Aboriginal advocates, environmentalists, and the ACT Greens have urged the NSW Government to alter their plans for the Barton Highway duplication, fearing it will ruin culturally significant sites, endangered trees, and habitat for native animals.

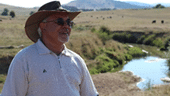

“There’s no way in the world that we want to stop the duplication itself,” said Wally Bell, chair and cultural heritage officer of the Buru Ngunawal Aboriginal Corporation. “We just want to have a more viable way of doing it, and to try to protect our culture at the same time.”

Transport for NSW’s $200 million upgrade of the Barton Highway includes duplicating an 8km stretch from Hall to Murrumbateman.

Mr Bell believes the duplication will damage or destroy ring trees and a ‘spirit circle’ of trees near the ACT/NSW border Aboriginal people used as landmarks and camping sites for generations.

The Ginninderra Catchment Group (of which Mr Bell is a member) are concerned about the preservation of Aboriginal heritage sites throughout the proposed location. They also worry the road works will clear areas of critically endangered box gum grassy woodland that are home to sugar gliders.

Mr Bell, the GCG, and local Aboriginal representatives have been in consultation with the NSW Government on this issue for more then a decade, said GCG executive officer Kathryn McGilp.

“Even despite that extensive consultation process, the fact that we still find ourselves here at the end of the line is less than ideal,” Ms McGilp said. “The fact that within those 10 years, they have still not been able to come up with a solution that significantly reduces these impacts is disappointing.”

Mr Bell’s cultural heritage assessment (on-foot survey) of the proposed duplication works uncovered cultural features like scar trees, ring trees, and artefact scatter sites (where Aboriginal people made stone tools).

Transport for NSW’s original design would have removed the ring trees altogether. Ms McGilp acknowledged the current Barton Highway footprint limited the destruction to some of those heritage and ecological areas, but said there was definitely significant room for improvement.

“With some minor alterations to the proposed road alignment, we can save all of these features,” Ms McGilp said.

As matters stand, Mr Bell doubts the trees will survive. The ring trees at the border will now be on a median strip between two carriageways.

A gully line provides moisture for the trees, but the carriageway will redirect run-off and moisture away from the tree roots, while exhaust fumes from the highway will also be hazardous to their health.

Those trees were once a way for Aboriginal people to navigate through country, similar to street signs today, Mr Bell explained.

The duplication works could also destroy a ‘spirit circle’ of trees on Kaveneys Road, which joins up with the Barton Highway.

The naturally formed circle of trees was used as a campsite by Aboriginal people; when travelling from Yass to the Canberra region, Mr Bell explained, his ancestors would light fire, hold a smoking ceremony to cleanse the site of bad spirits, and camp overnight in safety.

Mr Bell did not have access to this site until March, after works had begun. The landowner did not want highway works going through her property, and denied access to carry out the assessment, he said.

Mr Bell and the Ginninderry Catchment Group believe the Barton Highway should be redirected to the east, or the current road widened.

A Landcare member, an engineering expert, has developed a feasible proposed alternative alignment – a minor alteration to the road curvature – that meets NSW road guidelines, Ms McGilp said. As part of his cultural heritage assessment, Mr Bell conducted a survey on the eastern side of the Barton Highway, and believes there is room to move to the east.

The Ginninderry Catchment Group, Onerwal Land Council, the Yass Area Network of Landcare Groups, and the Friends of Grasslands started a petition last week for a revised environmental assessment and a review of their proposed road alignment.

Mr Bell, the GCG, and the petitioners have tried to negotiate with the Barton Highway Upgrade Alliance – comprising Transport for NSW, Seymour Whyte Constructions, and SMEC. But they say the BHUA do not want to change their design plan, and will not consider any alternative.

“They’ve got the plan design already approved, and they don’t want to deviate from it,” Mr Bell said. “It’s not beyond their capability to do it; at the moment, they’re refusing to do it.”

Transport for NSW said it took its obligations to the environment and the local environment seriously, and was working with local Aboriginal community groups on upgrade plans for the Barton Highway, a spokesperson said.

They have paused work near the Kavenys Road grove while they carry out investigations out and they consider their next steps.

Consultation with Registered Aboriginal Parties, archaeologists, and other specialists on cultural heritage will continue into the weekend, the Transport for NSW spokesperson said.

Transport for NSW will provide more information to the community when an outcome has been reached.

But the fate of these Aboriginal sites near the Barton Highway is part of the bigger question of the loss of Australia’s Aboriginal heritage.

European occupation has already destroyed a lot of cultural heritage, Mr Bell said; he wants to keep and maintain the remnant ring trees and spirit circles.

“We’re really trying to save as much as we can, because we have lost so much already.”

That, he said, is a difficult task when groups like the BHUA do not understand Aboriginal culture or how it relates to the land. The ‘spirit circle’ is intangible; there is no physical evidence – the trees have not been scarred or carved – but cultural knowledge of the site has been handed down for generations by people travelling through.

Rebecca Vassarotti, ACT Minister for the Environment, urged her NSW counterparts to adequately protect the tree sites.

“It is vital that First Nation cultural heritage is not destroyed without other options being assessed,” she wrote.

Dr Tjanara Goreng Goreng, ACT Greens Senate candidate and Wakka Wakka woman, is also concerned.

“This can’t keep happening,” she said. “Time and again, we are seeing state governments completely disregard First Nations cultural heritage.”

Dr Goreng Goreng said the NSW provisions for First Nations cultural heritage were outdated, ineffective, and under review. NSW is the only state without stand-alone Aboriginal cultural heritage legislation; instead, most NSW cultural heritage is protected and managed under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, which Aboriginal people feel does not give them enough say over the management of their heritage.

“Be it the sacred Djab Wurrung trees in Victoria or the design of this road, in both instances, it wouldn’t even be difficult to make sure the road goes around these sacred sites, but the NSW, Victorian and Federal governments, and their relative transport and roads departments, simply don’t care. This shows how far we have to go to build a society that respects First Nations sovereignty, heritage, and culture.”