Although a familiar name to Canberra political insiders, Van Jones is generally not well known in Australia. He was the green jobs czar in the Obama administration and has made the easy transition to being a CNN host, where he campaigns for Kamala Harris. During a discussion on green energy, he made a remarkable admission, saying, “Early on in my career, we thought we were going to be able to get all the way to our clean energy goals with no fossil fuels. It turned out that wasn’t true.”

Contrary to the view expressed by Anthony Albanese and Chris Bowen, Van Jones is now toning down the renewable goals that have featured so prominently in the US with subsidies under Build Back Better, as is the case with our own Future Made in Australia.

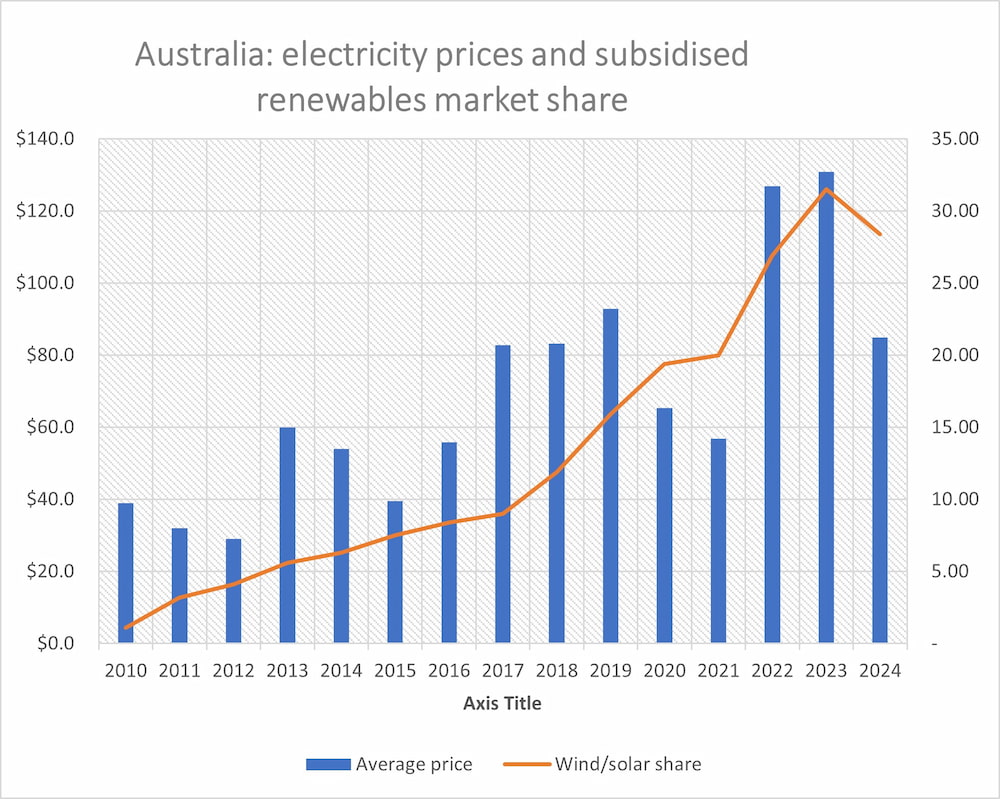

Australia has actually travelled further along the path of forcing renewables into the electricity system than the US and all but a few EU countries. The $30-40 per MWh price prevailing in Australia when renewables were under five per cent of the market has escalated to over $130 per MWh as the forced injection of renewables increased to over 30 per cent.

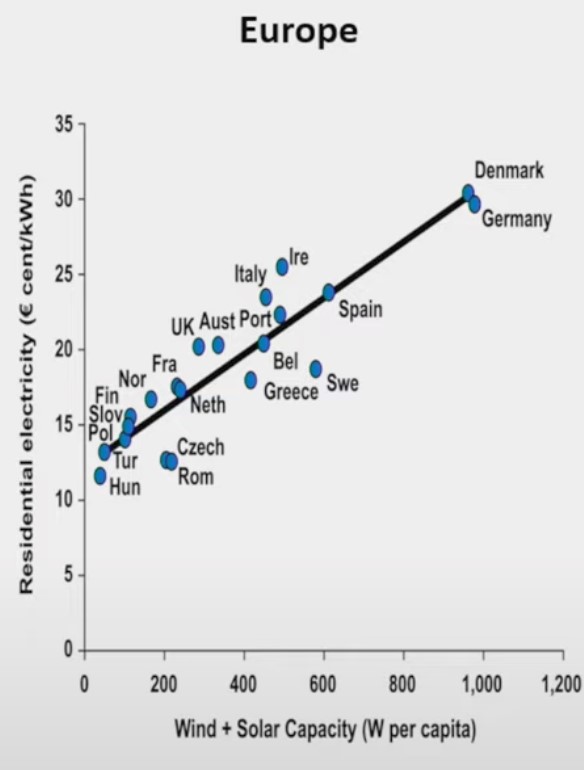

The same pattern is evident across countries. There is a strong correlation between prices and the per capita consumption of wind and solar. The nations in Europe with the highest solar and wind capacity (Denmark and Germany) have the highest prices while those with the lowest wind/solar capacity (Hungary, Poland and Turkey) also have the lowest prices.

