Conductor Benjamin Bayl considers Jean-Philippe Rameau the greatest composer of dance music until Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky. “A fairly bold claim to make,” he admits – but Canberra audiences will have the chance to hear the 18th century Frenchman’s music in a CSO concert next week.

Miracles in the Age of Reason, on Wednesday and Thursday nights, 18-19 May, should be a stellar concert. It also features a flute concerto by C.P.E. Bach, written for Frederick the Great – and played by Emma Sholl on a 14-carat rose gold Burkart flute; one of Mozart’s last and greatest symphonies; and, as a counterpoint, a piece by 20th century Australian composer Richard Meale.

“What ties all these four works together is that all the composers diverge from the status quo somehow,” Bayl, who has flown out from Germany to conduct the concert, explained. “They challenge the norms of other composers, or of formal expectations, or the way that things should be, or could be, done.

“All these composers had a knack of writing with an original voice, of being able to use structure to their advantage, to be so adept at composition that they were able to take the road less travelled and succeed.”

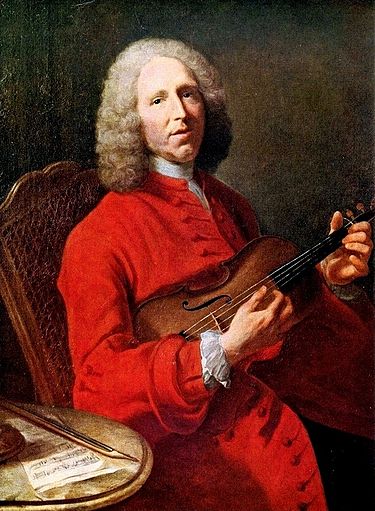

Rameau was the first composer ever described as ‘baroque’, a term applied now to music of the early 18th century. It was a criticism: Rameau’s music was too new and too different. The organist and musical theorist wrote his first opera when he was 50.

“The brilliance of his music,” Bayl said, “comes from the fact that he knew so much about harmony and melody, that somehow, when the time came to compose, he knew how to break all the rules and be original. Even at the time, Rameau’s music was not accepted immediately, because it was regarded as just so out there.”

Hippolyte et Aricie (1733) struck Paris like a thunderbolt, and divided music lovers into “two violently extreme parties, enraged against each other”, one contemporary wrote: the progressive supporters of Rameau (the ramistes or ramoneurs) and the conservative lullistes, who preferred the 17th-century operas of Lully. “The older and the newer music was for each of them a kind of religion for which they took up arms.”

There was too much music, too much harmony, too much learning, too much everything in Hippolyte, some contemporaries felt – used as they were to Lully’s rather stilted works, with their formulaic plots and music, and bootlicking prologues praising Louis XIV as the greatest hero who ever lived, the equal of various Roman gods. Rameau himself considered Lully his master and guide, but, a later critic wrote, “it was the art of Lully with a very great advance in musical richness, variety, suppleness, and colour”.

Listeners were amazed by the new and surprising harmonies and innovative instrumentation, including the extraordinary, enharmonic Trio of the Fates. “There’s enough music to make ten operas,” exclaimed the composer André Campra; “this man will eclipse us all.” And the great writer Voltaire hailed Rameau as the greatest musician in France, “our Euclid-Orpheus”. Twenty-odd operas followed, of which the best known is Les Indes galantes, something like a Broadway revue, with the delightful Grand Calumet de la Paix (based on a Native American dance).

In next week’s concert, Rameau is represented by a suite of dances from his later opera Platée (1745), a grotesque comedy about a vain, toad-like swamp nymph who believes Jupiter has fallen in love with her – “A particularly irreverent piece as opposed to all the serious tragedies of French opera at the time,” Bayl said. “It’s not a story you would expect from a Louis XIV-type world at all. He’s already a composer who dared to write with his tongue in cheek.”

The dances themselves exhibit elegance and playfulness, sophistication and irreverence, and end with a storm scene.

“He seems effortlessly to be able to constantly reinvent all the different dance forms from the earlier French Baroque. Gavotte or bourrée, sarabande, passepied, or gigue, there’s no two alike. … The rhythmic and harmonic daring that he manages to put into them is something which certainly no other composer of that time was able to match. Nobody springs to mind between then and the great Russian ballets of the 19th and 20th centuries… It’s almost unbelievable to think Rameau wrote this music in the 1740s, because it sounds to my ears very modern with the musical risks that he takes.”

While there are plenty of violin and oboe concertos, flute concertos from the 18th century are unusual, Bayl notes. C.P.E. Bach (1714–88), son of the great Johann Sebastian, wrote his Flute Concerto in D minor for Frederick the Great, King of Prussia. The monarch was a noted flute player – but even he found it challenging. The Sturm und Drang third movement (allegro di molto) work is “very fast and furious, and incredibly virtuosic for the flute”, Bayl said – but the andante second movement, however, could almost be an opera aria in its placid beauty.

“[C.P.E. Bach] is another composer with an incredible musical pedigree and education, but still managed to break from the mould, and develop a very original voice in early classical music. He’s a bridge between the Baroque and classical styles.”

Richard Meale’s Cantilena Pacifica belongs squarely to the 20th century: a peaceful song written for the death of his best friend from cancer. Meale recalled that its emotional truth marked a departure from his earlier avant-garde style.

“Lots of Meale’s early works were much more atonal and experimental,” Bayl said. “In this one, he almost comes back to a simpler, clearer musical language.”

The work was a late substitution; originally, Bayl planned to conduct Meale’s Lumen, a chamber piece that fit more into the Enlightenment theme, but there was no orchestral version.

“It’s good to have an Australian work in the program, and there weren’t many Australian works from the 1780s to choose from!”

The concert concludes with Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 in E-flat (1788); one of his three last symphonies, it takes a turn towards more experimental ideas, instrumentation, and harmony, Bayl argues.

The “very grand, noble” first movement (Adagio – Allegro) could almost be the overture of an opera, while the second movement (Andante con moto) starts in very simple, almost teasing short phrases, then goes through the most tortured harmonic sequences in the middle.

““You never quite know where the harmonies are going to end up,” Bayl said. “It’s like he goes through every possible key before he stops himself. I think that’s kind of cool.”

Mozart ditches the oboes in favour of the clarinet – then a relatively new instrument – for the third movement’s Trio, while the fourth movement (Allegro) ends suddenly, without the expected coda.

“The mark of a composer who is extremely confident in his skills, and loves to tease or surprise his audiences.” Many of whom, in those days, were seldom attentive: “They were often sitting in their boxes, having a drink or some food – or heaven knows what else! Sometimes, the performance on the stage might have taken second place.”

Not that there’s any danger of that in the CSO’s concert, with such a feast of innovative music.

CSO presents Llewellyn Series: Miracles in the Age of Reason, on 18-19 May 7.30pm, Llewellyn Hall, ANU School of Music. Tickets: cso.org.au.