Across Australia on Wednesday night, millions of people watched the Australian of the Year awards, celebrating the achievements of some of the most inspiring people in the country: the likes of Taryn Brumfitt or Professor Tom Calma, the second consecutive Senior Australian from the ACT.

For Canberra artist Cathy Newton, the event is the culmination of months of hard work. She makes the awards themselves: she crafts and polishes those elegant yet solid geometric forms of blue glass at the ANU School of Art and Design’s Glass Workshop, where she is technical officer.

“I am humbled that the workmanship that goes into making these awards is recognised,” Ms Newton says. “There are many skills and excellence of working ethic involved to maintain the high standard of presentation and design.”

It takes her 10 hours to make each of the 32 awards: eight Australians of the Year, eight Senior Australians, eight Young Australians, and eight Local Heroes. She starts working on them in June, delivers the regional awards in October, and the major awards a fortnight before Australia Day. And the whole nation sees her work.

“This award is the most viewed piece of glass that comes out of this workshop,” Dr Jeffrey Sarmiento, head of the workshop, says.

“It’s known to everyone who watches it on telly. If you think about all the recipients of that award, how distinguished they are within their individual fields, just imagine the number of people who are seeing it. It’s quite a big deal for it to be made here, and by us.”

- Body image teacher Taryn Brumfitt named 2023 Australian of the Year (25 January)

- ACT’s Tom Calma named Senior Australian of the Year for 2023 (25 January)

- Over 50 ACT residents recognised in 2023 Australia Day honours (25 January)

The ANU has made all the Australia Day awards since 2018. In 2017, the ANU negotiated a sponsorship agreement with the Australia Day Council to make the awards and provide the music at the awards ceremony.

The original awards were designed by Richard Whiteley, the former head of the glass workshop, and two other academics at the school. The design has changed slightly since; the current award is the third iteration, Ms Newton says.

The award depicts the Southern Cross and the seven points of the Federation star; the blue represents the Australian sky; and the different facets symbolise the multicultural, multifaceted elements of society, “embodying a nation,” the ANU states, “that is confident in its leadership, contemporary in its outlook, and distinguished by its diverse community”.

“So much handiwork and craftsmanship is embedded in these objects,” Dr Sarmiento says. “They look like they weren’t even made. The refinement is so high they look like they emerged from nothing.”

Each category has a different coloured corner: red for the Australian of the Year, green for Senior Australians, yellow for Young Australians, and blue for Local Heroes.

“Not one award is the same,” Ms Newton says. “They have a similar shape, but the way the colour bleeds is quite different.”

Before the pandemic, Glass Workshop students helped to make the awards. It was, Ms Newton says, great for their skills: they learnt how to polish, flatten, shape, and fire glass, how to work with different temperatures, and how to make refractory moulds.

“That only stopped once COVID hit,” Ms Newton says. “The awards still went on, but we didn’t have any students on the ground.”

Ms Newton took over the making: she had worked on the first ones in 2017; now, she makes them all.

This year, however, students will be involved once more. The workshop has rebooted its internship program, and will assign students to the project.

True blue

Glass is made using silica sand, flux, and ash. This is the first year the Australia Day awards are made using Australian glass – in the past, the glass was sourced from New Zealand. (Forget disputes over pavlova or lamingtons; that’s enough to make jingoists foam at the mouth.)

But henceforward, the awards will be made with glass supplied by James Thompson in Victoria’s Rubicon Valley.

That lake crystal glass, containing 40 per cent lead, is clearer than normal glass, Ms Newton says.

The blue hue is achieved using rare earth colourants, Dr Sarmiento explains. In the ancient past, simple chemical oxides such as cobalt or gold were used to vary the colour of glass to blue or pink.

Microscopic amounts – “crazy low amounts,” Ms Newton says – of colourants are needed: 0.8 or 0.08 grams.

“Drug weight scale!” Dr Sarmiento says.

But the artists have to be careful: if too much cobalt is put in, the furnace will stay blue forever.

Below: Dr Jeffrey Sarmiento, head of the glass workshop, demonstrates glass blowing. Photo: Kerrie Brewer

Making the awards

Most of us picture glassblowers as Venetian artisans blowing molten bubbles – but the awards use cold glass.

