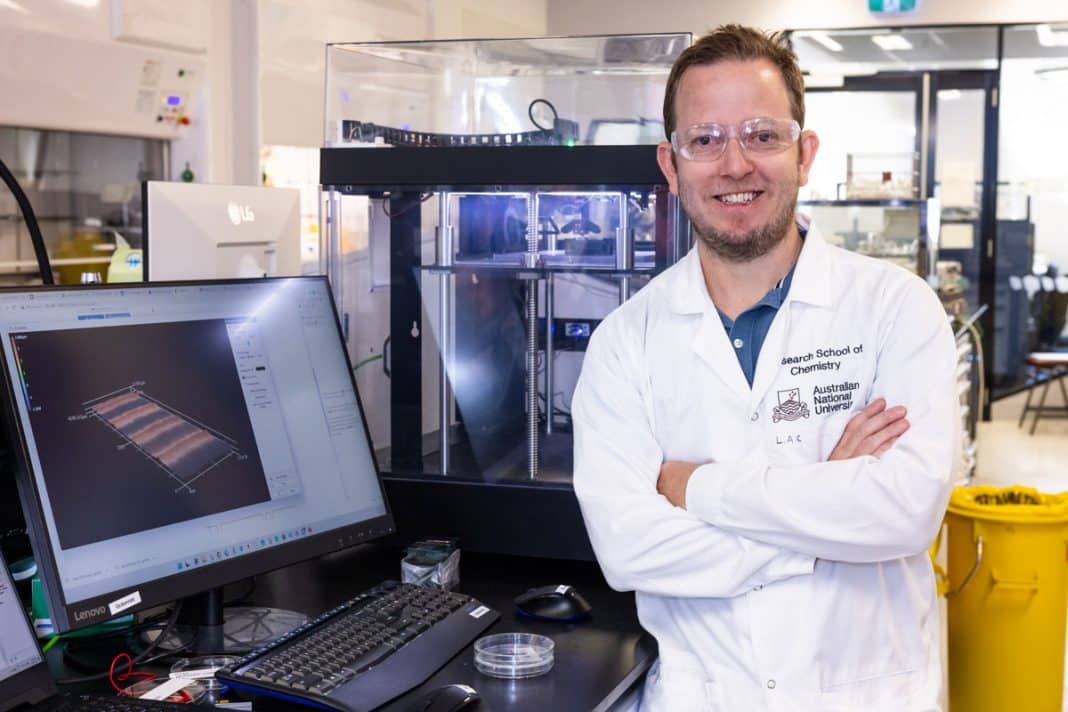

An ANU-based startup company could put Canberra on the map for 3D printing and electronics manufacturing.

