Rumours of secret passageways linking buildings, lizard people dwellings and spy headquarters beneath Canberra have been around for decades. On a mission to dig down to the truth of what lies below our city, CD has sought to uncover some of the most mentioned theories, starting with the rumoured underground tunnels of the Australian National University.

Guiding us on this journey is senior archivist Sarah Lethbridge, who clarifies that the so-called tunnels are not tunnels at all, but a repository storing the ANU Archives. Originally constructed in 1980 as a carpark, the structure also housed university resources on its upper levels.

“Parkes Way is actually underneath us, that is the tunnel. When this space was built, the choice was either to have a road cut through the hill and split the campus, or create a cutting, place the road below and build this structure above it.

Spanning 23km, Sarah avoids using the word tunnel when she describes her workspace as it tends to raise eyebrows and spark some probing questions into what is going on down there. She says if there are any underground dwellers around, they aren’t pulling their weight doing any work or cleaning. Interestingly, the archive isn’t her first encounter with these mumblings.

“I used to work at the National Archives and there were rumours of tunnels all around the parliamentary triangle connecting buildings,” says Sarah. “Like they were a remnant of the Cold War where it was important to get from Parliament House to foreign affairs in secret.”

However, Sarah notes that tunnels connecting buildings would be practical for avoiding harsh winter winds. While secret underground workings are usually harmless and can add some fun and colour to a sometimes grey, planned city, they only become problematic if taken too seriously. Like most of us, she admits she has her favourite theory.

“The stories about ASIO occupying the top floor of a funeral parlour opposite the Russian Embassy in the early days. I hope it is true,” she smiles.

