Some infectious diseases strike fear into our hearts at the very mention of their name. Smallpox is one such disease and many older Canberrans still bear the pock-shaped scar of a smallpox vaccination they received prior to 1980 when the vaccination was discontinued.

But what if smallpox wasn’t the formidable killer it’s reputed to be? What if it was a mostly mild disease?

As a research analyst, I have delved deeply into the answer to these questions in Dissolving Illusions – a book I co-authored with US nephrologist Suzanne Humphries.

Although on the surface it sounds like a completely ridiculous idea, throughout history some doctors have documented that smallpox was a mild ailment when appropriately managed and not mishandled.

The following excerpts from the book provide food for thought about the evolution of smallpox.

1600s

In the late 1600s, the gold standard treatment of smallpox involved keeping the patient in a hot environment and possibly covering them with blankets to induce sweating. Patients were given cordials made from various herbs, spices and alcohol to increase internal heat or circulation. It was believed that this could help expel harmful substances and promote healing.

MD Thomas Sydenham, renowned as the English Hippocrates and regarded as the father of English medicine found these treatments turned smallpox from a mild disease to one that could be deadly – a sentiment agreed to by MD John Pechey in 1696:

“…the Small-Pox being too much forced out, by giving Cordials, and by a hot Regimen run into one, a foul Spectacle, and one that threatens a sad event; and these and the like Symptoms are usually occasioned by these Errors; whereas I never observed any mischief from the other Method: For Nature, left to herself, does her Work in her own time, and separates, and the expels the Matter in the right way and manner...”

John Pechey, MD, The Whole Works of that Excellent Practical Physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham, MD, 1696, London, p. 100.

1700s

In the early 1700s, Isaac Massey, an apothecary at Christ’s Hospital, observed that smallpox was rarely fatal when managed with appropriate treatment.

“…a natural simple smallpox seldom kills, unless under very ill management, or when some lurking evil that was quiet before is roused in the fluids and confederated with the pocky ferment.”

Isaac Massey, Remarks on Dr. Jurin’s Last Yearly Account of the Success of Inoculation, 1727, London, p. 5.

Having attended to patients at Christ’s Hospital which housed around 600 children a year, Isaac Massey observed that over a 20-year period only 5 or 6 deaths were attributed to smallpox. He believed that the ‘newfangled’ notion of inoculating people with pus from a smallpox lesion was unnecessarily dangerous.

1800s

In 1814, John Birch a distinguished member of the Royal College of Surgeons expressed his belief that a significant number of smallpox fatalities were attributable to poor diet, unclean environment and medical error.

As years went by, smallpox treatments became increasingly severe and included bleeding patients to the point of fainting, withholding water, depriving patients of light and fresh air, and administration of Calomel – a mercury-based compound which was used to treat a wide range of illnesses to induce vomiting and diarrhoea.

In 1889, Dr Henry G Hanchett stated why he believed so many diseases including smallpox were fatal:

“We can recognise the mistakes of our predecessors and those of some of our contemporaries. We wonder that the old-time doctor did not suspect that his lancet, his calomel and tartar emetic, put many a patient underground, whose disease would have ended in recovery if it had been let alone.”

Henry G. Hanchett, M.D., “An Inquiry in Prophylaxis,” The New York Medical Times, vol. XVI, no. 10, January 1889, p. 306.

At the end of the 1800s smallpox became a mild disease. After the summer of 1897, the severe type of smallpox with its high death rate, with rare exceptions, had all but disappeared from the United States.

“During 1896 a very mild type of smallpox began to prevail in the South and later gradually spread over the country. The mortality was very low and it was usually at first mistaken for chicken pox.”

Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913, p. 173.

1900s

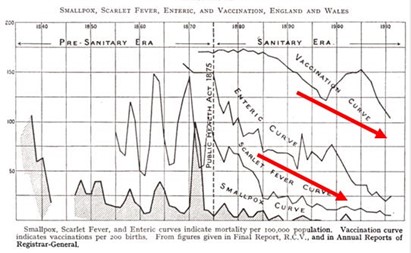

By the early 1900s, there were those who recognised that the introduction of sanitation had done what vaccination had failed to do – conquer smallpox. Smallpox vaccination was on the decline and yet smallpox, like other diseases, was disappearing as a major threat.

In 1914, Dr. C. Killick Millard wrote the book The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration. In it, he draws the parallel between improved sanitation and improved health outcomes in the England.

“For forty years, corresponding roughly with the advent of the ‘sanitary era’, smallpox has gradually but steadily been leaving this country (England). For the past ten years the disease has ceased to have any appreciable effect upon our mortality statistics. For most of that period it has been entirely absent except for a few isolated outbreaks here and there. It is reasonable to believe that with the perfecting and more general adoption of modern methods of control and with improved sanitation (using the term in the widest sense) smallpox will be completely banished from this country as has been the case with plague, cholera, and typhus fever.

C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, pp. 15–17.

Something changed to make smallpox a much less lethal and morbid disease with no secondary fever and little, if any, discomfort. The classic smallpox eruptions were often only a dozen or fewer. The redness usually disappeared in three or four weeks, leaving no permanent marks. In the absence of an epidemic, a case of mild smallpox was likely to be overlooked or mistaken for chicken pox.

By the time the following report was written in 1946, smallpox had all but vanished from England and the Western world. The health of people had dramatically improved. The hot regimen, bleeding and Calomel were largely no longer in medical fashion and were quickly forgotten.

“What has been the cause of the rise and fall of smallpox? Its decline in the later decades of the nineteenth century was at one time almost universally attributed to vaccination, but it is doubtful how true this is. Vaccination was never carried out with any degree of completeness, even among infants, and was maintained at a high level for a few decades only. There was therefore always a large proportion of the population unaffected by the vaccination laws. Revaccination affected only a fraction. At the present the population is largely entirely unvaccinated. Members of the public health service now flatter themselves that the cessation of such outbreaks as do occur is due to their efforts. But is this so?”

Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute, vol. 66, 1946, p. 176.

2000s

In the 2000s, Dr. Thomas Mack who had had been involved in smallpox for roughly 40 years noted that societal changes rather than universal vaccination had tamed smallpox.

“Disappearance [of smallpox] was facilitated, not impeded, by economic development. Long before the World Health Organization’s Smallpox Eradication Program began, and despite low herd immunity, unsophisticated public health facilities, and repeated introductions, smallpox disappeared from many countries as they developed economically, among them Thailand, Egypt, Mexico, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Iraq.”

Thomas Mack, MD, “A Different View of Smallpox and Vaccination,” New England Journal of Medicine, January 30, 2003, pp. 460–463.

All in all many factors have contributed to the greatly-reduced threat smallpox is today.

The discontinuation of ineffective and even dangerous treatments along with the introduction of sanitation and improved housing have all helped significantly in combatting not only smallpox but also many other communicable diseases.

For the full article, visit Roman Bystrianyk’s substack.