US politics will start with a bang in January 2024. The long-awaited Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primaries promise to provide early clarity on a likely Donald Trump v Joe Biden rematch for the presidential election this year. But beneath the hoopla of the first-tier White House candidacies will be another race – the sprint to get on the ballot for those not running as Republicans or Democrats.

Independents Robert F. Kennedy Jr and Cornel West are already filing their paperwork and hitting the campaign trail, while others – including Democrat senator Joe Manchin and entrepreneur Andrew Yang – are reportedly weighing their options.

Third-party candidates in the US always prove controversial. Not just because the two-party system is so ingrained into the country’s consciousness. But because, almost by definition, anyone who runs without an “R” or “D” on the ballot has the potential to play spoiler.

Duverger’s law, named after the 20th-century French social scientist Maurice Duverger, makes a simple prediction: election systems such as in the US, with single-member districts and winner-take-all voting, invariably trend toward two parties.

That means if 2024 is a rematch between Biden and Trump, there’s almost zero chance of a third-party candidate snatching victory. Yet none of this changes a simple fact: a third-party candidate doesn’t have to win to play a starring role in who’s given the keys to the Oval Office.

Tipping the balance

Could a third-party candidate really tip the balance in 2024? In short, absolutely. In 2016, some 80,000 votes breaking differently across three states — Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — would have ensured a Hillary Clinton victory. Today, polls in a hypothetical Biden v Trump match look like a statistical dead heat, giving even more of an opening for a third-party candidate to be a gamechanger.

A survey in early 2024 by left-wing thinktank Data For Progress, for example, found that a “moderate, independent candidate” would draw 13% of the vote and grant Trump a slight edge in the popular vote over Biden.

To the extent that this tracks outcomes in swing states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Florida and elsewhere, even a candidate who could earn a much lower percentage could tip the balance in a razor-tight election.

History also suggests that third-party candidates can be decisive. In 1992, for example, business tycoon Ross Perot earned nearly 19% of the national popular vote. Although he failed to carry any state in the electoral college, he helped ensure Bill Clinton’s victory over George H.W. Bush.

In 2000, liberal activist Ralph Nader, who ran on the Green Party ticket, paved the way for George W. Bush’s narrow defeat of Al Gore, particularly in the decider state of Florida.

In 2016, experts crunched the numbers and found that, if all the votes captured by Green Party candidate Jill Stein had gone to Clinton, she would have won the requisite 270 electoral votes to be president.

Contenders (and potential contenders)

Given the overwhelming majority of Americans who aren’t excited about a 2020 election rerun, it’s unsurprising that the last year has been filled with “will they, won’t they?” speculation about what third-party candidates might jump into the race.

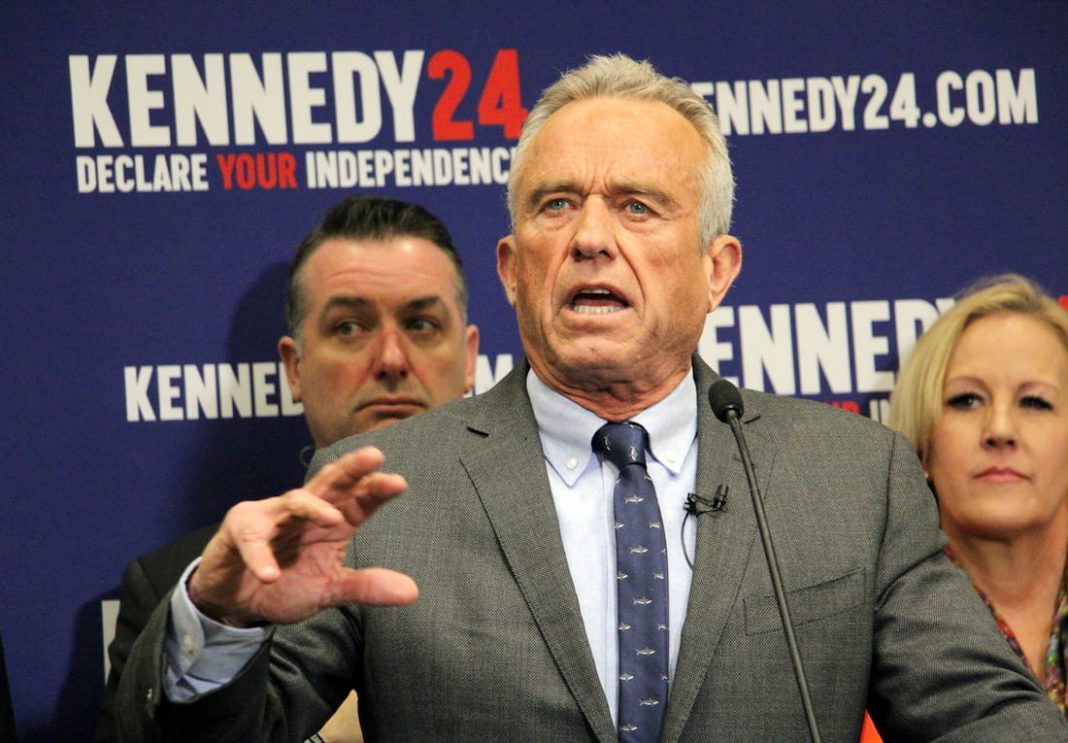

Robert F. Kennedy Jr, the nephew of former president John F. Kennedy Jr, declared in October he was running for the White House as an independent, after suspending his flagging bid to challenge Biden as a Democrat.

A former environmental lawyer with a populist message that appeals to both progressives (he supports minimum wage hikes) and some hardline conservatives (he’s sceptical of vaccines), RFK Jr is the candidate most likely to shake up 2024. Almost one in five Americans would consider voting for Kennedy, according to a recent Monmouth University poll.

No Labels, which bills itself as a “national movement of commonsense Americans”, is the organisation with the money and legitimacy best poised to put forward a different major third-party candidate. Although no one has yet committed to running under its banner, rumours have swirled around at least two names.

Andrew Yang, the only politician to confirm “conversations” with No Labels, founded the centrist Forward party in 2021. A former business executive who also ran unsuccessfully for president in 2020 as a Democrat and for mayor of New York in 2021 as an independent, his campaigns have produced a loyal, modest base, the “Yang Gang”.

Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat senator from West Virginia, could also grab the No Labels mantle. Manchin has been a thorn in Biden’s side during his three years in office, slowing and altering the passage of several major pieces of legislation, such as the signature Build Back Better Act. Yet the question is whether he’d risk his long political legacy only to help Trump return to power.

Outside of No Labels, other candidates may also find their way onto the ballot in a small number of states. Cornel West, the black theologian, academic and activist, is perhaps the most notable. Previously part of the Green Party, West recently announced that he would run as an independent to, in his words, “end the iron grip of the ruling class”.

‘Rematch from hell’

An irony is that virtually no Americans seem satisfied with their likely choices for president. A New York Times headline has called 2024: The Biden-Trump rematch that nobody wants. One Congressman has decried it as “the rematch from hell”.

For that reason alone, a third-party contender who catches fire, or gains even a modicum of momentum with the politically “homeless”, could provoke a wild and unpredictable election night.

Highly partisan nomination systems, dominated by tiny fractions of voters in unrepresentative states, seem to guarantee Americans the presidential nominees they don’t want. Yet while there’s plenty of appetite for busting up the two-party monopoly, Duverger’s law is a law for a reason. Third-party candidates can play spoiler. But what they can’t do is win.

Thomas Gift, Associate Professor and Director of the Centre on US Politics, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.