For ufologists the US government’s eagerly anticipated report of “unidentified aerial phenomena” may be a major disappointment. It goes further than any previous report in admitting unknowns. But conspiracy theorists will likely dismiss it as a cover-up.

But they aren’t alone in tending to dismiss anything that jars with their accepted narrative.

Take the “lab leak theory”. In January, for example, the Washington Post not only called the idea that COVID-19 was man-made a “debunked fringe theory”. It also called the theory it originated from the Wuhan Institute of Virology a “disputed fringe theory”.

Facebook banned claims the virus was made in a lab for being false and debunked in February. It has now reversed that ruling, with US president Joe Biden ordering his intelligence experts to “bring us closer to a definitive conclusion” by the end of August.

The issue has been complicated by hyper-partisan media conflating Facebook’s ban with censorship of the lab-leak theory. But many also dismissed the lab-leak theory too easily by conflating it with other conspiracy theories.

Read more: The COVID-19 lab-leak hypothesis is plausible because accidents happen. I should know

We’re all prone to accepting one narrative and sticking to it, no matter the evidence. This problem isn’t just “out there”. Behavioural research offers some lessons for all us to keep front and centre.

Seeing what we want to see

Even if we pride ourselves on being independently minded we can still fall prey to cognitive biases.

Part of this is due to overconfidence in our own decision-making skills.

This isn’t just the result of the phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect – in which we tend to overestimate our competence in areas in which we are incompetent. Highly intelligent people are also susceptible to believing highly irrational ideas, as demonstrated by the list of Nobel prize-winning scientists who have embraced scientifically questionable beliefs.

Part of it also has to do with believing what we want to be true.

We settle on most of our opinions through nothing better than snap judgement or instincts. Our internal “press secretary” – a mental module that convinces us of our own infallibility – then justifies our reasons for holding those opinions after the fact.

Behavioural scientists call this motivated reasoning – when your personal preferences cloud your grasp on reality.

As Malcolm Gladwell writes in his book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (Little, Brown, 2005): “Our selection decisions are a good deal less rational than we think.”

How long is a piece of string? You tell me

One cognitive bias that is especially amplified by social media is good old-fashioned conformism.

The potency of conformist thinking was graphically demonstrated by psychologist Solomon Asch in his classic 1956 study showing we can even disregard the evidence of our own eyes when it contradicts the majority view.

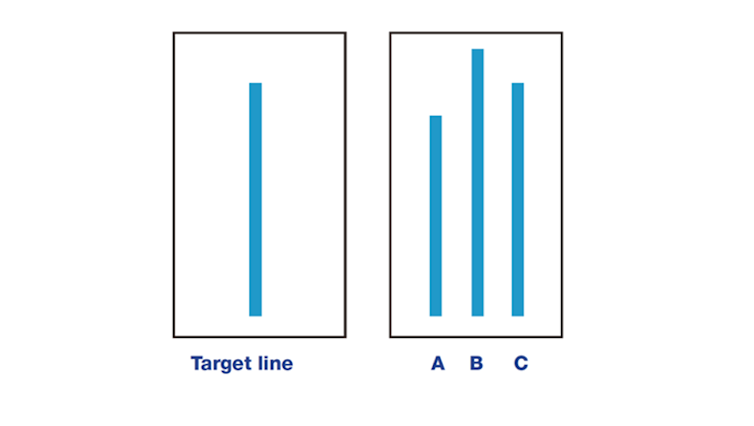

Asch assembled groups of participants and had them judge which of three numbered lines had the same length as a target line.

Which numbered line is the same length as the one on the left? The answer should be easy. But in Asch’s group only one person was a real participant. The six others were “stooges”, instructed to sometimes give the same, patently wrong answer before the subject of the experiment answered.

The result: about a third of the time subjects went along with the majority view, though it was clearly wrong. The painful lesson: we are social creatures, swayed by the group, even willing to sacrifice the truth just to fit in.

Locked in the echo chamber

Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites can reinforce all the above instincts through creating “echo chambers” that validate what we chose to believe.

Exposure to different ideas does not fit well with the economics of online media – in which platforms, and content creators on those platforms, fight for limited attention by appealing to preferences and prejudices.

We enjoy echo chambers.

According to psychologist Jonathan Haidt, we appear to be born with a “self-righteousness gene” – an inherent need to be right. We are more prone to defend our opinions by criticising others. We find comfort in validation.

Once we have made our opinion known to others, we are doggedly reluctant to change course. Seeming consistent can become more important than seeming right, so we will go to great lengths to shore up opinions that come under scrutiny.

These foibles might be endearing if they didn’t have such serious implications. Believing in misinformation is an undeniable problem.

But we are going to need a different way to deal with conspiracy theories than simply trying to ban them. Seeking to enforce a single accepted narrative is not the solution.

If Facebook or mainstream media are the arbiters of who gets heard and who does not, then we will be pushed more towards our own filter bubbles, and conspiracy theorists towards theirs.

Meg Elkins, Senior Lecturer with School of Economics, Finance and Marketing and Behavioural Business Lab Member, RMIT University and Robert Hoffmann, Professor of Economics and Chair of Behavioural Business Lab, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more from The Conversation: