Scientists from the Australian National University (ANU) have identified a gene that is responsible for causing lupus, an autoimmune disease that can be life-threatening in severe cases.

This is the first time researchers have identified the TLR7 gene, in its mutated form, causes lupus.

The discovery, made by an international team of scientists, could pave the way for new and more effective treatments, but without the side-effects associated with current approaches, which often leave patients more susceptible to infection, and can lower their quality of life.

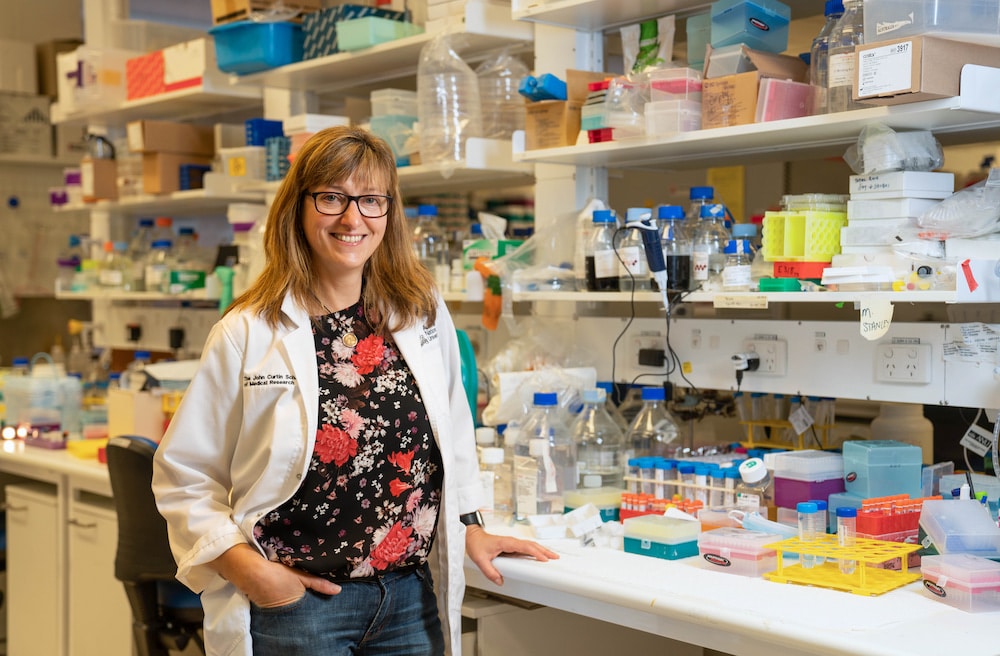

“This raises the exciting possibility of developing new drugs targeting TLR7, potentially revolutionising treatments for lupus,” said senior author Dr Vicki Athanasopoulos, from the ANU John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR).

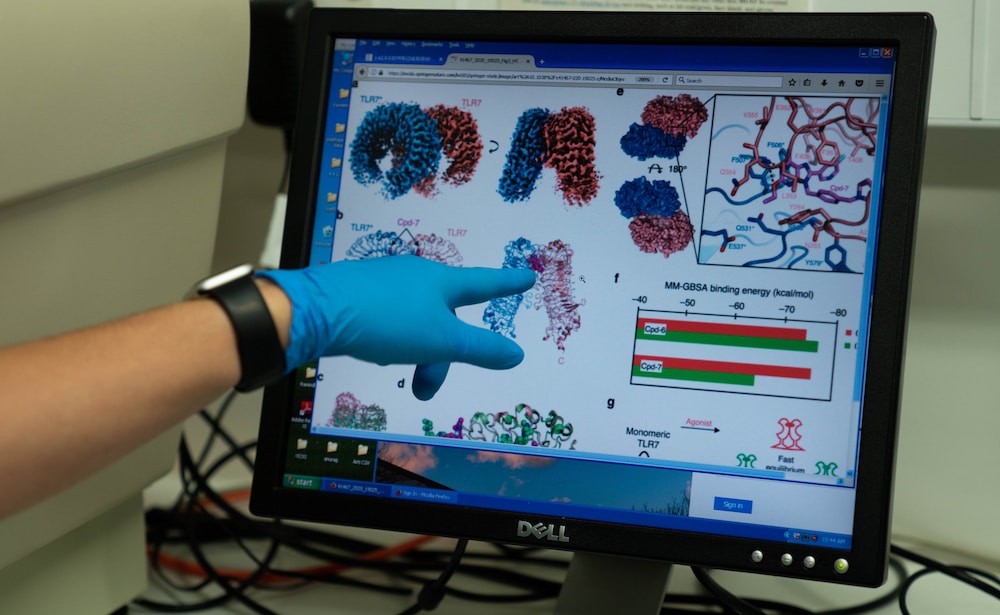

The gene TLR7 is programmed to help the immune system guard against viral infections, but in its mutated form it can become aggressive and cause the immune system to attack healthy cells.

There is currently no cure for lupus, a disease that is estimated to affect nine times more women than men. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe, and can include inflammation in organs and joints, impacted movement, skin rashes, and fatigue. In extreme cases, complications can be fatal.

The TLR7 mutation was first discovered in a young Spanish girl called Gabriela, who was diagnosed with lupus when she was seven years old.

Using a gene-editing tool, the researchers introduced the human-derived mutation into mice to study whether the disease developed in the rodents, explained PhD scholar Grant Brown.

Mice carrying the mutant TLR7 protein developed a condition that mimicked severe autoimmune disease in human patients, providing evidence that the TLR7 mutation causes lupus.

While there is no cure for lupus, the researchers hope this discovery could lead to more tailored lupus treatments that directly target the TLR7 gene, which in turn could help patients better manage their condition.

The researchers are working with pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs or tweak existing ones to explicitly target the TLR7 gene and other proteins acting in the same biochemical pathway to the TLR7 protein.

Other systemic autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis and dermatomyositis, fit within the same broad family as lupus, and TLR7 may play a role in these conditions, believes senior author Professor Carola Vinuesa, from the ANU Centre for Personalised Immunology and the Francis Crick Institute in the UK.

The research findings may also help explain why women are nine times more likely to develop lupus compared to men. TLR7 is present in the X chromosome, and women have two X chromosomes and two copies of the TLR7 gene. By comparison, men only have one X chromosome.

“This means females with an overactive TLR7 gene can have two functioning copies, potentially doubling the harm,” Professor Vinuesa said.