To anyone fascinated by the ancient world, the ANU Classics Museum is a treasure trove indeed.

The collection spans more than 1,500 years, from Bronze Age Minoan Crete and the glory that was Greece to the Roman empire at its height and its fall in the fifth century.

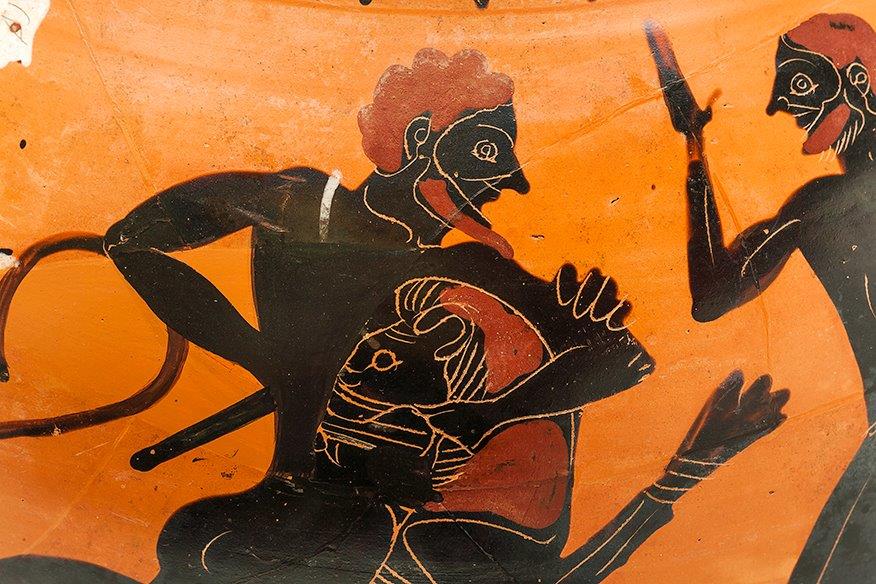

Among its more than 600 items are coins and busts of Roman emperors and Greek tyrants, mosaics from Pompeii and Herculaneum, cursed tombstones, exquisite vases depicting the Labours of Heracles, goat’s-headed vases, and a magnificent scale model of the Eternal City.

We tend, perhaps, to think of the Classical world as epic and mythical; Greece is an idyllic, harmonious Arcadian landscape of beauty and light, but also full of gods, monsters, and sublime tragedy; Rome a political drama of mad emperors, conspiracy, treachery, and murder.

But the ANU museum focuses on the everyday, reminding us how little human nature has changed in two millennia.

The museum celebrates its 60th anniversary next year; it was founded in 1962 by Richard Johnson, ANU’s first professor of classics. At the time, curator Elizabeth Minchin explains, hardly anyone travelled; Classics students wouldn’t have been able to visit the British Museum or the Louvre, so the solution was to create a museum.

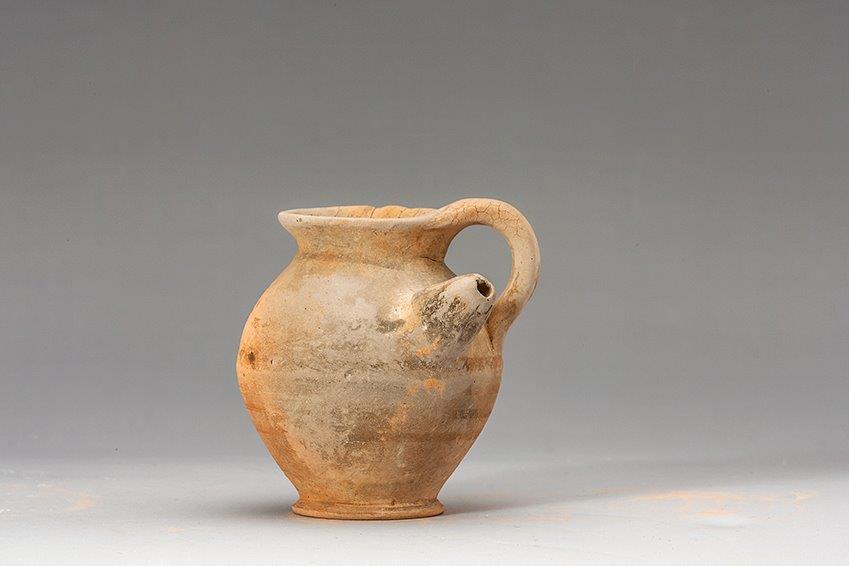

The collection began with only two items: an 8th century BC mug (2,800 years old) and an oil container depicting Heracles retrieving the girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta.