Coal is far and away the cheapest source of energy for Australia. However, we have embarked on eliminating it from the system due to a combination of spurious fears about it causing global warming and unfounded optimism in a wind/solar system.

Had we not followed this course, we would have been progressively bulding new capacity, as we did 20 years ago. Today, we would not be facing the loss of the aluminium smelting industry former jewel in the nation’s industrial crown. Indeed, our low-cost energy would see metal smelting in general expanding and an absence of the vast expansion of land intensive bird-killing and visually intrusive wind and solar and their associated need for more transmission lines.

The propaganda against coal is preventing the Opposition from embracing this energy source at the present time. Mr Dutton is instead opting for a nuclear-powered energy future.

Mr Bowen has put the cost at $387 billion for one Peter Dutton option that would require 71 small modular reactors, each producing 300 megawatts. Others put the cost of nuclear at one third of this. Thus, four recent nuclear installations in the United Arab Republic (UAR) each with 1,400 Megawatts 24/7 capacity and with an 80-year life cost $9.5 billion a piece. At that cost the 21,000 MW of capacity to which Mr Bowen was referring would cost little more than $100 billion.

Under the present government policy Australia spends some $16 billion a year in subsidies to renewables and, as the renewable facilities will only last 15 -20 years, that cost will be incurred forever. Coincidentally $16 billion a year comes to $380 billion between now and 2050, the same cost as Mr Bowen puts on the Dutton nuclear plan.

But the difference is that the Bowen plan will give us a highly unreliable network.

One solution is to massively overbuild wind/solar power and store the surplus in batteries. A difficulty in this is that additional supply decreases with each increment of intermittent capacity – in low wind or low sun periods it is just very difficult to climb from the “normal” 26 per cent no matter how many turbines are present.

An alternative is to embark on a vast additional set of spendings on storage in the form of batteries and Snowy 2 type hydro pumped storage. But even with highly optimistic assumptions, Paul McArdle of Global Roam (not an opponent of the “transition” to renewables) came to an estimate of 9,600,000 megawatt hours. The US National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates storage costs by 2030 to be $US200,000 per megawatt hour. This cost means reliability-proofing Australia’s network at an outlay of $6 trillion, three times the nation’s GNP. This is an expense that is not required for coal, gas or indeed, nuclear.

What we see across the world is two contrasting economic management models – that of the Euro-US-Australia world, and that of the Asian countries, principally China and India.

The Western world seeks to force a substitution of wind and solar for the fossil and nuclear fuels that have powered economic development. The Asian countries’ focus is on growth underpinned by using the proven energy sources: coal, gas, and nuclear.

Thus, since 2020, China and India have added 1,588 GW of coal capacity compared to only 63 GW in the rest of the world (with only Poland building significant new supply in the EU-UK-US and Australasia Western nations). With nuclear, China, Russia, and India have 36 new plants underway. The rest of the world has 23 with only 4 in the UK-EU-US.

The Asian nations are enjoying much faster growth and industry is gravitating towards the lower cost energy their strategy is founded upon.

A Trump victory would steer the US in that direction, while, as the remarks by Van Jones indicates, even a Harris victory is likely to see some tempering of the current headlong dash away from coal and gas that has been the US approach under Biden.

Australia could join the success evidenced in the Asian economies. This would be especially the case if we were to revert to a coal-based system in which we enjoy tremendous advantages in low-polluting coal that is inexpensive to mine and feed into power stations. Even with the second-best alternative of nuclear, as long as we adopt the sensible regulatory practices that are in place in India, China, the UAR and elsewhere, we could avoid the deindustrialisation that is presently occurring.

Editor’s note: Dr Alan Moran was the Director of the Deregulation Unit at the Institute of Public Affairs from 1996 until 2014 and was previously a senior official in Australia’s Productivity Commission and Director of the Commonwealth’s Office of Regulation Review. He played a leading role in the development of energy policy and competition policy review as the Deputy Secretary (Energy) in the Victorian Government.