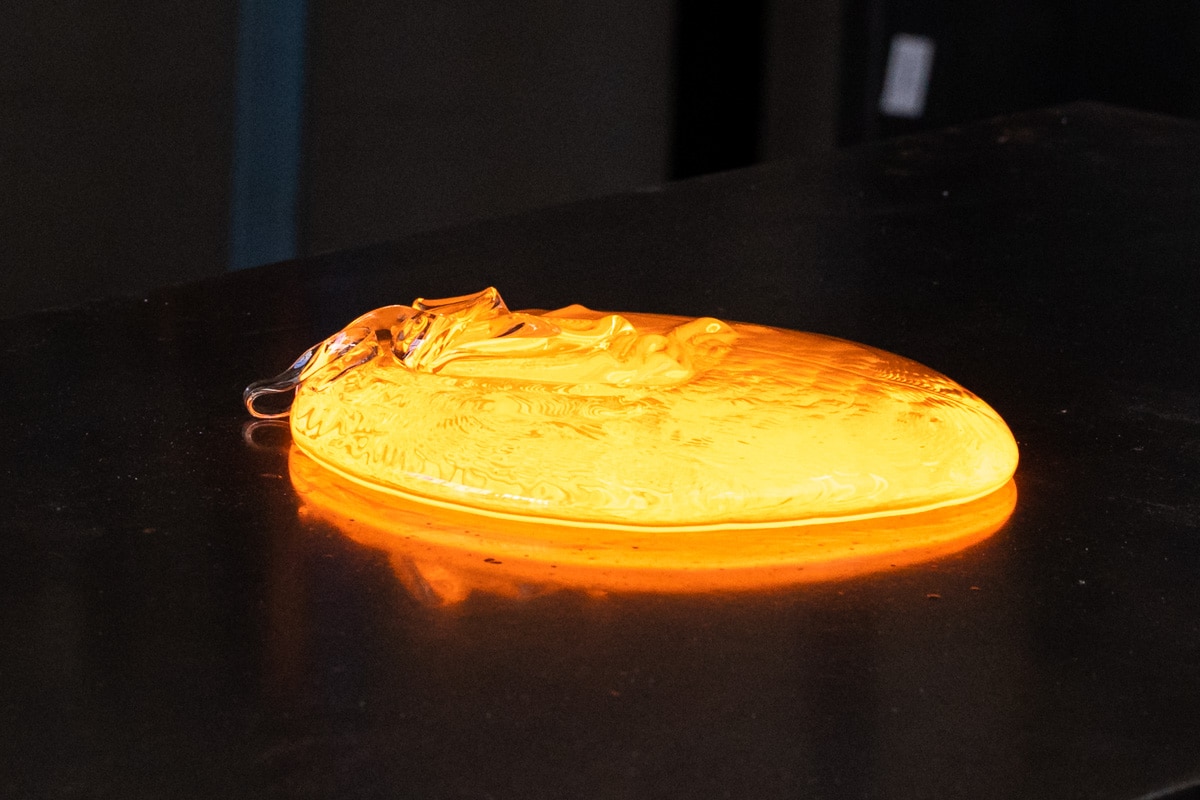

A viscous chunk of glass is poured from the furnace, and cools on a marver (a metal heat sink) to becomes a solid disc of glass. That disc is hit with a hammer, and smashed into smaller pieces.

Below: Dr Jeffrey Sarmiento pours molten glass onto a marver. Photo: Kerrie Brewer