“They’re quite modest items, and it was a very modest beginning,” Professor Minchin said.

Since then, the museum has grown, steadily purchasing an item or two a year. Some items come from the ANU’s archaeological excavations in Syria. The British Museum donated a few cups, and some Bronze Age items are on loan from the National Gallery.

“Because the museum started in the 1960s and not the 1860s, we haven’t got grand items from Egypt and large pots from Southern Italy; we’ve acquired slowly and painfully items that are relevant to teaching, but items that are small-scale and domestic rather than showpieces,” Professor Minchin said.

But those small-scale, domestic items illuminate social life in ways that grander items perhaps cannot. “You look at big pots and you think those big pots were big pots for a burial, and that’s it.” But the ANU’s collection shows not how people died, but how they lived.

Here are baby feeding-bottles used by mothers and nurses; oil jars and strigils (scrapers) people took to the baths in the days before soap was invented; wine vessels from Athenian drinking parties; glass amphorae; weights women used weaving at the loom, or measuring goods in the marketplace; jewellery, brass mirrors, dice, and surgical instruments; and sieves used to strain cheese.

“It’s the homeliness of things that works quite well,” Professor Minchin said. “It’s relatable in a way that a lot of the grand museums aren’t.”

And students can handle those items. “There’s nothing quite like holding Ancient World things! Students are breathing the same air as the items inside, turning them over, finding the fingerprints of the potter on the underside. That’s magic.”

One of Professor Minchin’s favourite items is a bronze figure of the Greek goddess Aphrodite rising from the waves and wringing out her hair, “a very sexy, relaxed pose”. Less sexy but equally striking is a jug in the form of a wrinkled old woman clutching a wine jar. In the same case, a winged Nike records the names of Olympian victors on a tablet.

In a world without paper, wax tablets were used for everyday purposes, Professor Minchin explains; once they had read the message, people could scrape it out and write something new. One tablet in the collection was a schoolchild’s exercise book, copying out some important saying. There is also a rare papyrus, preserved in the arid heat of Egypt. But papyrus was expensive; much cheaper were broken pieces of pottery (ostraca). The Athenians used them to expel too-prominent citizens for a decade – among them the general Themistocles, who defeated the Persians at the naval battle of Salamis, and the statesmen Cimon and Aristides – but the ostracon in the ANU’s collection is a simple receipt for bath tax.

Some of the most touching items were found in burial sites: a child’s sarcophagus; a cinerary urn for a toddler; a set of almost Art Nouveau pottery purchased for a daughter’s wedding dowry, but never used; a devoted son’s funerary inscription to his mother. A Greek grave stele commemorates Maxima, “the sweetest and wisest woman, ladylike devoted to her husband”; she is shown with her mirror and tablet. But it also warns desecrators: “Whoever mutilates this grave stele, may he bury his children before their time.” A lot of grave steles had this sort of threat, Professor Minchin explains, to stop people scraping off inscriptions and putting new ones on.

The ancient world – whether Mediterranean, Indian, or Chinese – gives you a perspective on today, Professor Minchin believes.

It is also important to know about the origins of democracy in 5th century Athens, and to know the myths that are simply part of Western culture, and which remain part of a very strong cultural thread in Australia. “They’re touchstones for values and behaviours, and for understanding a certain cultural mindset.”

Nor is cancel culture anything new; protesters remove the statues of Cecil Rhodes or Civil War generals, just as the Romans tore down statues of hated emperors like Domitian and struck their names from the public record.

Her field is the Homeric epic; her current research is into boasting, blaming, thanking, and apologising in the great poems. “The poet of The Iliad obviously understood human nature in a very sophisticated way.” Today’s politicians boast and blame as much as any Greek hero. “Every day on the news, I hear examples of boasting and blaming – and not much apologising. And I think what happened in The Iliad is happening here in my own life.”

The ANU Classics Museum (A.D. Hope Building) is open 9am to 4pm on weekdays (except public holidays and during lockdown).

Volunteer guides run tours of the ANU Classics Museum on the second Friday of every month. Schools and other groups can also book tours.

The full catalogue is online. There is also an app sampling items from the collection, available from the Apple App Store or Google Play.

Get all the latest Canberra news, sport, entertainment, lifestyle, competitions and more delivered straight to your inbox with the Canberra Daily Daily Newsletter. Sign up here.