Researchers at UNSW have found an interesting discovery while studying humpback whale airway mucus … or snot.

Collecting samples of whale blow showed the sea-creatures to be in significantly poorer health on the tail end (pun intended) of their southern migration season, where they travel 8,000 kilometres and fast for most of the journey.

East Australian humpback whales travel between Queensland and Antarctica from May to November each year, known to most as whale-watching season.

Study lead author and UNSW Science researcher Dr Catharina Vendl said the research was paving the way in studying the mammal’s overall health in the least invasive way.

“The physical strains of the humpback’s migration likely affected the microbial communities in the whales’ airways – so, our findings are key to further developing the analysis of airway microbiota as a non-invasive method for monitoring the immune function and overall health of whales and dolphins,” she said.

“People enjoy whale-watching season, but with it comes reports of whales becoming stranded. Although humpback whale stranding events occur naturally and regularly to injured and young whales, it is crucial to monitor the population health of this iconic species to ensure its long-term survival.”

Dr Vendl collected airway mucus from 20 humpback wales in Hervey Bay, Queensland, during the humpback’s return leg to Antarctica in August 2017 when the whales were several months into their migration.

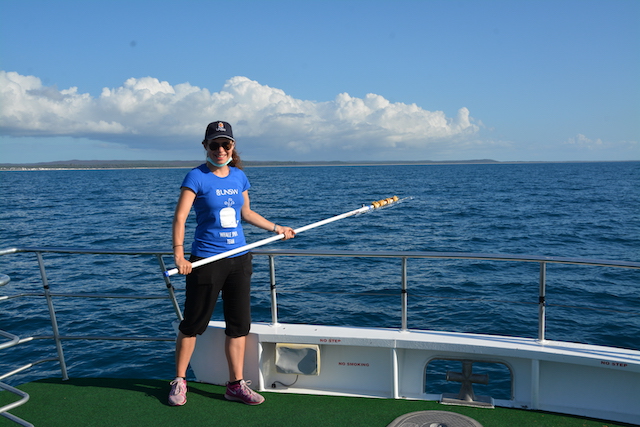

RIGHT: A waterproof drone which Dr Vendl used to collect samples of whales’ blow in Hervey Bay in 2017. Photo: Jess Dargan.

The samples were compared to mucus taken by Macquarie University researchers in May and June, at the beginning of the migration season of the same year.

Dr Vendl said she believed the creatures fasting during migration was a major contributing factor into the decline in health.

“Humpback whales mostly live on tiny creatures called krill, but because there is less of this preferred food along the east Australian coast and it’s such a huge effort for them to open their mouths to feed, they rely on energy stored in their blubber,” she said.

“Fasting is therefore a major physiological strain during the whales’ migration.”

The east and west Australian humpback whale population had almost been hunted to extinction, with the last whaling station closing in Byron Bay during 1962.

They are now listed as a vulnerable species under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

“Humpback whales do not only play an essential role in their marine ecosystem but also represent an important economic resource, because whale watching is a booming industry in many Australian cities and around the world,” Dr Vendl said.

“So, these whale populations are not endangered, but that doesn’t necessarily mean things will stay that way.”

Find the study in Scientific Reports: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69602-x

View the Australian Academy of Science video about the study: https://vimeo.com/435003703/4222edc479