National capability — and you might also say, national character — can be revealed in a crisis. So, what has COVID-19 taught us about Australia?

It has taught us, amid many examples of failed leadership across the world, that Australia possesses a strong capacity for effective action in times of need.

Our leaders and people have been able to act with bipartisan unity. Our expert institutions, including our public health bodies, have proved generally up to the task of protecting our people.

And government has been prepared to take significant measures to avoid a catastrophic economic downturn.

A return to isolation and protectionism

As for the national character, the picture is more mixed.

The pandemic has certainly illustrated the limits of any mythological notion of “Australianness”.

Despite our celebration of larrikinism, the pandemic has demonstrated we are a compliant people when it comes to taking orders from authorities – though this has arguably helped in ensuring high levels of adherence to public health orders.

Nor has the pandemic demonstrated a clear triumph of Australian egalitarianism and the fair go. There were times when we’ve resembled an individualistic rabble, what with the widespread hoarding of supplies in the early stages of the pandemic. A fair go wasn’t necessarily extended to Asian Australians, who have experienced a significant spike in racism during this pandemic.

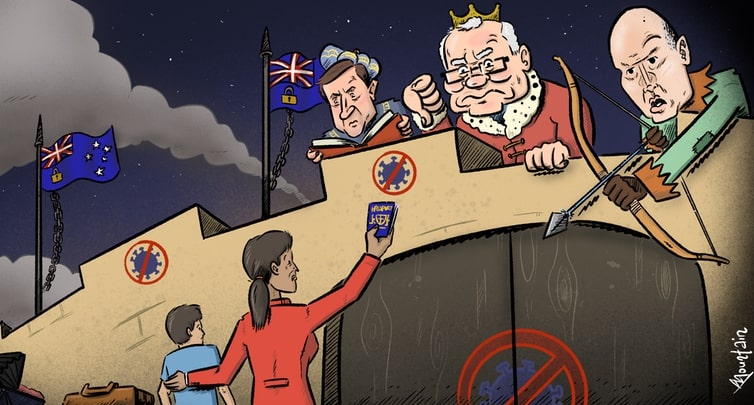

One historic aspect of the national character, though, has indisputably come to the fore. We’ve seen a return of a “Fortress Australia” mentality. This sees Australia as an island nation forever beset by threats from outside, whether it’s people or pathogens.

For many Australians, there is nothing bad at all with having national borders closed indefinitely. We shouldn’t rush to re-engage with the world, not when there’s a deadly virus in circulation.

National isolation is seen as a fair price to ensure the country stays “safe”. People who journey beyond our shores to be with their loved ones as they die or reunite with their partners and children are castigated for putting us all at risk.

Read more: ‘Fortress Australia’: what are the costs of closing ourselves off to the world?

Moving away from fear towards recovery

That’s one way to look at COVID-19. But, for the past six months, as part of a collaborative taskforce examining how Australia should respond to COVID-19, we have been exploring an alternative to Fortress Australia.

There should be no false choice between remaining closed or open: modern Australia simply can’t exist in parochial isolation. Our economy depends on trade and immigration. Our society and culture are deeply connected to the rest of the world. The majority of Australians were either born overseas or have a parent who was.

However, this version of Australia is now being put at risk by the prospect of an indefinite extension of our closed borders, and by some national politicians who revel in the protectionism it invites.

We believe the urgency Australia showed in initially suppressing and then locally eliminating COVID-19 now needs to be shown towards preparing the country to reopen to the rest of the world.

If Australia isn’t ready to reopen effectively when the world recovers from the worst of the pandemic, we will face enormous social dislocation and prolonged economic pain. We need to move from fear and anxiety to a more confident stance of national recovery. Otherwise, we will be left behind as a hermit nation.

Indeed, we can’t do as some suggest — only open up when zero COVID transmissions can be guaranteed. The reason is simple, and it’s based on the science. The virus causing COVID-19 (SARS CoV-2) will not disappear from the world. We need to acknowledge and respond to this reality.

Here’s a more realistic and sensible option: we need a plan to re-open Australia to the world in a controlled, risk-weighted and staged manner. This would prevent any large outbreaks associated with an excessive burden on the health care system or loss of life.

In some respects, Australia has already proven it can do this. Since the emergence of COVID-19, some 250,000 people (citizens, permanent residents and short-term visitors) have arrived on our shores. And cases have been kept to a minimum, despite the creakiness of hotel quarantine.

A five-step roadmap for reopening

We provide the following roadmap for Australia to reopen to the world. Australia needs to pursue:

- a comprehensive and successful vaccination program

- pilot programs for re-opening prior to the conclusion of the vaccination program to support industries critical to Australia’s economy, including tourism and the creative industries, horticultural farming and international education

- a certification scheme, across these programs, which permits only those with documented vaccination and/or SARS CoV-2 immunity to enter Australia or travel overseas

- improved border protection measures involving rapid testing on arrival

- a new range of new risk-weighted quarantine measures, complementing the maintenance of hotel quarantine for those who come from high-risk countries, refuse testing or test positive on arrival.

If Australia were to pursue this, it would be in a strong position to restore its immigration program to its pre-COVID levels by 2022-23, assuming the continuing suppression of the virus.

This challenge is a long way from the comforts of a retreat to Fortress Australia. But it’s necessary – at least if we want to remain a country that is engaged with the world.

One thing, though, is clear. Reopening requires not only building a path towards rapid large-scale vaccination of the Australian population and changes to our quarantine system, it requires the urgent building of a “psychological runway” for reopening. We need Australians to be mentally ready for re-engagement.

Yes, we can take pride in how Australia has been winning the “war” against COVID-19. But it’s time now for us to start thinking about winning the “peace”.

Tim Soutphommasane, Professor of Practice (Sociology and Political Theory) Director, Culture Strategy, University of Sydney and Marc Stears, Professor and Director, Sydney Policy Lab, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.