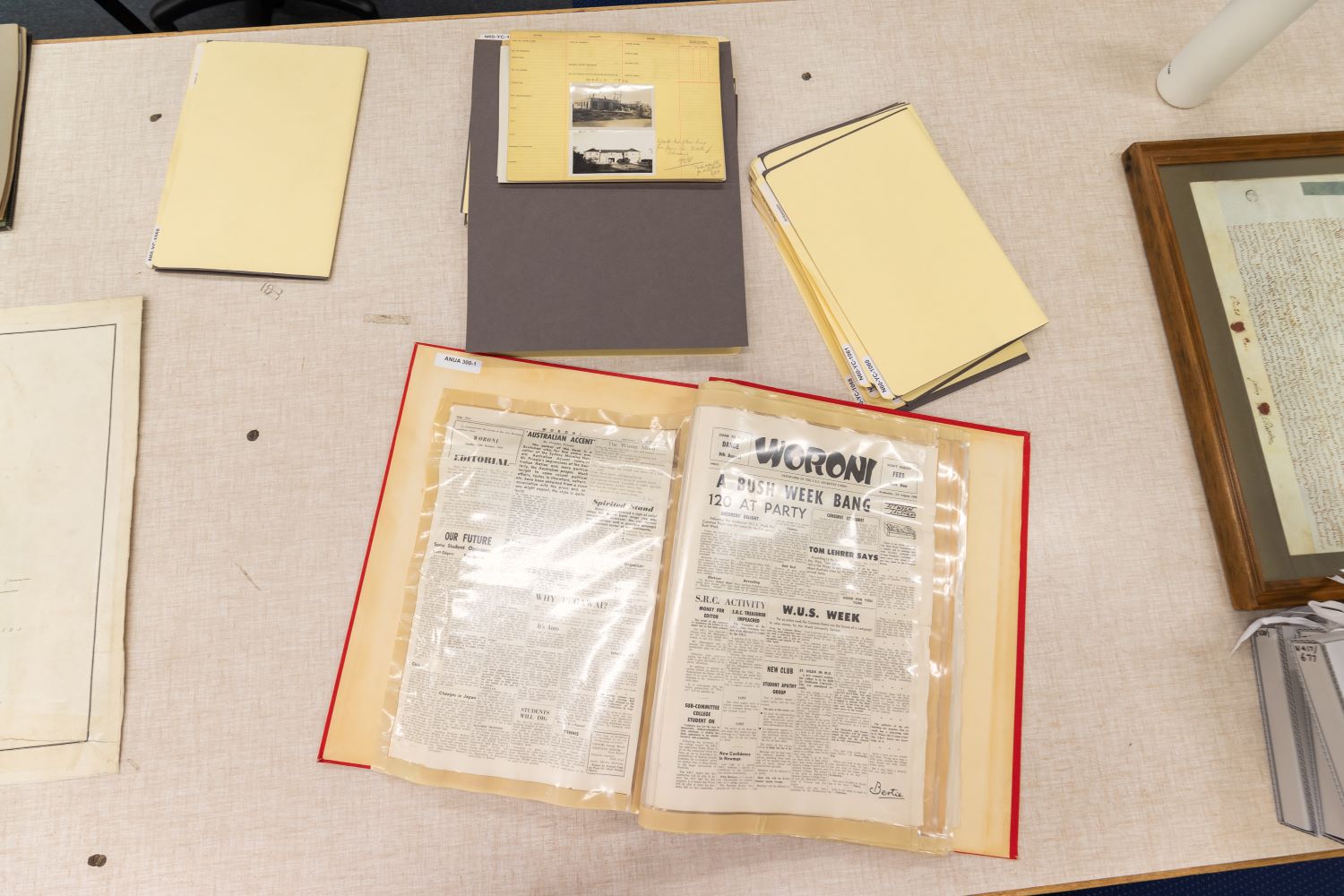

No spies are hunkering down in this bunker-like building which creates the perfect climate for storing the paper, photographs and memorabilia that fill the archives’ 23,000 shelves.

“It’s actually an excellent space for storing archives because it’s quite large, though not big enough for our entire collection. The airflow underneath and the dirt above help slow down temperature changes, which is ideal for preservation.”

What is actually in the large bunker? Sarah explains that the archive can be broken down into a few different parts. The first is the largest and the one they have been collating the longest, which began in the 1960s and is an archival history treasure chest of Australia’s 19th-century economic records.

“Our first collection was the Australian Agricultural Company, which was established in 1824 with a grant of a million acres around Port Stephens to run sheep,” says Sarah.

The collection plays a part in telling the story of business in Australia, showcasing how people communicated, how much trade came in and out, and how they dealt with difficulties. There is also an enormous amount on labour unions, including forgotten trades like bootmakers, seamstresses, and felt hat makers, who all had their own unions.

“Along with unions come records of activists, people advocating for superannuation, safer work conditions, the eight-hour day. It expanded, we’re still adding to that collection, we are still getting records of companies that are nationally significant and unions that are federally registered.”

It is easy to forget in this modern age how large big industry employers were, Sarah says they required a huge amount of manpower to operate which comes with membership records. These are particularly important because many of these workers didn’t leave a lot of written records throughout their lives.

“As a group, they’re known, individually they can disappear from history; blue-collar workers, women, Indigenous people, the disabled – people who don’t fit the mainstream can sometimes not be recorded.”

Broadening their collection in the mid-2000s, they sought records from companies who traded and worked in the Pacific region. Along with company records, Sarah says they have received donations from descendants of missionaries and colonial administrators.

These tie in well with the university’s own archives, along with council, building and policy records and building plans, they also have research from academics. Including that of people from the Pacific and our own First Nations People, Sarah says some of these groups have not survived or been widely known, nor have their languages.

“We’re much more respectful now of the peoples whose information it is, working with them to give them access and help them rebuild languages and cultures that have been diluted. It has been lost and overtaken by the dominant culture.”

The final part of the collection is a snapshot into Australia’s response to the HIV and AIDS epidemic, including public awareness information and firsthand accounts. Sarah says they have been sourced from advocates, activists, the department of health and from groups who were most likely to be impacted; homosexual men, intravenous drug users, sex workers and people living with hemophilia.

“We have a record of an activist who was on the commonwealth government taskforce. As a member, he has his own records of those activities.”

Undertaking an honours degree in history in the early 90s, Sarah graduated unsure of her next steps until she stumbled across a diploma in archives and records. This field sparked her passion for collecting and preserving information, which she saw as vital for the future. More importantly, she found fulfilment in helping people access that information, recognising the significant role archives play in preserving history and aiding research.

“Archives can really change individuals’ lives by helping them find out more about who they are, their history, and where they’ve been,” says Sarah. “It can be crucial for people to uncover information about themselves, their family, or people like them.”

Whether it be for academic research or for answers to bigger questions in life, Sarah delights in assisting the curious to find their answers.

“Sometimes it’s ‘That’s nice’. Sometimes, like the elderly lady who came to see us when I was in Melbourne wanting to know why her mother was made a ward of the state, she said ‘Thank you that has answered a lot of questions’.”

Who can access the information stored in the archives? Sarah says they are happy to share the information with people who aren’t connected with ANU such as researchers, family historians, PhD students, film makers and even architects.

As they store so much information and it is not stored by subject, Sarah suggests that you come in with a question you want answered in mind.

“You start by talking to your friendly archivists about your question and we work with you to find records if they exist,” she smiles.

The archive welcomes inquiries, Sarah says even if they aren’t the people who can help, they will often be able to direct you to the right archive or history society. You contact the archives via email; [email protected]