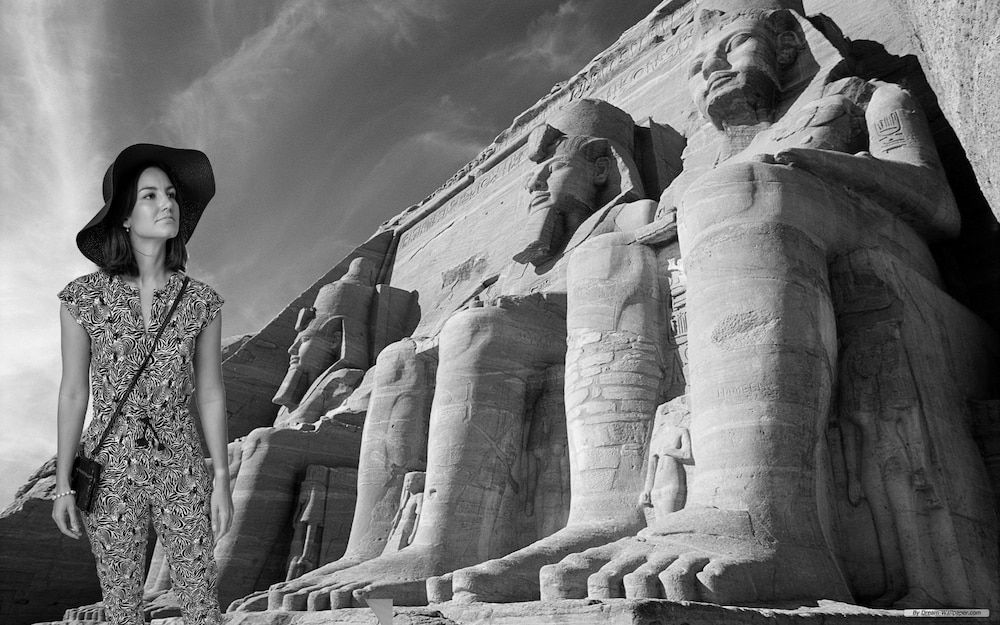

In the sultry stillness of the Egyptian night, aboard the Nile paddle boat Lotus, a shot rings out – a scream pierces the air – and a young woman is found dead in her cabin – murdered…

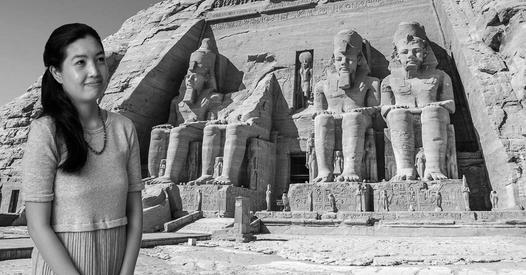

Who killed glamorous Kay Mostyn (Jacqueline Forrester)? She was the girl who had everything: wealth, beauty, and her best friend’s fiancé, Simon (Mark Ritchie).

Poor jilted Jackie (Kim Wilson) stalked the couple on their honeymoon, threatening to put her dear little pistol against Kay’s head and gently press the trigger. Too obvious?

Was it Kay’s guardian, Canon Pennefather (another Kim Wilson)? Had he helped himself to her money to build his new Jerusalem? Was it the foreign doctor (Paul Jackson), whose father was ruined by Kay’s? The hot-headed young Socialist (Sam Kentish), tired of waiting for the workers’ revolution? The domineering dowager (Marian FitzGerald), or her put-upon niece (Sarah Jackson)? Or the envious French maid (Kah-Mun Wong)?

“All these people arrive on the boat: half of them have a connection to Kay Mostyn, and half of them have a grudge against her,” director Jon Elphick says. “Murder and mystery ensue.”

And the killer is ready to strike again…

Murder on the Nile, opening at Belconnen Theatre this month, is Elphick’s eleventh Agatha Christie for Tempo Theatre.

“There’s a mystery to solve, there’s a puzzle to solve – and it’s just good fun, really,” Elphick says. “It’s not serious, it’s not dangerous; it’s just good entertainment… People like to solve mysteries and puzzles. It’s part of everyone’s DNA.”

Christie’s detective stories – 66 novels and 15 short-story collections – are, as he points out, outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare.

“I like Christie – everyone likes Christie,” he explains. “She writes very simply, and her writing is readily available to a wide audience, which is why she’s the most popular author on the planet, even still.”

The play is Christie’s own adaptation of her 1937 novel, Death on the Nile, one of her finest works, featuring her urbane Belgian sleuth, Hercule Poirot. While many associate Christie with country houses and villages, several of the 1930s Poirot novels are set in the Middle East, a region Christie knew well; she spent half of each year working on archaeological sites in Iraq and Syria with her husband, Max Mallowan.

