Some of us crave caffeine in the morning, some crave a beer at the end of the day, others crave intimacy with another person – we all crave a sense of connection. Take a voyeuristic journey of connection and intimacy between a community of lovers and friends in Nan Goldin: The ballad of sexual dependency, at the National Gallery of Australia until 28 January 2024.

Through deeply personal and vulnerable portraiture, Nan Goldin wanted to use her art as a way to keep her loved ones with her in her memory. Her career and genre-defining work, The ballad of sexual dependency, tells the story of Goldin’s chosen family, their partying highs, addicted lows, and the relationships that guided them in just 126 photographs.

Like many great artists, Goldin’s life was shaped by tragedy; her older sister took her own life when Goldin was just 13. Rather than address the issues, her family responds by sweeping it under the rug. Goldin leaves the family home in fear of the same thing happening to her, going on to live in a foster home.

At 15 years old, Goldin enters a radical community school that will shape the rest of her life. Here, she meets her tribe, including David Armstrong and Suzanne Fletcher, and gets her hands on a Polaroid camera.

“Nan realises that this is going to be the means by which she is going to negotiate her life. It’s the way she’s going to be able to build community with other people … That historical photojournalist way of photographing people that you don’t really know is no interest to her at all,” says Anne O’Hehir, NGA Curator of Photography.

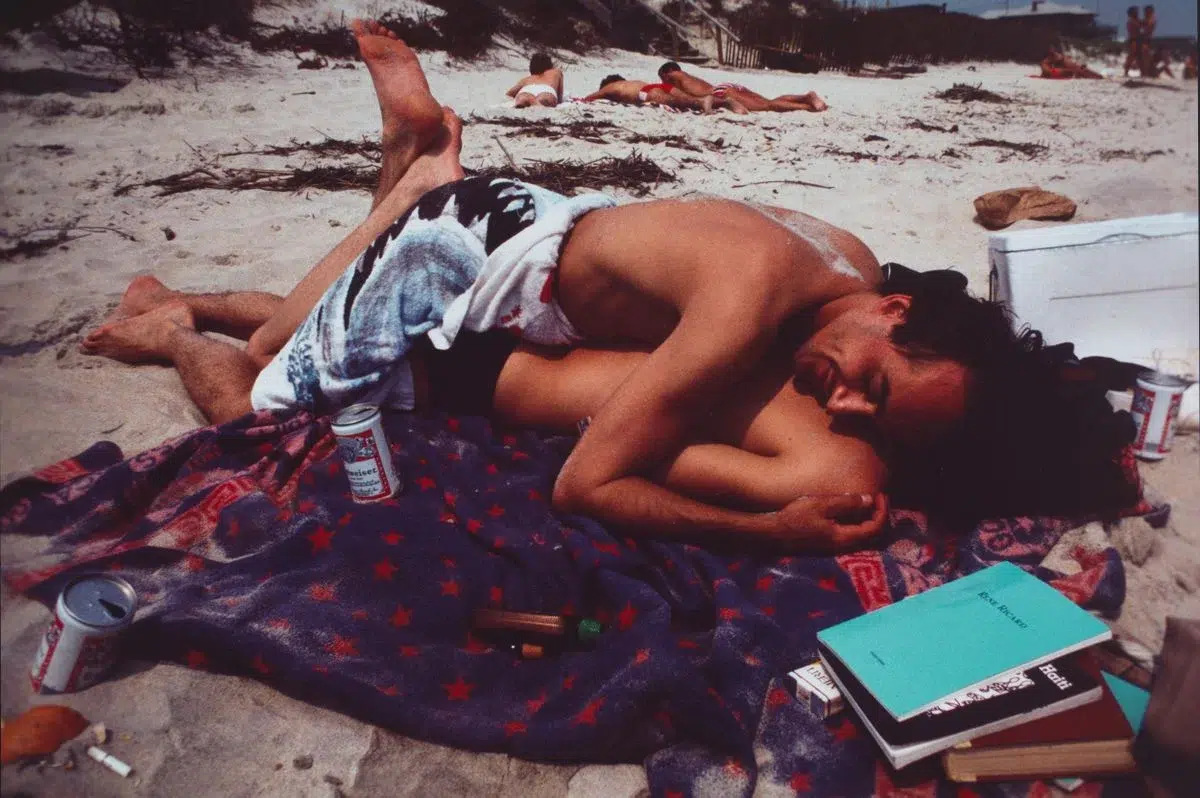

Heading to New York in 1978, it only takes a couple of weeks for Goldin to find her place and be welcomed by her community of artists, makers and those in the LGBTQIA+ scene. Taking photographs of their times together, Goldin sees them as stars in the films of their own lives. The way the snapshots are taken transports the viewer to the party, beach or bedroom and introduces them to the subjects.

“She uses the camera in a way that is like an extension of her body; she always has the camera with her, the way the series builds you keep on running into the same people,” says O’Hehir.

Behind the ballad

One of the subjects throughout the ballad is Cookie Mueller, an actress with a cult following who starred in a number of John Waters films; she is seen dating a woman named Sharon. Goldin follows relationships throughout the body of work; it sees Cookie’s marriage with Vittorio Scarpati before both of them succumb to AIDs-related illnesses.

“She [Cookie] is in this lesbian relationship, she breaks up with Sharon, and about five minutes later goes to Italy to get herself together with Vittorio … I love those little in-gossipy stories that are part of the ballad that we sort of can get,” says O’Hehir.

One of the things that made the work influential at the time and remain relevant today is the way it captures friendships and a sense of community. Intimate portraiture was reserved for men capturing their partners and Goldin broke that stereotype, explains O’Hehir.

“That thing of friendship; how you negotiate those difficult relationships between men and women is really through the power and support that you get from your friends. I think it’s a radical thing to say at the time, we’re still 1970s, 1980s America.”

By the time Goldin’s now famous work comes out in the mid 1980s, New York is in the depths of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and this community she photographed is being decimated.

“In ’86, I read somewhere that over 2,500 people in New York alone are dying, so all these people are dying and Cookie is dead by ’89,” O’Hehir says.

The loss of her older sister, Barbara, follows Goldin. Unable to remember what Barbara looked like, she wanted to ensure that she photographed those she loves as memory and proof they existed.

Goldin and her friends were aware of themselves in the centre of their own world but also how others may see them, explains O’Hehir. She says they wanted to break down the misconception that her community was the ‘other’; Goldin’s exhibitions at the time were a form of activism saying, ‘we are here, we’re not leaving, and you need to respect us’.

“It’s a simple message but also a really powerful one, particularly at a time when the headlines in ’86 were like ‘gays kills babies’. This community is being enormously vilified and made to vanish,” O’Hehir says.

The raw and intimate portrayal of life contains explicit images depicting nudity, sexual acts, drug use, and the impacts of violence against women. It is not for audiences under the age of 15, with some images capturing people in moments of passion with a partner or self-love. O’Hehir says it is evidence of the immense trust these people had in her.

“She’s like ‘I want you to see yourself as beautiful as I see you.’ There’s a huge act of generosity in the way that Nan, very warm-eyed, approaches it. As honest as she can but she really wants it to be an honouring of these people’s lives.”

See the genre-defining works in Nan Goldin: The ballad of sexual dependency at the National Gallery of Australia until 28 January; nga.gov.au

Canberra Daily is keen to hear from you about a story idea in the Canberra and surrounding region. Click here to submit a news tip.