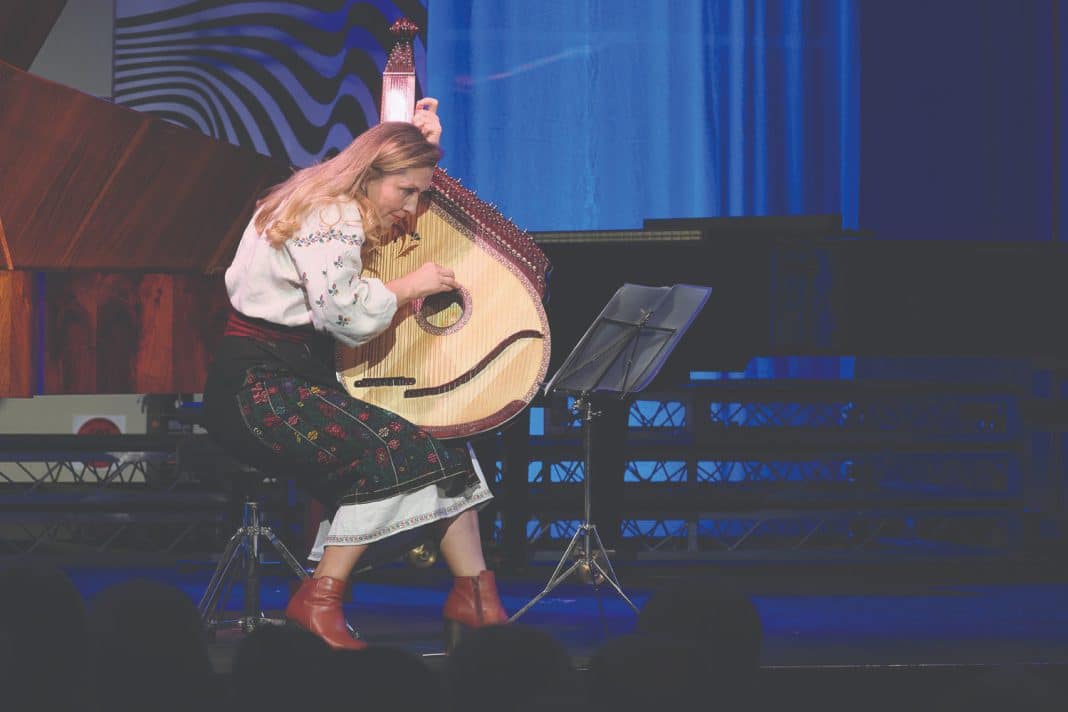

Ukrainian musician Larissa Kovalchuk performs to draw attention to her people’s plight. The soprano and player of the bandura, the traditional Ukrainian stringed instrument, will be the star of a fundraising concert for her country at Llewellyn Hall on Tuesday 31 May.

“It’s frustrating for me to be here, knowing what’s going on in my country,” Ms Kovalchuk said. “Sometimes I feel guilty that I’m in a safe place… [But] I feel that this is my duty and my purpose right now.

“I can bring awareness to people. People get used to the war happening; even people in Ukraine adapt to this horrible situation. But we have to remind humanity it shouldn’t be like that.”

Music for the People of Ukraine, a collaboration between the Canberra International Music Festival, Canberra Symphony Orchestra, and the ANU’s School of Music, will raise money for the Australian Red Cross Ukraine Crisis Appeal and Médecins Sans Frontières.

The concert will feature Ukrainian folk music and works by Ukraine’s most famous living composer, Valentin Silvestrov.

Homeland and country are the theme of arias Ms Kovalchuk will sing from Hulak-Artemovsky’s opera Zaporizhets za Dunayem (A Cossack Beyond the Danube, or Cossacks in Exile).

She will also sing Ukrainian composer Myroslav Skoryk’s “very, very sad and pretty” Melody, a wordless a cappella piece originally written for the flute, as well as a couple of songs based on traditional Ukrainian folk music.

The ANU Chamber Choir will sing Plyve kacha, a Ukrainian folk song about a son going off to war, parting from his mother. The four-part harmony is beautiful, Ms Kovalchuk says.

She will also perform the bandura, “the voice of the Ukrainian nation from generation to generation”.

Dating back to the sixth century, it was once a sacred instrument that only men could play, singing historic and heroic epic ballads, descriptions of nature and the seasons, or uplifting stories about family and social values. From the 19th century, Russia tried to suppress the instrument: the Tsarists banned performances, while the Soviets exiled or murdered bandurists, culminating in a massacre in Kharkiv in the 1930s. Many fled to Canada and the USA.