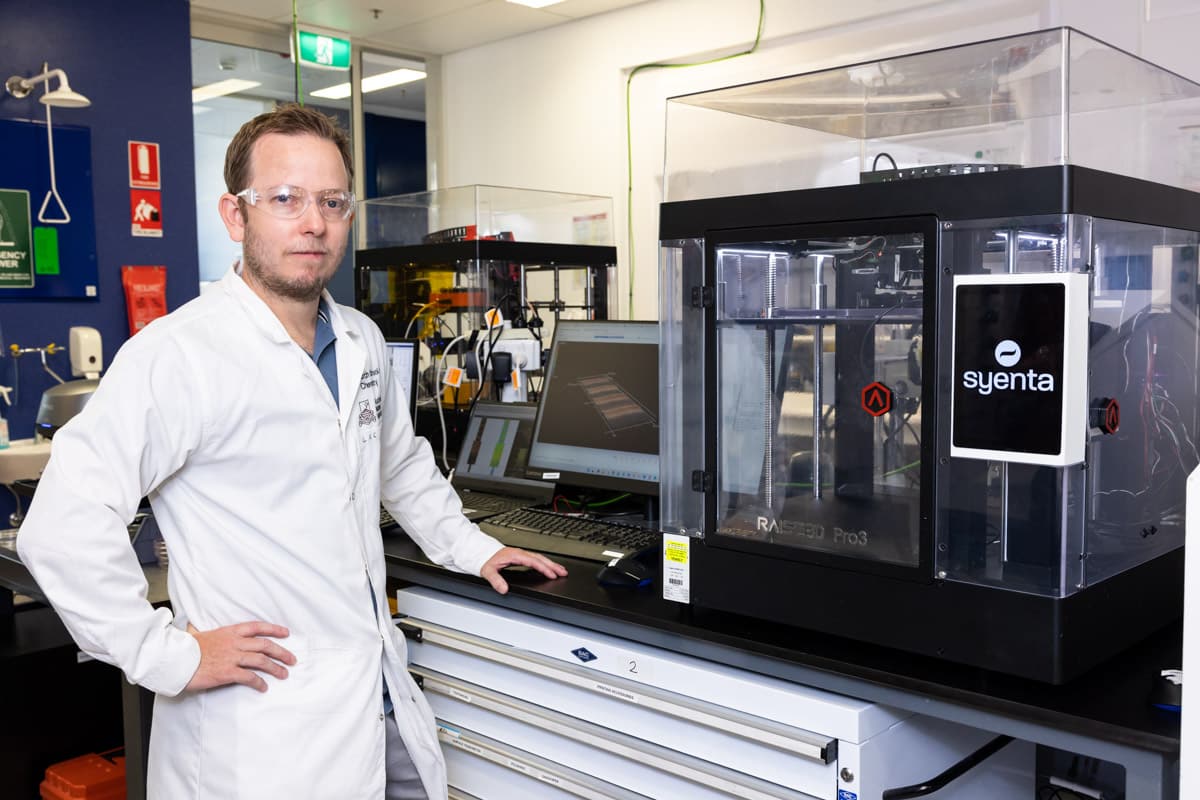

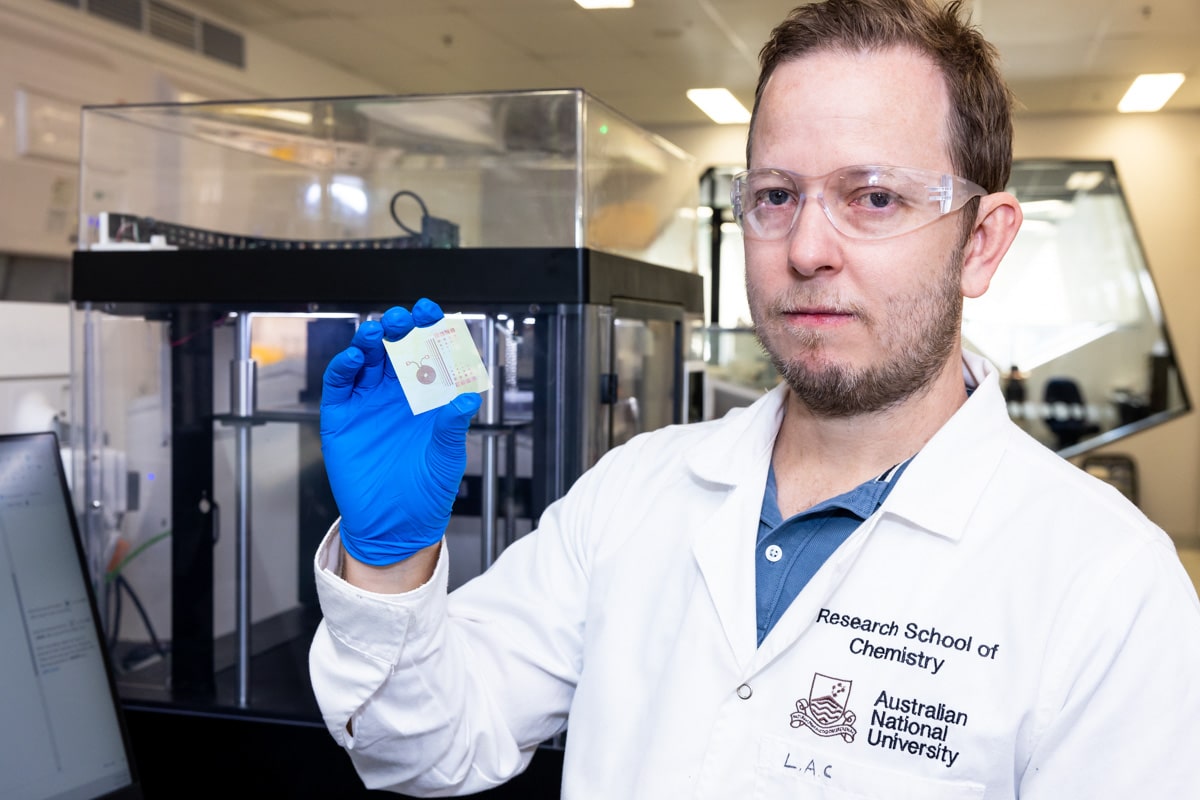

Syenta, housed in the Research School of Chemistry, declares that its multi-material electrochemical 3D printer heralds “a new era of manufacturing”, fabricating polymer, semiconductor, and metallic structures with a single device, MicroFab, at unprecedented resolution and speed.

“Most 3D printing uses heat or light to pattern plastic or material,” said cofounder Professor Luke Connal, Professor of Chemistry at ANU. “What we’re doing is quite different.”

Syenta only came out of “stealth mode” last year, but it has already interested investors and tech experts. It raised $3.7 million in seed funding from investment firm Blackbird Ventures in December, while online magazine 3DPrint.com listed it as one of the top 10 3D printing startups to watch in the world. Now, Syenta gives at least one demo a week for local or international companies. On the morning Canberra Daily visited, a group of Japanese businessmen were being given a demonstration.

Syenta began in 2020 as a late-night email chain between Professor Connal and Jekaterina Viktorova, then a PhD student, now Syenta’s CEO.

“We were always looking for new ways to print 3D things,” Professor Connal explained. “The email was around instead of heat or light, can we use electricity to 3D print? That was the start of the idea. It feels like the next day, Jeka had tested it out, and proven that it looked like it could work. From then on, it’s been three years of development.”

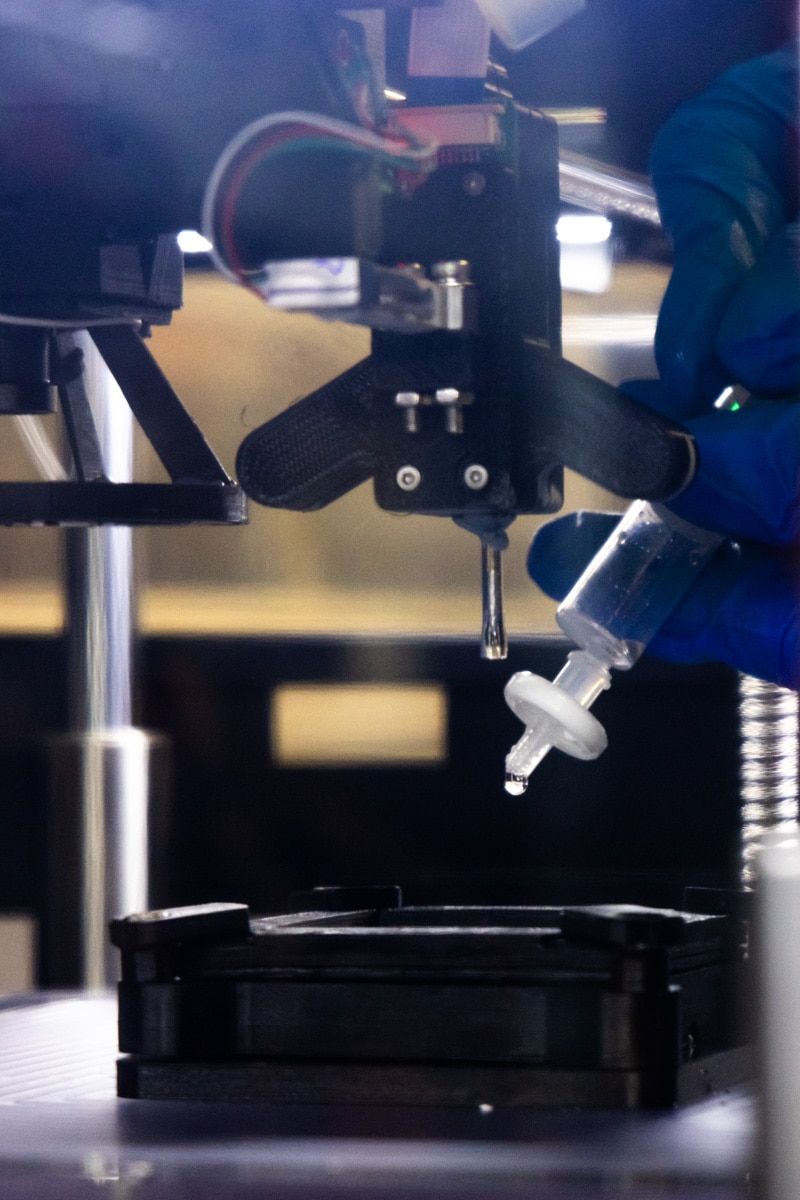

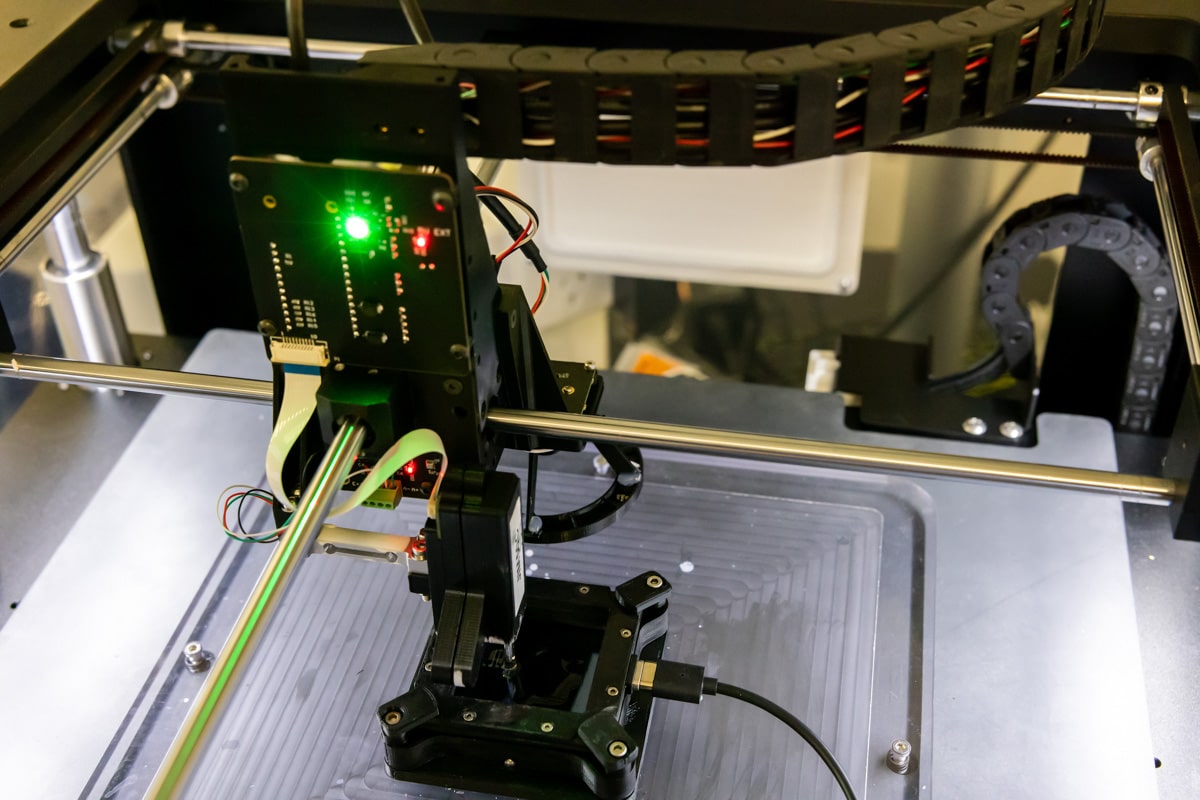

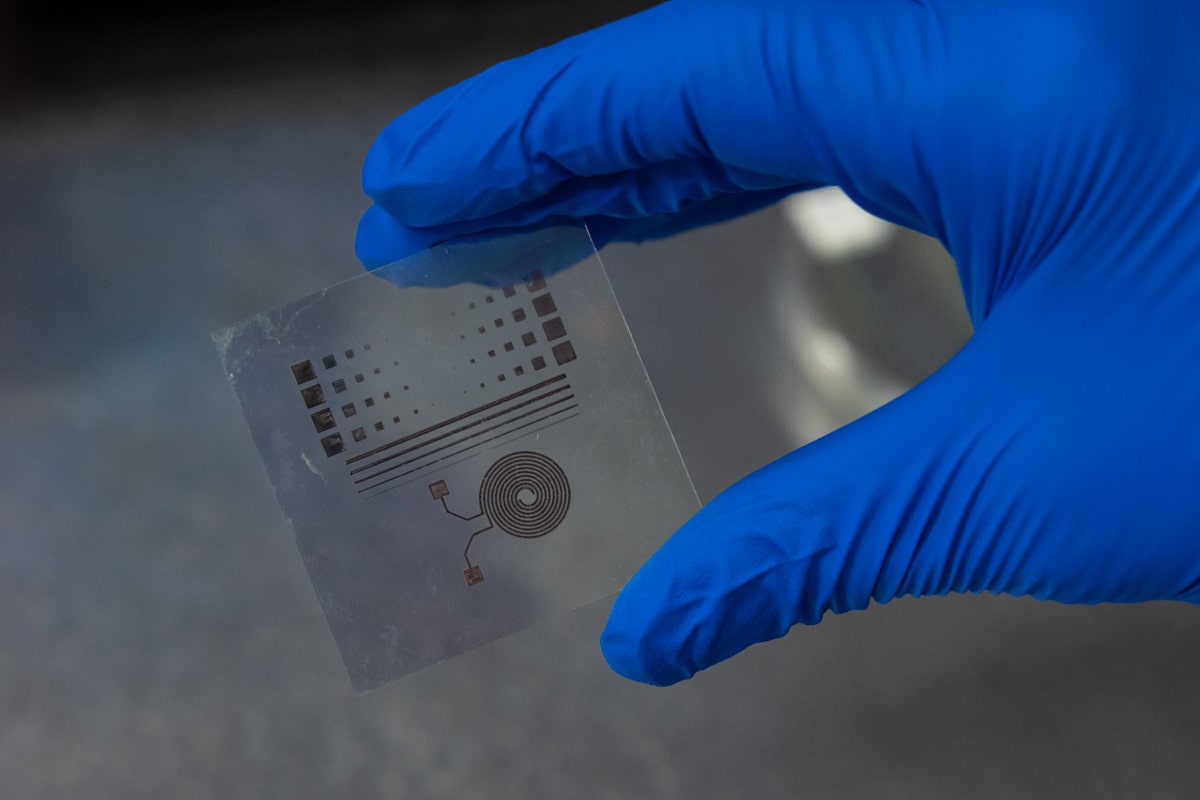

MicroFab uses electricity to solidify patterns. A small electrode provides a current and electrons to a liquid solution, producing a small-scale chemical reaction that turns a metal salt into a metal. The electrode then draws electronics with the liquid, producing the desired pattern.

The 3D printer can produce Internet of Things sensors, electrodes for photovoltaic devices and batteries, semiconductors, antennae, and printed circuit boards.