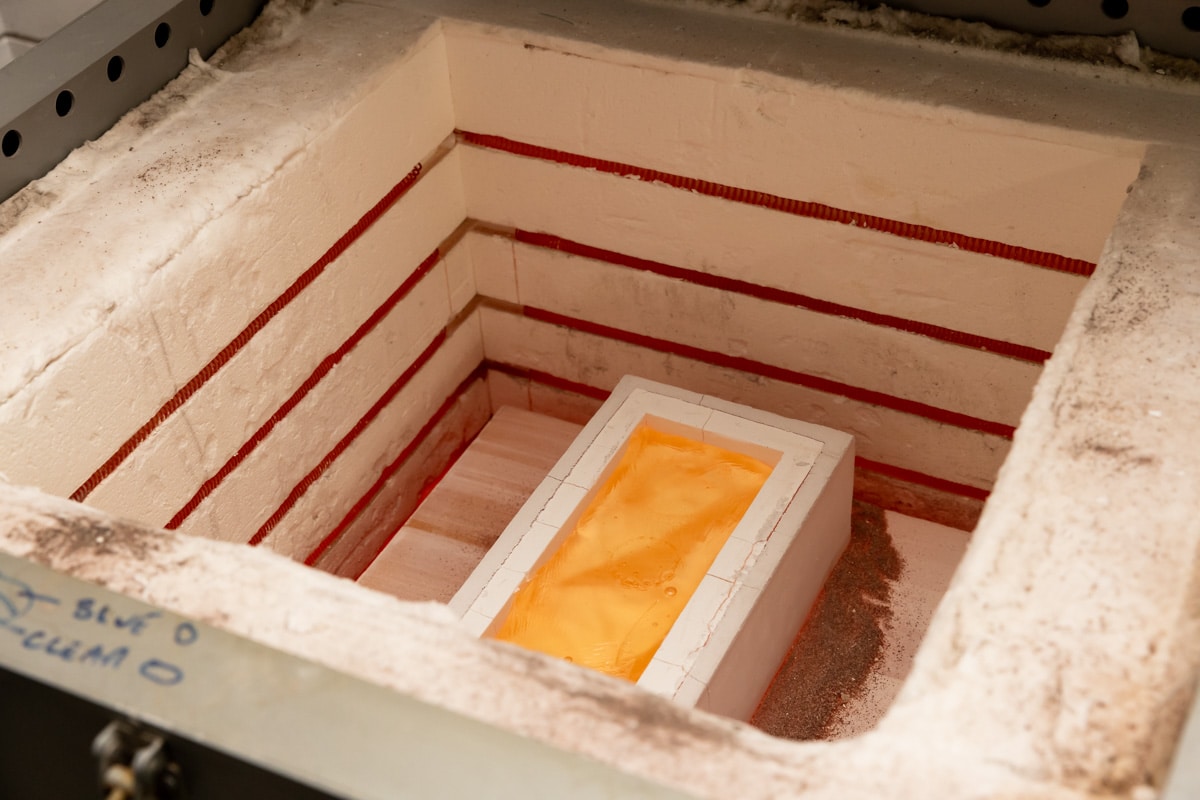

Ms Newton puts the cold glass into a refractory mould (in the shape of the negative of the award), and fires it in the kiln, which is heated to more than 800oC.

The award stays in the kiln for a week: while it is only fired at 830oC for five hours, it must cool down slowly. Otherwise, it could suffer annealing stress and fall apart, Ms Newton explains – like when a warm glass is taken out of the dishwasher, filled with iced water, and shatters.

When the award comes out of the kiln, its sides need to be straightened and the back flattened. Ms Newton polishes the award on a flatbed. She pours silicon carbide grit (an abrasive) on the flatbed, then grinds the base off until the award is flat.

Ms Newton then uses a diamond blade angle grinder to polish the award completely smooth.

The recipient’s name still needs to be added. Ian Broadbent, of Capital Trophies, Mitchell, is the final port of call: he sandblasts the names onto the award, and puts the design on the back.

Ms Newton then adds the finishing touches: she sprays the award and puts the bases on. The bases are electroplated with ink, while the stands are boxes made in Adelaide.

Job done, until next year.

She makes backups in case something unexpected happens, an award gets dropped, or a spelling error is made.

In the last couple of years, Queensland siblings and spouses were jointly named the Young (2021) and Regional (2022) Australians of the Year. Those Christmases were “a mad panic”, Ms Newton remembers. She is relieved there were no doubles this year.

Once, too, she had to remake an award for a Senior Australian of the Year, whose excited grandson had broken it.

But glass’s incredible fragility appeals to artists, Dr Sarmiento explains.

“It’s risky and takes real discipline to understand what the glass is doing – which, I think, is why working in the crafts is really important. People need to know how to work with their hands.”

And the ANU Glass Workshop is one of the best places to learn. Dr Sarmiento, Chicago-born, was appointed head of glass two years ago, but wanted to work here for 25 years.

“This is one of the world’s great glass workshops,” he says. “It’s internationally famous. Glass artists come out of this glass workshop who have a huge international impact.”

But he reflects: “It’s visible on an international scale, possibly not locally.”

With Cathy Newton’s work broadcast into every Australian living-room, that is certain to change.