Restrictions were eased after Stalin’s death, but those bandurists still in Soviet-occupied Ukraine had to sing Communist works; works with nationalist or religious elements were banned. Few men were allowed to study or play the instrument professionally.

Ms Kovalchuk herself studied voice, bandura, and conducting at the Kyiv Conservatorium of Music, and became one of Ukraine’s leading bandura players, performing in Western Europe, and earning international renown at a 1993 festival organised by Yehudi Menuhin.

But as a student before the fall of the USSR, because she played a traditional national instrument, she had to be careful what songs she sang. Her teacher warned her that if she wanted to graduate from the Conservatorium, she should not attend meetings and demonstrations, or sing too many Ukrainian nationalistic songs.

Similarly, when she and fellow Ukrainian students performed in Germany or France, KGB agents accompanied them on tour to check who they talked to, what they said, and where they shopped.

Since moving to Australia in 1996, Ms Kovalchuk has recorded for SBS and the ABC, and appeared at the Sydney Opera House, numerous multicultural and folk festivals, and in concerts for Musica Viva and the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra.

Now, she watches what is happening in her home country with great concern.

Three months ago this week, on 24 February, Russia invaded Ukraine. Somewhere between 10,000 and 25,000 civilians have been killed, according to the Ukrainian government. (The UN figure is lower: nearly 4,000 killed and 4,500 wounded.)

In the worst refugee and humanitarian crisis since the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, more than 6.4 million Ukrainians have left their country, 90 per cent of them women and children, and a quarter of the population been displaced.

“I am trying to help as much as I can,” Ms Kovalchuk said.

She and her partner send clothes and medical assistance to people she knows and to the army, including her partner’s nephew. “They are defending the country,” Ms Kovalchuk said.

She speaks of relatives hiding under their building, of bombs and broken windows, and of friends escaping to Poland, but returning to look after elderly parents.

Ms Kovalchuk recounts a litany of horrors in this “ugly and inhuman” war: mass graves, parents and children murdered, women raped in crowds, simple civilians shot through the head.

“Russian savages – you can’t call them any better name. I’m very upset and very angry.

“How can humans do something like that to other humans? We used to be ‘brothers’; they called us ‘brothers’ all the time.”

But the current invasion is only one chapter in the “long history of the suppression and repression of the Ukrainian nation”, Ms Kovalchuk says; the Russians have long tried to dilute the nation and wipe Ukraine from the face of the earth.

Her own family was caught up in Operation Visla (1947), a Soviet attempt at ethnic cleansing when 150,000 Ukrainians living in Poland were relocated to what is now Ukraine. Many died, or were “put on trains and left in the middle of nowhere in winter”. According to the Kyiv Post, resettlement directives decreed that “no more than a 10 per cent concentration of Ukrainians could constitute the population of any urban or rural location”.

Her father’s family was displaced from Sanok (now in Poland), in the Carpathian Mountains, and taken to western Ukraine, left at night with five children.

“They had to start from zero, and settle, work, and build their own house,” Ms Kovalchuk recalled.

Again, many Ukrainians were sent to Siberia: “Tortured, murdered, without knowing what they did wrong,” she said.

Ukraine survived the Soviets, and declared its independence in 1991; with the support of the free world, Ukraine could resist the current Russian invasion.

Australians, Ms Kovalchuk said, have been “very helpful and sympathetic”. The former Coalition government provided more than $65 million in humanitarian assistance, a $21 million support package of defensive military assistance for Ukrainian armed forces, and 20 Bushmaster armoured vehicles.

Strangers have given Ms Kovalchuk money to send to Ukraine; she has received many invitations to perform; and she was touched by her students dressing in blue and yellow, Ukraine’s national colours.

“I hope when all this horror is finished, I will be able to visit my country again… I’d like my children to see my country again.”

The concert also features William Barton, Miroslav Bukovsky and Friends, Kim Cunio, Andrew Goodwin, the CSO Chamber Ensemble and the ANU Orchestra, with Roland Peelman and Max McBride conducting.

Music for the People of Ukraine, Tuesday 31 May 7pm; tickets $55–$75. Book online at cso.org.au/event/music-for-ukraine or call CSO Direct on 6262 6772 (weekdays, 10am–3pm). Tickets will also be available at the door (unless sold out sooner).