“People are printing all sorts of things,” Professor Connal said. “You don’t have a limitation, because you can just make a computer-aided design (CAD) file on your computer, and then print it … That freedom to print whatever you want … is really cool.”

First customers, such as GreatCell Energy, manufactured solar cells using copper, a cheaper material than the silver or gold they would normally use, Professor Connal said.

“It’s really quite a cheap process,” he said. “We can basically print copper cheaper than you can buy copper metal, because it comes from copper salt.”

Syenta claims its printer will democratise electronics manufacturing, allowing users to design and construct electronics from anywhere in the world, faster and cheaper, using less energy and fewer materials. 3Dprint.com predicts it could be a game changer.

“Currently,” Professor Connal said, “if you want to make some electronics, you send a design off to a fabrication centre. There’s pretty much none of those in Australia. So we have to go to either China or Europe to make those things. … They would do the print and send it back to them. … You really have to wait some time to get those back to see those designs.

“In our case, the electronic designer can have [our machine] in their workshop and essentially print their design in minutes. It really enables them to iterate quickly, and then to manufacture their optimised iteration.”

Sending printed circuit boards back and forth between countries also creates waste, but MicroFab does not waste anything at all, Professor Connal said. MicroFab’s process is additive (it electroplates materials onto a pattern), while most printed circuit board production processes are subtractive (removing unwanted parts from a copper film to form the pattern).

“It’s definitely a big waste and environmental factor in the manufacturing industry,” he said.

Syenta’s customers are also excited that their intellectual property stays in their building, Professor Connal said; designs are not sent to second parties.

“All the IP stays in house, and nothing gets shared or lost.”

MicroFab also reduces reliance on electronic supply chains, Professor Connal explained. “Being able to make things onshore … means you can just continue to make things. The economy keeps going.” He contrasts this with car manufacturing: the pandemic disrupted supply chains, causing a global shortage of semiconductors, meaning Australians waited six months for the new cars they had ordered.

Syenta has a team of 12 people – some are ANU graduates, others are from the Canberra Innovation Network (CBRIN), and a few come from outside Canberra.

Over the next two years, Professor Connal intends to grow his team, and expand into European and American markets, opening offices in different parts of the world where manufacturing happens.

“Our goal is to make sure some manufacturing is done in Australia – but the markets are in other places as well, so we need to have a presence there,” he said.

“Canberra’s home to Syenta, so we want to make sure we maintain that. Canberra is punching above its weight in startups, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Hopefully, we can add to that as well, and then build on that.”