Nile was praised at the time for its exotic setting (“it hits the Nile on the head”), its admirable characterisation, and its surprise solution (“Mrs Christie’s dénouement, as usual, plays us all for suckers”). John Dickson Carr, one of Christie’s few peers in the genre, declared: “You will find Poirot at the top of his form in Death on the Nile, which I venture to think the best of what [the Observer critic] Torquemada called ‘the little grey sells’. If you spot the murderer, you deserve a medal.”

Its combination of romance, travel, and murder has been irresistible to filmmakers. The lavish, star-studded 1978 adaptation, with Peter Ustinov as Poirot, is by far the best screen version; the 2004 David Suchet TV movie is sour, while this year’s blockbuster vehicle for Kenneth Branagh strays too far from Christie’s story and tone.

But when Christie herself adapted her novel for the stage, she removed Poirot altogether.

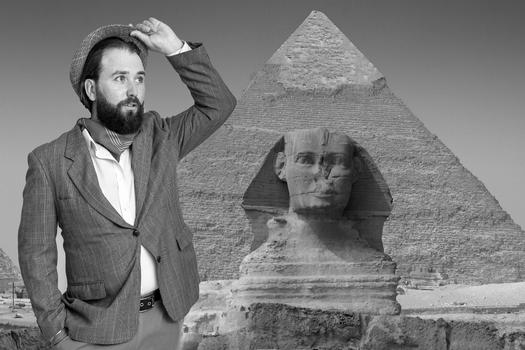

The play was written for Francis L. Sullivan, who played Poirot twice: in her first play, Black Coffee (1930), and then in a 1940 adaptation of Peril at End House, by Arnold Ridley (later famous as Private Godfrey in Dad’s Army). But Christie felt Poirot would distract the audience.

“Hercule Poirot was utterly unsuited to appear in any detective play,” she told Sullivan, “because a detective must be necessarily the onlooker and observer, and can only succeed if he abandons detection for positive action. That is, he should not be in a detective play but in a thriller.”

Instead, Sullivan played the avuncular Canon, a combination of a few characters in the play, Elphick explains.

“But the basic story’s the same. Some of the characters have been changed, but the basic story’s definitely the same.”

Nile was first performed at the Dundee Repertory Theatre in 1944. In its original version, it seems to have been a J. B. Priestleyesque ‘time play’: the last two acts turn out to be a vision of what might happen.

The play that reached London a couple of years later, after a pre-West End tour of the provinces, was less radical. Initial reviews were enthusiastic.

“Plenty of excitement and thrills,” The Stage wrote, reviewing a 1945 Wimbledon staging. “It is a cleverly worked-out play.”

But it only had a short run in the West End, where management had cold feet after the failure of a previous Christie play; and an even shorter run in New York, where bloodthirsty American audiences preferred Christie’s multi-murder hit, Ten Little Indians.

But it has played well in community theatres worldwide for decades.

It is also entertainment with a heart. By 1937, Christie reigned supreme as Queen of Crime, world-famous for brilliant puzzle plots – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) or Murder on the Orient Express (1934), for instance – but she was increasingly interested in ‘why’ as much as ‘whodunnit’.

She was fascinated, she wrote in an article for (of all things!) Soviet Russia, by “the preliminaries of crime. The interplay of character upon character, the deep smouldering resentments and dissatisfaction that do not always come to the surface but which may suddenly explode into violence.”

Her 1940s works have less elaborate plots, but deeper characterisation; Five Little Pigs (1942) is a murder in retrospect, narrated by the suspects 20 years later, for instance, while The Hollow (1946) is more a straight novel about love and betrayal than a mystery.

Nile, her longest novel, is both one of her most brilliant problems, and features some of her richest characterisation: a romantic triangle surrounded by a dozen vivid, shrewdly observed others. Christie delays the murder to nearly halfway, giving the reader time to know the passengers as people, rather than just suspects. The play develops these elements further; it is almost a drawing-room (or steamer saloon) drama with detection.

“We’ve got a great cast,” Elphick says. “Half the cast are experienced Tempo people, and half the cast are people who haven’t done that many shows. It’s a good mix.”

Tempo’s Agatha Christie plays, he says, have always been popular, from Towards Zero (2019), the most recent one, and The Mousetrap (2011), the longest-running play in history, to And Then There Were None (2004) and A Murder is Announced (2002).

“People know what they get with a Tempo show. They get a good quality show with great acting, and they get an entertaining show. We don’t try and oversell it. We don’t change it. For those Christie fans, we don’t send it up, we don’t turn it into a comedy. We just do this as it’s written, and people seem to react to that, and enjoy the shows.”

Will you pit your wits against the cunning of Agatha Christie, the serpent of old Nile?

Tempo Theatre presents Murder on the Nile at the Belconnen Theatre, 21-29 October. Tickets are available from Canberra Ticketing or phone (02) 6275 2700.

- Nicholas Fuller plays the Steward.